The list of artists is organized alphabetically

© of the works, the artists

Pablo Accinelli

Donde quieras que estés, 2010

Col. Oxenford

In Wherever You May Be (2010), Accinelli transforms a phrase addressed to an “other” —intimate, uncertain, or absent— into an installation that strains the boundaries between public language and the encrypted message. Each letter of the message is printed on paper rolls of different sizes, grouped together with elastic bands that keep the structure standing. Despite the fragility of the material, a minimal force holds it in place.

As they read while moving, viewers recompose the phrase that gives the work its title: one can decipher what it says, but never know who its intended recipient is. Pablo Accinelli explores the relationship between use, form, and language to examine how objects organize perception and everyday movements. Using simple materials, he constructs works in which the functional shifts toward the conceptual: the objects appear suspended, paused, or under tension, as if they were part of a system operating on the edge of balance. This subtle variation on the everyday proposes an experience in which the familiar is perceived in a different way.

Nicanor Aráoz

S/t, 2011

Col. Oxenford

His work centers on sculptures, drawings, and installations, drawing on references from anime, Internet imagery, and the romantic mythologies of gothic art. He incorporates surrealist procedures—such as the juxtaposition of dissimilar objects and the oneiric—which in his pieces take on frenetic forms, akin to nightmares where pleasure and pain seem to merge.

In this early piece, Aráoz introduces the human figure for the first time through direct body casting, marking a shift from the mannequin and the found object toward a more immediate relationship with the real. The artist explains that he was searching for “something of the real,” and that this process left visible marks: deformities in the mold, open seams, and the contortion of the emerging figure.

Aráoz views this work as the beginning of his sculptural language and the acceptance of error as part of the process. His readings also permeate the piece, especially Breton’s black-humor texts and Acéphale, the magazine by Bataille and Masson, whose focus lies on nocturnal rituals. The sculpture condenses that imaginary into a headless, visceral, and tense form; the chain surrounding it reinforces the ambiguity between punishment, concentrated energy, and suspension, while the circular saw heightens the theatrical dimension of the ensemble.

