Interview with Cai Guo-Qiang

by Adriana Rosenberg and Rodrigo Alonso

I want to believe. Guggenheim Bilbao, 2009.

Selected text by Alexandra Munroe and Sandhini Poddar.

"I use animals because people were used for propaganda."

Interview by Elena Cue.

Ninety-nine tales. Curious Stories from My Journey through the Real and Unseen Worlds.

Cai Guo-Qiang.

Cai Guo-Qiang

Cai Guo-Qiang

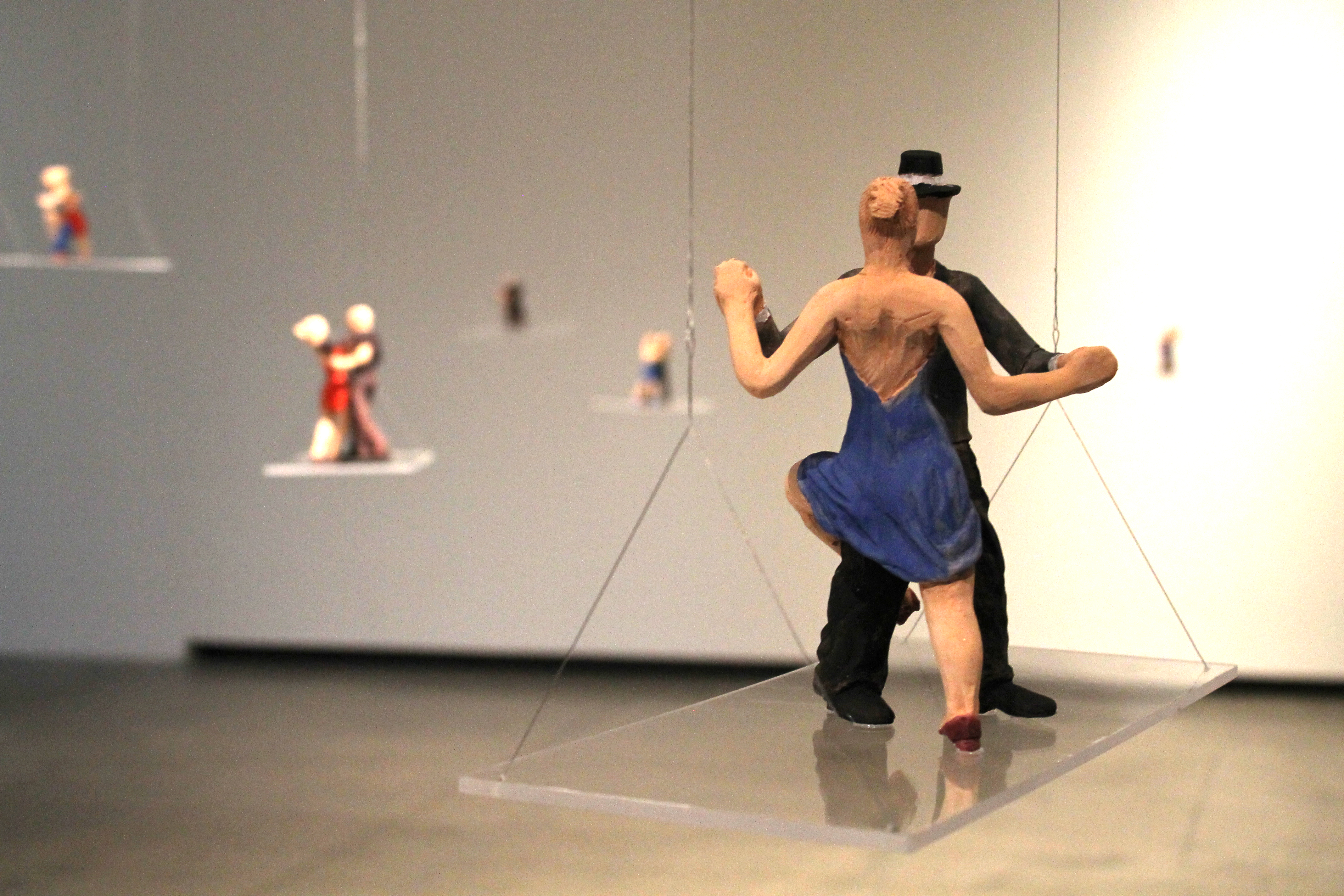

Cai Guo-Qiang, La vida es una milonga

Cai Guo-Qiang, La vida es una milonga

Interview with Cai Guo-Qiang by Adriana Rosenberg and Rodrigo Alonso

Adriana Rosenberg/Rodrigo Alonso: How did you prepare the exploratory trip to Argentina? What was the relationship between your expectations and the encounter with the place, its spaces and its people?