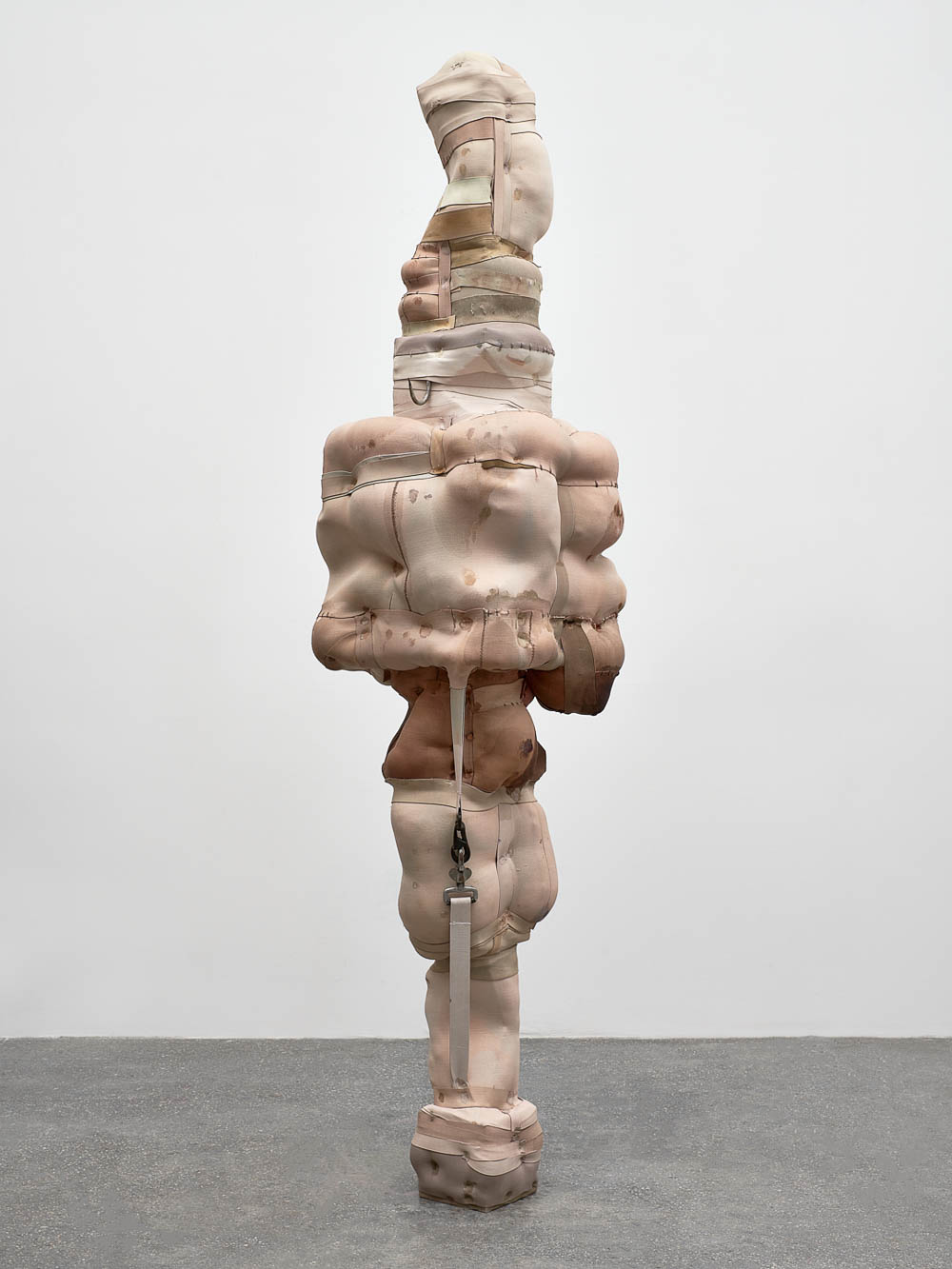

Patricia Ayres

14-5-18-5-21-19, 2023

Col.Balanz

In Patricia Ayres’s work, structures of social conditioning—particularly catholic morality, incarceration systems, and stereotypes surrounding the body—function as central conceptual cores. Influenced by her background in fashion, Ayres creates sculptures wrapped in meters of elastic that give rise to imposing yet fragile corporeal forms, traversed by the symbolic resonances of their materials. In this sense, the artist reflects: “Elastic is used in fashion, but also in medical and military contexts; its use evokes ideas of wounding, repair, and control.” Many of her pieces appear “tied” with harnesses, pierced with butcher hooks, and assembled with parachute hardware, then dyed with anointing oil, sacramental wine, iodine, ink, and what the artist describes as gunk.

In 14-5-18-5-21-19, her interest in generating an image of the vulnerability of the body subjected to power becomes especially clear. The numerical title functions as a coded nomenclature that, recurrently, refers to the history of saints. Through distorted forms, the artist constructs an anthropomorphic figure that is wrapped and sutured: a body marked by wounds, injuries, and other forms of human domination.

Andrés Bedoya

Vestimenta II, 2016

Col.Balanz

Andrés Bedoya develops a practice that reflects on notions of purity and binarism, exploring the complex network of rituals, beliefs, and objects that have shaped—and continue to shape—Andean history and his own experience. In dialogue with the questions he poses about identity, territory, icons, and regional history, he conceives materiality as a device capable of activating both personal memory and communal past.

Vestimenta II is a central work within this investigation: it juxtaposes sewn fabric—symbol of the intimate, the malleable, and the handmade—with metal sheeting, a material associated with industrial hardness, military protection, and mining in the region. This intersection between fragility and armor results in a suspended, mysterious, undefined fragment of clothing. Through this gesture, Bedoya gives the object a critical dimension and reveals the tensions of a body marked by historical processes.

In the artist’s words, this complex integration is essential to his vision: “I have no interest in the purity of anything. […] The universal does not have to exclude the local. The work is not about mining but about something much broader. I am speaking about an instance that has shaped the region’s history.”

Diego Bianchi

S/t, 2005-2011

Col. Oxenford

Anabolismo, 2015

Col. Cherñajovsky

Caleidoscopio, 2016

Col. Cherñajovsky

Lying Down Muscled, 2024

Col. Cherñajovsky

Diego Bianchi’s practice operates as an open testing ground in which material and spatial experimentation functions both as method and mode of thought. His projects create immersive environments that require an active viewer capable of navigating multiple systems of reading, placing his work in a territory where the functional, the residual, and the vital are constantly redefined.

Under this working logic, Bianchi was invited to design the exhibition space for his own works and those of other artists, combining artistic practice with a curatorial dimension. Using discarded objects and consumer materials, he presents sculptures that question the excesses of the contemporary world.

His pieces trace a genealogy of investigations into the body as a network of connections where things and bodies devour one another. This approach appears in Untitled (2005–2011), featuring wood fragments and women’s shoes fused with epoxy putty, and intensifies in Anabolism (2015), a dense conglomerate of iron, plastic, and optics that suggests a failed organism built from modern debris. In Kaleidoscope (2016), iron, mirrors, video, and televisions create an immersive space that fragments reality and challenges perception.

His most recent work, Lying Down Muscled, condenses these concerns: a fuel tank coated with epoxy clay supports muscled mannequin fragments assembled with a wheelchair, exposing bodily fragility, prosthesis, and dependence on machinery as elements of an exhausted system.

Federico Cantini

Zarpada, 2025

Col. Cherñajovsky

Federico Cantini’s sculptural practice focuses on an intense object-oriented animism, where materials become universes imbued with diverse sensitivities. His works—whether wood carvings or clay reliefs—explore the intimate relationship between the hardest physicality and the most vulnerable human processes.

Cantini establishes a fundamental tension in his methodology: he employs the force of tools like axes and hammers to work with residual pruning wood, while the final result coexists with the softness of the hand’s gestures. This process shapes presences that can be understood as traces of emotional states, bodies in expansion, or dramatic episodes drawn from urban life.

In Zarpada, the artist uses cypress wood—a material associated with nobility and permanence—to inscribe a figure or event that exceeds its limits. The title, with its Argentine colloquial resonance evoking excess, wildness, or prominence, serves as a key to interpreting the piece. The work evokes scenes full of ambiguity, drama, and disorder, materializing the raw, overflowing energy of human experience.

Paula Castro

No me siento bien (o Skinny Bitch), 2018-2023

Col. Oxenford

Over the past decade, Paula Castro has explored various object-based and sculptural forms, combining drawing, conceptual procedures, and humor. Her work focuses on the appropriation, deformation, and material experimentation of everyday objects to reveal what their functionality usually conceals.

No me siento bien (or Skinny Bitch) exemplifies this approach: starting with the plastic Monobloc chair, the artist sands it down until it loses its function, transforming it into a fragile skeleton that still retains traces of its original identity. The result oscillates between the comic and the unsettling, critiquing consumerism while revealing a minimal, essential form. As curator Carla Barbero notes, the sculptures embody “the spirit of impoverished communities, who preserve in their imagination and cunning a vital mystery.”

Eduardo Costa

Cuña blanca con objeto genitivo, 2009-2011

Col. Cherñajovsky

Eduardo Costa is a key figure in conceptual art in Argentina. His series Voluminous Paintings or Solid Acrylic Objects represents the culmination of his project to subvert the tradition of painting in its two-dimensional format and as a windowed canvas.

In White Wedge with Genitive Object (2009–2011), the material does not act as a coating but as the very substance of the work. Costa uses highly pigmented acrylic paint to construct a solid object, freeing color from the canvas surface and transforming it into three-dimensional volume and mass. The paint thus appears as a compact, dense, and tactile sculpture. The work is organized around two axes: form and title. The “white wedge” presents an elemental geometry that emphasizes the materiality of the solid acrylic above any figurative reference. Far from neutralizing, the white draws attention to texture, mass, and the light that moves across the surface.

The term “genitive object” refers to grammar, introducing a conceptual layer that shifts the reading toward the logic of language, linking formal abstraction with an implicit semantic structure. In this way, the form is defined not only by its material presence but also by the conceptual relationship suggested by the title.

Elena Dahn

S/t, 2014/2025

Col. Oxenford

Elena Dahn works at the intersection of sculpture, performance, and materiality, exploring how soft or elastic materials—textures, surfaces, and physical tensions—activate the organic, the bodily, and the architectural. Her work investigates the tension between object and action, inviting viewers to inhabit spaces where body and matter mutually condition one another and generate new ways of understanding support, volume, and time.

In this work, first exhibited at Fundación Proa in 2014, Dahn applies plaster directly onto the wall, emphasizing a presence that is both constructive and performative: the result depends as much on the experimentation with the material as on the artist’s movements as she strikes it against the surface. By incorporating pigments, she highlights what would normally be a neutral surface and articulates her interest in the transformation of soft materials into forms that evoke tension, gravity, and memory.

Jimmie Durham

Red Flag, 2007

(Bandera roja)

Col. Cherñajovsky

Jimmie Durham is considered one of the most influential conceptual artists of the 21st century. His research has focused on what occurs “outside of language,” exploring the relationship between forms and concepts, challenging Western rationalism, and embracing uncertainty and paradox as creative horizons. To address his concern with deconstructing hegemonic and colonial narratives, he has employed drawing, installation, video, and sculpture.

In Red Flag (Bandera roja), the artist does not present a flag but the idea of one. The small sign—a kind of poetic instruction—asks the viewer to imagine a strip of red fabric waving in the sun, its tones shifting between pink, orange, and purple. This displacement turns the political banner into a mental image and, at the same time, into a minimal object supported by a precarious structure.

The critical—both political and visual—gesture lies in this absence: the work evokes the flag associated with revolutionary left, communism, or warning, yet refuses it in its literal materiality. In its place, a simple device activates the viewer’s imagination, presenting a flag that exists only as a possibility, stripped of its emblematic weight and reduced to a fragile, almost failing suggestion.