Cai Guo-Qiang: When I was in Mexico, my impression of their culture, their land and people was one of sunshine and solitude. This led me to use mezcal later on to express the yang,or positive energy, and the bold generosity of the people, who are also quite isolated and melancholic. In Brazil, I tried to put the emphasis in my work on the frenzy during Carnival; it is untamed yet utopian and feels slightly surreal. Particularly with the flying machines, submarines and robots inPeasant Da Vinicis, the works feel as though they have come from a utopian world.

So when it came to Argentina, I thought to myself, what will I find here? Later on I realized the more I try to learn, the less I know about the relationship between Argentineans and the land they live on, and their sense of identity. Whether it is art and culture, politics or economy, there are many difficult conundrums. In that way Argentina is full of puzzles and riddles, and from my mental dialogue with the country, my impression is that she is an enigma. Yet what attracts me to her is that she cannot be easily understood; she makes you feel lost and perplexed and that things are not that simple. This is different from what I first imagined. I realize that there are many unknowns, and it is not that easy to draw conclusions. I am both mystified and intrigued by the enigma, and as I continue this exploratory journey, the feelings of incomprehensible and unresolved are becoming more and more evident. Argentina is more complicated than I imagined, and she is not so straightforward.

AR/RA: We have noticed that in the project for our country you have selected some popular icons such as tango and craft pottery, what place does the popular occupies in your artworks and in your thoughts?

CGQ: First of all, everyone is all too familiar with tango, so it is difficult to turn it into art. For an outsider to discuss tango is an even riskier and more difficult proposition. That said, tango is so popular in Argentina, and it never ceased throughout the years—from its inception to the present day—and it is tightly intertwined with the destiny of the country and has managed to influence the entire world. There must be a reason why tango has become a symbol of Argentina and a means of understanding Argentinean culture. Tango embodies the culture and spirit of the people living on this land, their character and aesthetic, the rhythm of Argentina and her temperament are all illustrated in the dance. That is why I chose this challenging direction to be the portal or bridge and to manifest my dialogue with Argentinean culture. It also enables me to once again to initiate a discourse with local culture—a major aspect of my artistic practice and concepts. Whether I am in Doha, Ukraine or Paris, I absorb the spirit and aesthetic of that land by experiencing their local culture, and I reinterpret it with my art.

My dialogue with local culture may include engaging with folk traditions such as pottery, in which the material (such as their soil or clay) is used to initiate the exchange. At the same time I continue to use the same materials I have always used—gunpowder, paper and fireworks—to explore new possibilities. This time for instance, in one of the installations, I am exploding gunpowder on terracotta, rather than on paper, which brings new challenges. In the outdoor project Life is a Milonga: Tango Fireworks for Argentina I use pyrotechnics to illustrate the rhythm, movements and moods in tango, as well as the bandoneón. New requirements naturally emerge, so I have to change and adapt my artistic medium and style to make pioneering developments.

AR/RA: In your artworks there is an ongoing relationship, sometimes more subtle, others more clear, between certain aspects that reference Eastern traditions and Western contexts. Is this relationship present when developing projects or does it arise naturally?

CGQ: I use gunpowder and paper, so it is easy to give people the impression that I am working with Eastern traditions. When I make my work using inventions such as gunpowder and paper, the gunpowder fumes create ink wash-like effects on paper. However the process also encompasses the idea of “creation through destruction,” and the instantaneous transfer of energy at the moment of explosion; the artistic conception transcends the East and the West. When I use these materials—gunpowder and paper—to render scenes from the Argentinean and Latin American landscape, or use gunpowder and canvas to depict tango and themes in tango songs with Western-influenced painting techniques, the synthesis of these styles and methods will take place naturally. This is not intentional, because I tend to “go with the natural flow” when I make art, and to “leverage others’ strengths to exert my own." When I work with different cultures and use different materials, I borrow and exert their strengths to build this foundation. Although this philosophy may sound quite Eastern, the results are not about whether the artwork is Eastern or not.

Although the works on paper have not yet been made, I hope to absorb nutrients from the nature and people of Argentina, and create works that are more abstract, more relaxed, simpler and with a sense of hazy emptiness. When the composition is absent of details, I leave something unbeknown to myself, and allow viewers to experience something mysterious. With the works on canvas, I also hope to try out the things I learned from the painting traditions of Southern Europe. Some of the drawings may have similar compositions to religious paintings, creating a relationship with God or the mystical in nature.