Dolores Furtado

My Bite, 2014

(Mi mordisco)

Col. Oxenford

Through sculpture, Dolores Furtado interrogates the sensuality and visceral presence of the body and its fragments. She uses materials such as plaster, resin, and metal to construct a universe that exists on the threshold between the intimate, the organic, and the inorganic.

My Bite (Mi mordisco) condenses the artist’s fascination with the traces and limits of corporeality. Plaster, with its ability to capture the smallest details, preserves what would normally be ephemeral; its whiteness and final hardness evoke the matter of bone or dried flesh. The title refers to a fleeting physical gesture, charged with desire: the bite as both contact and temporary mark on the flesh.

By working with plaster, Furtado transforms this instantaneous action into a solid, enduring form. The sculpture functions as a material memory, compelling the viewer to confront the intensity and fragility of the encounter. My Bite does not depict a body but materializes a sensory tension: the trace of an experience that persists in a silent, ambiguously living form.

Fernanda Gomes

S/t, 2011

Col. Cherñajovsky

Fernanda Gomes’s Untitled (2011) embodies a poetics of the essential and the light. Using minimal materials—wood, nails, and paint—the artist transforms everyday elements into a sculptural reflection on presence, space, and light. Her nearly monochromatic palette, dominated by white, does not aim to erase form; rather, it turns the piece into a sensitive surface capable of intensifying variations in ambient light and the shadows that pass through it.

In dialogue with Arte Povera and Brazilian post-minimalist practices, Gomes works with modest, precarious materials to question traditional notions of value and monumentality in sculpture. By assembling wood and nails, she leaves the gesture of the hand exposed, while the final structure reveals a delicacy that invites careful observation. The work asserts itself not through scale or technique, but through the way it makes the relationships between object, space, and perception resonate.

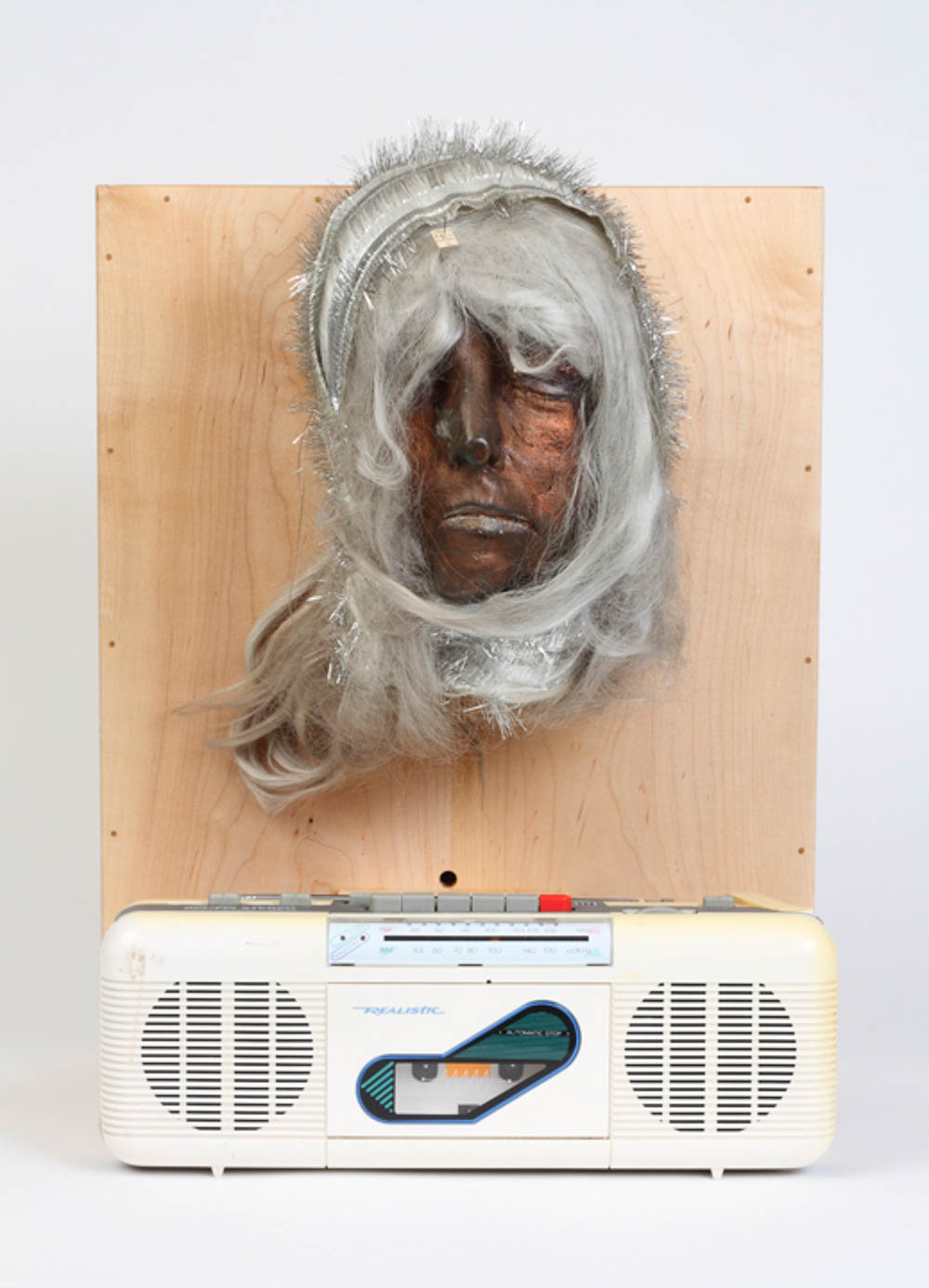

Lynn Hershman Leeson

Self Portrait as Albino, 1968

Col. Cherñajovsky

Her work investigates the relationship between humans and technology, forms of identity, surveillance, and the use of media as tools of empowerment in the face of censorship and political repression.

Self Portrait as Albino marks the artist’s early interest in fictional identities and the subversion of representational regimes. The photograph documents a performative act in which she transforms her own appearance to embody the figure of the “albino,” exploring the limits of otherness and the social constructions that define what is considered normative.

By manipulating her image to occupy a space of visual marginality, she uses the body as a conceptual device. The intensity of white emphasizes both hypervisibility and the condition of the “other,” questioning who defines normality and how physical appearance shapes identity perception.

The work’s sonic dimension is conceptual: it is activated in the encounter with the viewer. The image functions as an inverted listening device, amplifying the observer’s mental noise—the immediate judgment, categorization, discomfort, or fascination—forcing confrontation with the social narrative projected onto marginalized identities. In this sense, the photograph operates as a visual microphone that exposes the internal mechanisms through which we construct and reproduce the figure of the “other.”

Estefanía Landesmann

Fig. 5, 2021

Col.Oxenford

Her practice focuses on image, materiality, and space, observing the peripheral and barely visible aspects of urban, institutional, and architectural environments. She uses photography as both medium and material to explore material realities and their structures of value.

Fig. 5 functions as a visual diagram that questions the presumed truth associated with photography. The inkjet print transforms the image into an object: a fragment of paper that preserves a moment yet resists being mere documentation.

The work is part of a broader investigation into reality in seemingly insignificant places. The title introduces a pseudo-scientific quality that contrasts with the piece’s poetic and abstract character, allowing for an open-ended reading. Here, photography intersects with sculpture and installation, where textures, light, and unusual scales give density to the everyday.

Martín Legón

La fenomenología, 2013/2025

Col. Oxenford

Martín Legón explores the construction and circulation of images, archives, and systems of knowledge through assemblages, collages, installations, and elements drawn from historical research and literary criticism. This work, first presented at monumental scale at the Centro Cultural San Martín in Buenos Aires, reimagines the logic of the bureaucratic archive to create an installation that evokes a funerary memorial.

Each box contains—according to the inscription on the floor “headstone”—a minimal fragment of existence: a trivial object, a single word, or even emptiness. With humor, irony, and a touch of strangeness, the work invites viewers to look differently at the things that surround us and shape our own lives.

Mariana López

Sobres , 2010

Biromes, 2013

Almohada, 2021

Jean, 2021

Reloj, 2021

Remeras, 2021

Col.Oxenford

For over a decade, Mariana López has been developing a project that directly interrogates the exercise of representation in art, particularly in painting. While the ambition of painting to encompass everything—capturing the world and translating it into a plastic reality—is not new, it is less common to see this aspiration shifted toward the realm of objects.

Using the materials of painting—pigments and canvas—López constructs colored replicas of everyday objects, proposing a unique form of mimesis in which the work does not refer to an absent model but visually and spatially replaces it. In this shift, “re-presentation” becomes “presentation”: painting ceases to function as an image and becomes an object, while the exhibition space transforms into a field of simulation where the boundaries between the real and its copy become unstable.

Tomás Maglione

The Knife Constitución, 2016

Col.Oxenford

Maglione’s practice is built from actions carried out in the street and in open spaces, where contact with the urban environment activates processes of recording, collecting, and assembling. Debris, fragments, and discarded materials enter his work not as arbitrary waste, but as traces produced by the public space itself. Even pieces created in the studio retain this exposed condition, as if left open to the elements.