AR/RA: Gallery Room 1: Life is a milonga. Some of the concepts we noticed in this artwork are: the childlike, the dreamlike, the playful or ludic character, the scenic, and the narrative character. Could you expand on these issues?

CGQ: After visiting several milongas, I observed several different types of behaviours at a milonga: There are people sitting on the sides waiting to join the dance; people walking over to join the dance; and a mélange with people, lights and music of all sorts—dancers paired in diverse combinations as groups watch from the sidelines. Comprised of people from all walks of life, the scene forms a microcosmos of human society, with several layers swaying and moving in tandem. Through this installation work, I really hope to express my uncertain yet boundless impressions of the milonga, and the lives of the people in it.

The swaying swings form a relationship with the music boxes, and the swings themselves have a mystique to them, in that they are associated with people’s childhoods and fantasies. In the gallery, the music boxes play La Cumparsita, and the seemingly magical dancers, as you pointed out, look playful and whimsical. It conveys a significant event and an important theme in a relaxed and fun way.

AR/RA: Sala 2: Gallery Room 2: We are interested in your thoughts about painting becoming installation / scenery, the recovering of landscape and your dialogue with our country geography, as well as the place of the viewer. Some words about the productive process of this piece and the incorporation of the local art community in the actual production.

CGQ: When placed in the gallery, the colossal sheets of paper become spatial works, because they can bring viewers into the scene of the drawing. Unlike traditional paintings that frame the landscape like a window, the drawings form a space of their own. Yet in order for me to figure out the content of each drawing and the relationship between the drawings, I need to bring my body into nature, taking a walk in the geographical and cultural environments of your country. Once I get a sense of the landscape, I can return to make the drawings, using my body once again to feel the landscape: the mountain ranges, or the clumps of dried grass on the mountains. I need to experience the landscape, because when I make the drawings, the paper is laid on the floor. I use my arms and hands to rub and push gunpowder, my body hovers over the drawing as I work, then I decide where to ignite the fuse and where to add weight on top of the drawing to intensify the explosion. This process allows me to re-experience the energy of the landscape, so I may converse with nature again. The explosion enables me to feel the relationships in energy: the cascading waterfalls, the movement in valleys and so on. When audiences observe me creating the work, they will see that I am taking a journey in nature as I am drawing. Like me, they are also embarking on an adventure, and waiting for gunpowder to bring about a magical, instantaneous transformation both before and after the ignition. Everyone is following me on this journey, a process during which they will experience the same excitement and anxiety as I do, in anticipation of this unknown destiny.

There are two main aspects that define my collaboration with local communities. First is the participation of volunteers, who work together with me. Although I may have decided where to draw the mountains and bodies of water, the volunteers will have a much better understanding of the landscapes they grew up with. When they help me draw or cut stencils for these features, they will bring their understanding with them, so my work can be more grounded in this land. Even if the volunteers are not very familiar with the natural environment outside of the city, they are the proprietors of this land. They breathe the air here and eat fruits grown locally, so their sensibilities will be different from mine. For these drawings, I will also be using gunpowder and materials made locally.

Second, I also invite members of the public from local communities to oberve as I create the artwork; this becomes a public event. When audiences discuss or chat amongst themselves, their movement and their voices (to me it is all a foreign language) all affect my mental state and perspective when I am making the drawings. All these elements will help me reach a state, where I can create works in Argentina specifically for Argentina. What remains unchanged is my understanding and subjectivity, therefore my explanation and interpretation of this place comes from me and me alone. I cannot say, “This is what Argentina is,” because it is only one person’s interpretation. In art, it is important to have multiple interpretations and diverse visions.

Cai Guo Qiang, trabajando en Buenos Aires, 2014

AR/RA: Gallery Room 3: Series of portraits. We do not have too much information. Can you explain the series of portraits?

CGQ: This is a relatively bigger mystery and unknown that I have left for myself this time. When I work on an exhibition, I usually leave one gallery with an uncertain outcome, so I can give myself a little surprise and create some anxiety. This time, at first I wanted to draw on cowhide leather; for a variety of reasons, I am now using canvas instead. I intentionally made the canvases tall and narrow, so the proportions are similar to altarpieces, alluding to Medieval and Renaissance painting. Unlike the works on paper that have horizontal compositions, the works on canvas are vertical. I am hoping that in these vertical compositions, multiple timelines will move simultaneously: viewers will be able to see the movements in tango—as well as the spirit and temperament in tango music—while the songs and the choreography convey the zeitgeist of an era in Argentinean history, say for example, the Golden Age or the Great Depression. The disparate elements will alternate on these vertical drawings, challenging the way I use gunpowder on canvas. It will also challenge the energy of the gunpowder, as these layers will coexist, leading me to explore how to represent this overlay of information. I will have to exercise my brain, and think carefully about how to connect these stories and how the energy will travel across the canvas.