Maglione transfers these processes to the exhibition space, challenging the normative modes of circulation and perception in the city. Through videos, photographs, drawings, texts, assemblages, and mixed media, he constructs a fragmented urban experience, where the everyday functions as a field of experimentation rather than a stable setting.

In his videos, the image does not precede the action: it emerges from the interaction between body, camera, and environment. These are unscripted situations governed by simple rules that allow for contingency. The camera, often attached to the artist’s body, modulates the distance from which the city is observed.

In The Knife Constitución, filmed in Buenos Aires, he records a space between two highways near Constitución Station. Instead of focusing on vehicle or pedestrian flow, the camera lingers on a sunbeam cut by shadow. Through silent and still observation, the work suspends a territory defined by circulation, introducing a different temporality in a space historically tied to railway infrastructure and the contestation of public space.

Fabián Marcaccio

Dólares - Rapto Paintants, 2007

Col. Oxenford

Since the 1990s, Fabián Marcaccio has developed a practice that pushes the traditional boundaries of painting. Initially known for his sculptural manipulations of the canvas’s two-dimensional surface, he later incorporated digital and industrial processes that expand the pictorial field into hybrid forms he calls “paintants.” In these works, manipulated image, sculptural form, and painted surface intersect in three dimensions.

Based in New York for nearly four decades, Marcaccio explores what painting can do when it distances itself from the representable, questioning its own limits through a persistent intersection of conceptual reflection and material experimentation. His production ranges from large-scale murals to pictorial sculptures that detach from the stretcher and operate in an unstable threshold between disciplines.

The work presented here was part of the exhibition Rapto, where the artist addresses, through various pieces, the extortionate kidnapping of brothers Juan and Jorge Born by Montoneros in 1974–1975. In this “paintant,” Marcaccio reproduces the 61 million dollars of the ransom paid in 1975: a monetary block in the process of becoming something else. It is neither entirely painting nor sculpture, but an object whose materiality embodies a tension between value, form, and instability, and whose fate—like that of the money itself—remains open.

Rivane Neuenschwander At a Certain Distance (Public Barriers), 2010

Col. Cherñajovsky

Rivane Neuenschwander’s work lies at the intersection of the ephemeral and the participatory, exploring chance, order, and our relationship to objects, languages, nature, and social rituals. Her installations often involve audience participation, as the artist dismantles the everyday to reveal the invisible logics that sustain it: geography, identity, popular culture, and a philosophical dimension of time.

At a Certain Distance (Public Barriers), first presented in 2010, stems from her research on the public fences used to demarcate construction sites and private property in Brazil. These barriers, made from simple and often improvised materials, rarely fulfill the protective function for which they were designed. The installation brings together found and constructed objects in wood, glass, metal, concrete, stones, and plants, emphasizing chance as a guiding principle. Its arrangement changes with each presentation: it may enclose an empty space or encircle itself, suggesting a path without imposing one while simultaneously incorporating everything happening around it.

Juane Odriozola

Acciones, 2025

Col. del artista

Juane Odriozola works with minimal, everyday materials to explore how repetition, rhythm, and accumulation can transform the simple into a complex visual system, in dialogue with abstraction and minimalism. His practice is grounded in an economy of means: he intervenes with papers, scraps, or surplus materials and converts them into modules that, through repetition, generate formal relationships tied to color and geometry.

In the installation created specifically for this exhibition—an aligned row of roughly thirty flags made from hand-painted paper towels—Odriozola pushes this method to its limit. Each flag is an operation requiring meticulous manual work, yet taken together they form a device that oscillates between the fragile and the constructive. His work reveals how the minimal, when repeated and reorganized, can produce an image that challenges our assumptions about the value of materials.

Damián Ortega

Estructuras de la casualidad IV, 2009

Col. Cherñajovsky

Damián Ortega is known for transforming everyday objects—cars, tools, household utensils—into sculptures and installations that dismantle the familiar to reveal their structural components, hidden meanings, and symbolic tensions. His work invites reflection on materiality, consumption, industrial history, and the social relationships underlying each object.

In Estructuras de la casualidad IV (2009), Ortega presents a suspended sculpture that freezes the very moment of instability. By disassembling a solid mass into multiple numbered plaster spheres, the work becomes a molecular diagram that questions our perception of form and operates in the tension between order and chaos. This decomposition is not a destructive act, but a revelatory one: it exposes the invisible forces—gravity, tension, interdependence—that govern our structures, whether physical, social, or conceptual.

Ultimately, this work is a meditation on relativity, where empty space is as defining as matter, and dispersion becomes the new cohesion.