AR/RA: Room 4: The value of the document in your work, what does the video gives you as a tool? Do you consider that documents are part of your artwork? Why did you decide to divide the explosions between night and day?

CGQ: My works are fleeting and disappear in an instant. Spectators on site use their bodies and minds to register the energy and the things that touch them about the work. Although video documentation cannot completely and perfectly re-create the experience of watching the work unfold on site, it helps people who have seen it explain to others who have not seen what happened; they can use the video as a means to help them elaborate upon what touched them the most. It is not perfect, but at least those who have seen it can say “wow.” Then, those who have not seen the work but saw the video are given the chance to imagine, and thus, they can more easily understand what happened.

The video documentation itself is not video art, but when I place several videos together in a space, this can become my installation work. This time, I am trying to divide the explosion events into: daytime, nighttime and the ones in between. Daytime explosions take place under the sun and are made with smoke; night time explosions rely on light; those at dusk between day and night –primarily the Projects for Extraterrestrials series, which create chaos within time and space – are made with primitive gunpowder and fuse. In the gallery space, the videos depict day, night and the transition between the two, forming a new time-space relationship. This marks the first time I am using this concept.

AR/RA: Ceramic artwork for the Bookshop: Why did you choose the ceramic and the floral image? Is it the recovery of the local landscape or you consider they could be universal motifs?

CGQ: On my first site visit to PROA, I sensed that a flowering vine could hang in the space above the bookshop. I envisioned the vine to be sculpted from clay, and since flowers and plants grow from soil, they could be made out of an earthy material like clay. After gunpowder is exploded on the flowering vine, it will resemble a three dimensional gunpowder drawing, forming a relationship with the other gunpowder works.

The way I see it, all my works employ universal motifs. However, this vine should be more immediate and intimate, because flowers and plants are more relatable than say, big landscapes, the tango or swings.

AR/RA: Most of the artworks in the exhibition relate to the burned: fabrics, paper, ceramics, do you consider it a mark or signature of your work?

CGQ: I have indeed exploded gunpowder on paper, fabric and ceramics, and people may think that is my signature. But what I am more concerned about is whether I can use gunpowder to capture my sensations of being mystified by Argentina, and of trying to seize the unknowable. Can I use gunpowder to bring out the ethos of this land and its culture, even if it cannot easily be verbalized? This will create value for my use of gunpowder in Argentina; otherwise wouldn’t it be the same if I use gunpowder in Mexico or Argentina? But if I manage to capture the feelings I experience here and depict them in the works, the work I make in Argentina will be different. No matter which country I travel to, I must look for a reason to justify the use of gunpowder.

AR/RA: The making of fireworks creates a dialogue between the public space (outside) and the exhibition (inside). Can we talk about of a unique event?

CGQ: Making gunpowder drawings for the indoor exhibition is like an artist’s private and intimate activity. Even if the dimensions of the works are large and the content rich, it is after all an artist’s personal mental exploration, and the works are the result of the artist’s visceral activity and process. Therefore, I often compare an artist who is making drawings indoors to an artist who is making love, whereas outdoor explosion events are more like revolutions that take place in society, between heaven and earth, or between the sea and the shore. The culture and history of La Boca, from past to present, are all caught in the same vortex, alongside the history and culture of Argentina. The explosion event allows my work and ideas to depart from my mental realm as an artist, and become a participatory experience, a movement. During those two hours on that evening, the hundreds of thousands of people on the shores of Vuelta de Rocha will mingle, creating with the tango fireworks on water. It will be a unique chapter both in the history of tango and in my own artistic career, as we each continue to develop further in different places across the world.

Source:

From catalogue Cai Guo-Qiang: Impromptu. Proa, Buenos Aires, 2014.

I want to believe. Guggenheim Bilbao, 2009.

Selected text by Alexandra Munroe and Sandhini Poddar.

Gunpowder Drawings by Alexandra Munroe, Samsung Senior Curator, Asian Art, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Cai Guo-Qiang’s drawings made from igniting gunpowder explosives laid on paper constitute a new medium of contemporary artistic expression. Together with the explosion events to which they are conceptually linked, Cai’s gunpowder drawings convey his central idea of mediating natural energy forces to create works that connect both the artist and the viewer with a primordial state of chaos, contained in the moment of explosion. They also demonstrate his central interest in the relationship of matter and energy; in these works, matter (gunpowder) explodes into energy and reverts to matter in another state (the charred drawing). In this way, they are charts of time, process, and transformation.

Cai’s gunpowder drawing process has been likened to the practice of a shaman who invokes agents of a spirit world to cause a reaction in the material realm. For the drawings, Cai frequently uses sheets of Japanese hemp paper whose manufacture he specially commissions; its fibrous structure withstands and absorbs the impact of the explosion and the incineration of the paper to beautiful effect. Placing these sheets on the floor, he arranges gunpowder fuses of varying potency, loose explosive powders, and cardboard stencils to create silhouetted forms over the paper’s surface. Here and there, he lays wooden boards to effectively disperse the patterns resulting from smoke and the impact of the explosion. He then weights all these elements in place with rocks to intensify the explosion. Once the setup is completed, he ignites a fuse at one end of the work with a stick of burning incense. Then, with loud bangs, the ignited gunpowder rips across the surface of the paper, lighting the array of explosives according to its designated pattern and engaging artist and onlookers in a momentary encounter with the spectacular power of explosive destruction. A second or two later, the paper lies burning in clouds of acrid smoke. Assistants run to stamp out any embers with rags. Finally, the drawing is removed from the floor and hung up vertically for the artist’s inspection.

Cai Guo-Qiang,Dibujando con polvora, 2014.

Cai’s production of gunpowder drawings can be organized into two periods: from his first drawings in 1989 to 1995, when he was living in Japan; and from 1996 through the present, while living in New York. During the Japan period, Cai produced two major series of gunpowder drawings that were directly connected to the development of his explosion events. These are Projects for Extraterrestrials and Projects for Humankind. The majority of the gunpowder drawings—whether a multi-panel folding-screen or a single sheet of paper—were created as diagrams of Cai’s conceptual ideas and proposed visual designs for specific explosions, what scholar Wu Hung refers to as Cai’s “think pieces.” That some projects were ultimately realized while several never were is insignificant in recognizing these drawings as stand-alone works of art. In formal terms, the gunpowder drawings of this period evolved from images of pure abstraction to more representational compositions that suggest physical structures. Since his move to New York in 1995, Cai’s mastery over his materials has resulted in gunpowder drawings that are increasingly complex as both technical and pictorial feats. Working with a wider range of fuse grades and explosive chemicals, some of which he has designed in collaboration with professional pyro-technicians, and using more elaborate stencils and weights to outline forms and to control the explosions, Cai has further established gunpowder drawings as his primary artistic medium.

Explosion Events by Alexandra Munroe, Samsung Senior Curator, Asian Art, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

China’s most famous invention, gunpowder, literally meaning “fire medicine” in Chinese—which is a mixture of saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur—was originally discovered by Daoist alchemists in search of an imperial “elixir of immortality.” Best known for his explosion events, Cai began using gunpowder and fuse lines to create explosions for public audiences using the ground and existing structures as a framework. These early works lasted between one and fifteen seconds. Since then, Cai’s practice has evolved dramatically. He now produces aerial explosion events that are often developed with professional pyrotechnicians. Most recently the artist has harnessed computerized technology to create more elaborate explosion imagery, whose effects last as long as twenty minutes. The explosion events are usually realized through commissions by museums, art biennials, or national and international agencies. Cai’s explosion events are primarily created with gunpowder while others are designed as celebratory spectacles in the tradition of fireworks displays (Cai derides this term). But they are also contemporary works of art with charged conceptual, allegorical, and metaphorical narrative.

Cai Guo Qiang, Vortex 2006, polvora sobre papel, 400 x 900 cm.

Cai’s explosion events are related in sheer scale to site-specific Land Art projects, where art disrupts the land by employing it to radical aesthetic use. But whereas most Land Art is static and semi-permanent, Cai’s explosion events are spectacularly transient. As time-based works created for live public audiences, Cai’s explosion events operate as performances, whose impact—thunderous bangs, fiery light, smoke, and floating debris—conjures both violent chaos and ritual celebration. And in the tradition of ephemeral art, the explosion events become known only through their documentation—photographs, videos, and drawings.