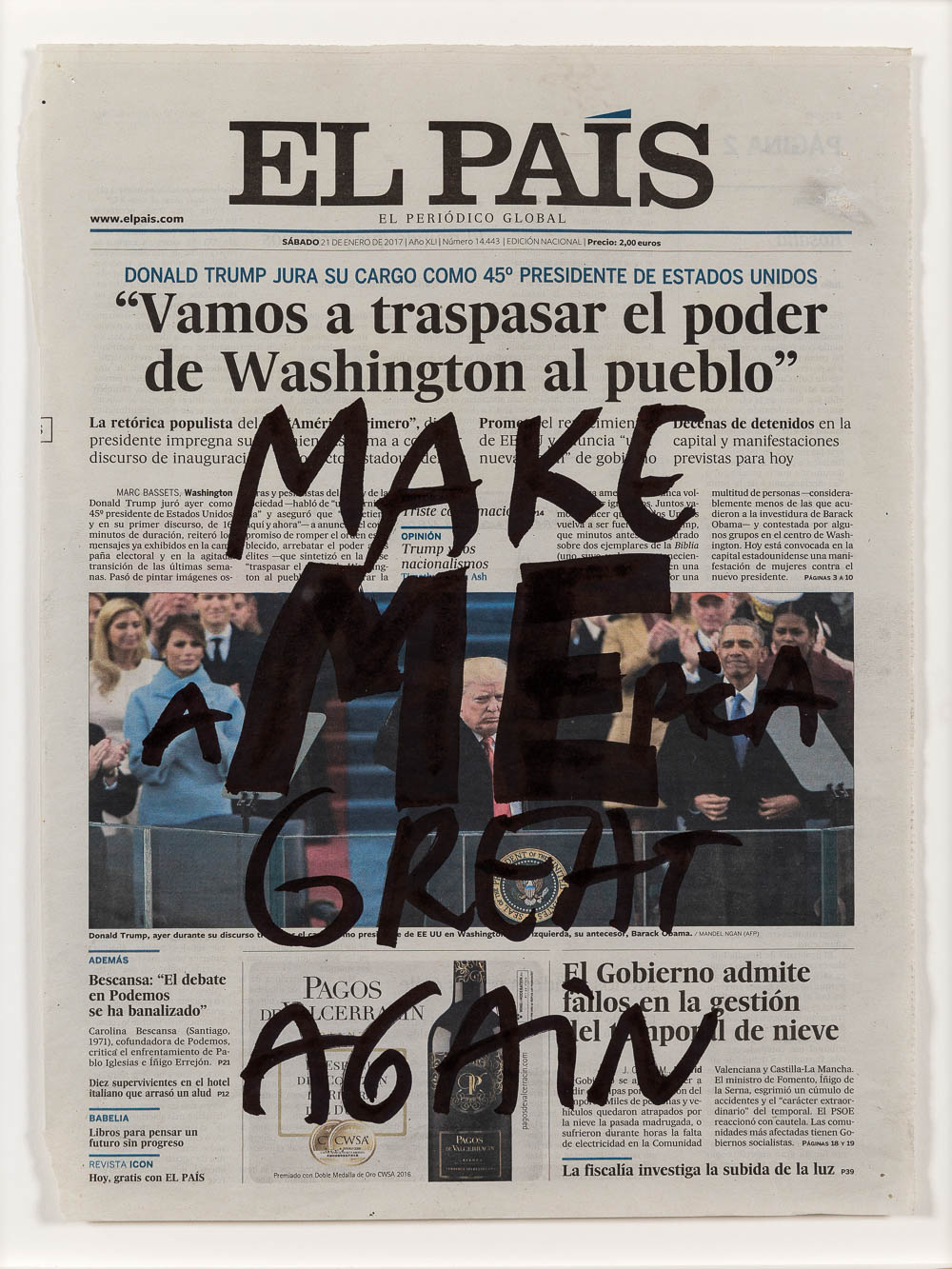

Dan Perjovschi

El País 21.01 Make Me (America) Great Again, 2017

Col. Balanz

Dan Perjovschi’s work El País 21.01 Make Me (America) Great Again (2017) encapsulates his distinctive approach: art as urgent, direct, everyday commentary. By intervening on a newspaper page with black ink, Perjovschi transforms an ephemeral medium—the day’s news—into a platform for political and social critique with more lasting impact. He takes the slogan charged with U.S. political discourse and places it within the context of international press, expanding its resonance and revealing its global implications.

His work relies on a strict economy of means: quick lines, schematic figures, and gestures reminiscent of caricature. This formal simplicity allows the message to be immediate and accessible, almost like a marginal note that nonetheless conveys a sharp reading of the international situation.