Cai’s explosion events are often titled by series: Projects for Extraterrestrials; Projects for Humankind; and Projects for the 20th Century. The titles tell us something about the scale and perspective of Cai’s thinking. The giant patterns of fire on earth signify a code, or the aspiration to communicate a code, to “extraterrestrials,” by which Cai means realities or forces that are alien to our mundane existence. By harnessing fire as an ancient and constant element of geological formation, social ritual and religious purification, and life’s destruction, Cai’s explosion events produce, however momentary, an experience of temporal dislocation, a momentary trance when we feel ourselves to be at the beginning and the end of life on earth. The explosion events represent Cai’s central interest in both ancient and modern cosmological science.

Social Project by Sandhini Poddar, Adjunt Curator, Asian Art, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Cai Guo-Qiang is a peripatetic, transnational artist whose work explores and challenges the function and meaning of art within a wider social sphere. Central to his practice is the contraction of site-specificity with a conscious transcendence of cultural and temporal limitations. Responding to the conditions of each new location for a project, Cai approaches its place, patrimony, and indigenous practice with the sensibility of an archaeologist or historian. Cai commenced what may be termed as his Social Projects in the early 1990s, working with non-art sites and volunteers outside of the professional art world to create spaces for debate. These ongoing experiments and interventions carry out the artist’s utopian ideals of social engagement and mobilization, with a sustained belief in the transformational nature and the potential for dialogue within communities of people. Examples of Cai’s Everything is Museum series, wherein the artist assumes a curatorial role and appropriates non-art spaces for temporary exhibitions involving local communities, will be exhibited in the museum’s Sackler Center for Arts Education.

Source:

From the catalog Cai Guo-Qiang: Impromptu. Proa, Buenos Aires, 2014

"I use animals because people were used for propaganda."

Interview by Elena Cue.

Complete review: http://www.abc.es/cultura/arte/20140916/abci-entrevista-qiang-201409131825.html

Cai Guo-Qiang can be described as one of the world’s most recognized Chinese artists. He was born in 1957 in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, China, a city known for its cultural openness and religious diversity, due in no small part to its coastal location. He moved to New York in 1995, where he began producing, social- and cultural-themed works, but it wasn’t until the end of that decade, coinciding with the sudden breakthrough of Chinese art in the rest of the world due to broader Chinese reform and change within the country, that his work began to be exhibited in the US.

How has the spiritual influence of that kind of upbringing–growing up in an era where the Chinese Communist Party was undergoing a process of ideological affirmation– affected the artist you are today?

The political movements during the Cultural Revolution employed tactics that motivated large crowds. Having witnessed and even taken part in some of the parades during that period, I later applied the same strategies to my art practice. For instance, I often work with large groups of volunteers from local communities to realize my artworks. My goals may be different from the political leaders’, and the ways in which I work with large groups of people may also be different, but it is evident that I am influenced by these experiences from my youth. People of my generation were taught [by Chairman Mao], “to rebel is justified”, and we were told to disregard figures of authority. As a contemporary artist, this gave me the courage to step away from tradition, explore new mediums and new ways of working, and to transform traditional iconographies with my own visual language.

He studied stage design at the Shanghai Theatre Academy, and he tried his hand at cinema by participating in two martial arts films. He also dabbled in violin and theatre, and has a wonderful voice that I personally have had the pleasure of hearing. His father, a traditional painter and calligrapher, would paint landscapes on matchboxes, and was a great influence on the artist. “A small space can easily be filled with the corners of the earth”.How have all these experiences shaped the person you are today?

At the Shanghai Theater Academy, the training I received in stage design was different from the art academies at the time. I learned many different approaches to come up with creative ideas: from working freely with different materials, to studying spatial compositions, and these help me create diverse forms of art. The collaborative team spirit and the performance aspect, the emphasis on dramatic effects, the focus on audience interaction or participation in theater, and the temporal nature in artistic expression—all helped shape characteristics of my work.

In 2008 the Guggenheim Museum organized your retrospective Cai Guo-Qiang: Quiero Creer (I Want to Believe), this exhibition was presented in New York, Beijing and Bilbao, and featured works spanning over two decades of your art production. What does Cai Guo-Qiang want to believe in?

I Want to Believe was is a comprehensive examination of my early works, many of which express a deep-seated curiosity towards the universe and the unseen worlds around us. The exhibition titletherefore encompasses encompassed all these possibilities, whether they are extraterrestrials, principles of feng shui and Chinese medicine, or metaphysical forces and worlds not visible to the human eye. It expresses expressed an attitude and a sense of anticipation.