Here, the work does not reside solely in the drawing, but in the clash between the artist’s ink and the newspaper’s typography. This intersection of journalism and art highlights the unavoidable intertwining of politics, information, and popular culture, showing how Perjovschi turns the everyday into a tool of critical resistance.

Amalia Pica

Eavesdropping, 2011

(Escucha clandestina)

Colección de J. K. Brown y Eric Diefenbach

Amalia Pica’s work examines systems of communication and the ways individuals participate in the collective, probing the codes—linguistic, gestural, architectural, or bureaucratic—that organize social life. She uses simple materials and everyday objects to explore how information circulates, how it is misinterpreted, concealed, or celebrated. Her works engage with recent political history while proposing collaborative actions, performances, and sculptures that activate new forms of encounter. Her practice reveals that communication is always fragile, incomplete, and yet essential for imagining shared bonds.

In Eavesdropping (2010), Pica transforms a domestic gesture—listening through a glass to what happens behind a wall—into a public device that reorganizes the relationship between viewer, artwork, and space. By multiplying the glasses and placing them at different points along the wall, the artist constructs a constellation that suggests invisible acoustic lines. At the same time, she sets up a perceptual tension: the audience knows they can “try to listen”, but often hears only their own whispers or the ambient noise. Eavesdropping exposes the boundary between the public and the private: the glasses operate as an interface for sound and, simultaneously, as a metaphor for the desire to communicate.

Marcelo Pombo

Michael y yo, 1989

Col. Oxenford

In the 1980s, he worked as a special education teacher and was an active participant in the Grupo de Acción Gay. His first exhibition, in 1987, reflected influences from psychedelia, rock, and gay culture. From the early days of the Centro Cultural Rojas, he was part of its artistic scene, developing work characterized by materials and techniques drawn from decoration, crafts, and domestic handiwork. This universe of “minor” resources became, for Pombo, a way to construct affection, identity, and style.

In this context, Michael y yo (1989) encapsulates the period’s sensibility and the artist’s intimate relationship with mass culture. Through collage—combined with everyday objects like ashtrays and matches—Pombo transforms the figure of Michael Jackson into an object of personal devotion, a small domestic altar where the popular becomes a tool for self-identification and desire. The portrait ceases to be a distant homage and becomes an emotional projection: an image in which aspirations, affinities, and fantasies are recognized.

As Inés Katzenstein notes when analyzing the Rojas scene, Pombo “built an aesthetic of the affective and the handmade that challenged the hierarchies between high culture and popular culture.” Michael y yo fully embodies this approach: an intimate gesture that elevates humble materials to assert a unique form of sensibility, desire, and belonging.

Valeska Soares

Any Moment Now.... (Spring), 2014

Col. Balanz

This installation, first presented in New York in 2014, brings together 365 book covers mounted on canvas, one for each day of the year. Organized into four sections that evoke the seasons—autumn, winter, spring, and summer—the work offers a journey through titles of different genres, languages, and geographies, ranging from literary classics to popular fiction.

True to her practice, Soares dematerializes the book by separating its covers and titles from their original support and presenting them in a new context. In doing so, she activates associations that depend on each viewer’s point of departure and personal path; the texts and images evoke individual memories, emotions, and cultural references according to their setting. In this way, the installation turns reading—real or imagined—into an experience in constant movement.

Adrián Villar Rojas The Theater of Disappearance (1), (4), (6), 2017

Col. Balanz

Adrián Villar Rojas works across multiple media to create immersive environments that seem to move continuously between different times and spaces. His practice has evolved toward the design of mutating systems—both organic and inorganic—that form unpredictable microcosms in which future, past, and alternative versions of the present coexist as a transforming whole. This world-building responds to a central question in his work: What would happen if we could observe ourselves, as humanity, from an external, detached, almost foreign perspective?

Each project begins with an immersive process in the social, cultural, geographic, and institutional context where he works alongside a team of collaborators. This method defines him as an itinerant artist who, through travel and sustained research, has forged deep connections with different places around the world.

The Theater of Disappearance, presented in 2017 on the rooftop of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is one of the most striking examples of this approach. The project involved extensive collaboration with several museum departments—heritage, archaeology, conservation, decorative arts—to select more than a hundred pieces from the collection. Through digital scanning, 3D printing, and casting techniques, the artist created replicas that he reorganized into a living environment charged with symbolic tension.

The installation takes the form of a sculptural banquet: tables arranged on a checkered floor, human figures asleep or frozen in ambiguous gestures, hybrid objects, vegetation, and furnishings that evoke a suspended ritual. The scene dismantles the linearity of art history and proposes a fragmented narrative in which the ancient and the contemporary coexist on the same plane. In this sense, the notion of “disappearance” does not imply destruction but transformation: the objects detach themselves from their original function and reappear in an altered universe where time and memory are rewritten.