Vista de la Instalación "De Frente" en el Museo Guggenheim Billbao, 2009

What meaning do you ascribe to the Plautus’ phrase “Man is man’s wolf”, popularized by philosopher Thomas Hobbes?

Growing up, I saw how figurative paintings depicting human subjects—either political leaders or soldiers at war—were used as tools for propaganda, and have thus avoided portraying people in my work. To tell stories, I often use animals as a metaphor for human behaviour. Animals are more natural, more spontaneously expressive than humans, and they can be more easily integrated into exhibition spaces and themes.

With your 1995 installation for the Venice Biennale, what did you bring to Venice that Marco Polo had forgotten?

The year 1995 marked the 700th anniversary of Marco Polo's return to Venice from China after a maritime journey that began in Quanzhou, my hometown, so I decided to make a joke on Marco Polo. He brought back many stories of the East to the West, but he did not tell the West about Eastern thought and philosophy, so I sought to remedy this oversight by bringing Chinese herbal medicine from the East to the West. I brought an old-fashioned fishing junk brought from Quanzhou, and navigated it along Venice's Grand Canal from Piazza San Marco to Palazzo Giustinian Lolin.

The boat docked outside the palazzo, and functioned as a seating area where visitors could savor the medicinal tonics and potions offered inside. Within the palazzo, a modern vending machine was installed on one wall to dispense five varieties of bottled herbal tonics for 10,000 lira each. These drinks were formulated according to the ancient Chinese principle of “five elements,” wherein the five elements of natural phenomena (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) correspond to five tastes (bitter, sweet, sour, spicy, salty) and five organs of the human body (liver, heart, spleen, lung, kidney). The prescriptions posted on one wall enabled participants to select remedies suitable to their needs.

(...)

Your interest in time and space, opposite forces and cosmology are evident in your work. What is your guiding philosophy in life?

In the I Ching, or the Book of Changes, “I” means “change”, and this is important. There are also two doctrines I embrace in Daoist philosophy: “no law is the law”, and “leveraging others’ power to exert your own strength”. In Confucianism, tolerance is a value that has taught me not to exclude others, and to learn from and work with people of different cultures; it enables me to find new possibilities in art. These underlying principles are the most valuable lessons I have learned from Eastern philosophy, and they are more important to me than superficial symbols (such as dragons), or even gunpowder as a choice of artistic medium.

Source:

Diario ABC, Spain, 2014. (Fragment)

Cai Gui-Qiang, Front 2009, installation at the Guggenheim Billbao Museum.

Cai Gui-Qiang, Front 2009, installation at the Guggenheim Billbao Museum.

Hometown of Cai Guo-Qiang. Quanzhou, China.

Hometown of Cai Guo-Qiang. Quanzhou, China.

Cai Guo-Qiang.

Cai Guo-Qiang.

Cai Guo-Qiang, new languages ​​for new times.

Cai Guo-Qiang, new languages ​​for new times.

Ninety-nine tales. Curious Stories from My Journey through the Real and Unseen Worlds.

Cai Guo-Qiang.

The following selected fragments, originally published for the exhibition Ladder to the Sky (MoCA, Los Angeles, 2012), are include in the exhibition catalog Caig Guo-Qiang: Impromptu,published by Proa Foundation in occasion of the first exhibition of the artist in the country. In these little vignettes written in first person, Cai rebuilds his life and work: from his early childhood memories associated with their origin and place in a remote village in China, where he learned to recognize the existence of the "visible and invisible worlds" until its international projection as a recognized avant-garde artist.

1. The Fengshui in My Hometown, Quanzhou

Quanzhou was first built during the Tang Dynasty and has a long and rich history that dates as far back as 718 CE. During the Southern Song Dynasty (around 1238 CE), the inhabitants grew concerned that the fortunes of the city had begun to decline, and they invited a sage for advice. The sage noted that Quanzhou city had been planned in the shape of a carp, lying along the river with its head pointing toward the ocean—an auspicious position indeed! But the sage further observed there was a major problem posed by the nearby city of Yongchun, which stood upriver atop the mountain behind Quanzhou. As Yongchun continued to grow, twisting and turning downriver, it had expanded into the shape of a fishnet, which was having the unfortunate effect of trapping the carp downstream that is the spirit of Quanzhou. As a result, the sage advised the citizens of Quanzhou to erect a pair of pagodas in the city, which could pierce through the fishnet of Yongchun.

Quanzhou’s citizens began by constructing a long sloping mound to haul stones up to the top, burying many houses along the way. To this day, the two stone pagodas are still the highest in China. Afterward, Quanzhou prospered and flourished, becoming the world’s largest port from the Song through the Yuan Dynasties.

I was born in a city that staunchly believed in fengshui.

5. Father’s Story: Home on a Matchbox

After my nana’s stammer was cured, she kept her promise to the shaman and left the small fishing village for the city, taking with her my dad and my mom. When my mom was only thirty-six days old, her mother was due to leave for Malaysia. She worried that the baby wouldn’t survive the voyage at sea, so she left my mom in the care of my nana, who was her good friend. After my mom had grown up, Nana couldn’t bear to let my mom leave the family and marry someone else, so she arranged for her to marry my dad, her son. My parents didn’t love each other, and the marriage became a tragedy forged by feudal marriage practices. However, the tragedy became the pride of our hometown: my forty-year-old nana taking her grandson, me, across the Luoyang Bridge.

My father loved traditional Chinese ink-wash painting, reading, and practicing calligraphy. He once worked as the manager of an antiquarian bookshop, which in the early 1950s, just after the founding of the People’s Republic, was a decent job. Lots of people came to sell their antique books, and my father used his earnings to buy lots of classical calligraphy copybooks, as well as to build up a large book collection. When I was little, trails of Quanzhou literati used to come to our house and recite books, paint, and do calligraphy. My nana was self-employed and made a living by selling seafood, so our cultured guests would bring some wine to go with Nana’s stir-fried seafood. Back then, everyone had very little, but my father was the kind of man who would spend anything he could spare on his passion for the arts. Thus, our house became a literary salon, and I grew up in an intellectual environment.

When the storm of the Cultural Revolution neared our door, my father grew nervous. He silently burned his book collection at home in the dead of night for many nights in a row. Father is timid; he is an honest man with a big heart, but he has always acted very cautiously. While I obeyed him most of the time, I also wanted to rebel. Of course, there is nothing wrong with being honest and moral, but it is hopeless to be an artist who doesn’t dare to do anything. For instance, Father used to spend day after day practicing calligraphy in the style of Yan Zhenqing (709–785 CE), believing that only once he mastered Yan’s style could he develop his own. He always scolded my penmanship as a mess, and only later admitted that I sort of had some style of my own: “Tsk, tsk,” he would say. Strictly speaking, my father was my first artistic influence. He made me feel that art requires at least a little revolution, and it had to start by attacking my weaknesses.

When I was small, I was always made to sit on his lap and roll his cigarettes. My deepest memory of him involves him puffing out clouds of cigarette smoke and drawing landscapes on matchboxes with his pen. The matchbox landscapes had mountains, rivers, the sea, seagulls, boats, waterfalls, and clouds. Sometimes one matchbox would be one individual drawing; sometimes many matchboxes composed a small scroll. I used to ask him what place he was painting, and he always replied, “Home.”

Many years later, I went to where my family once lived, to sweep my grandfather’s grave, only to discover that the reality was completely different from the scenes my father had painted all those years. My family came from a small fishing village outside Quanzhou. While it’s not exactly flat, there’s only one small clump of hills. My grandfather was buried under a large banyan tree where the shoreline arcs inland and forms a small bay. There were only a few houses, a few boats, and a few seagulls. The place Father painted on the matchboxes had towering mountains that ranged for miles and miles, surrounded by wisps of clouds and mists; down on the sea, thousands of sails bobbed, everything composed together, a beautiful, picturesque scenery.

As I grew older and became an artist myself, I began to understand my father gradually. His was a particularly Chinese, poetic expression of the pursuit of aesthetic beauty, encompassing a boundless horizon in a mere square inch. His emotional world is in fact far wider and deeper than a small matchbox.

11. Immortal’s Footprints

When mother and I went to the mountain to worship Buddha, we often passed by a shady forest, where the rays of the sun filtered by lush trees created sparse spots. People called this place Water Flow Pit because water from the spring ran over many, many rocks there. Later, when Hong Hong (then my girlfriend, now my wife) and I went to the mountain to paint en plein air, we always took a break at Water Flow Pit to have snacks and talk romantically before walking back down the hill. One time, Hong Hong sprained her ankle, and I carried her on my back from the top of the hill, one step at a time, over Water Flow Pit, all the way down the hill. Of course, this is another story.

What made Water Flow Pit unforgettable was not its breezy elegant surroundings, which made me unaware of time passing. Rather, it was the magically indented footprints on the rock, which the locals named “Immortal’s Footprints.” By 1989, after spending a few years abroad, I began developing Bigfoot’s Footprints: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 6, a proposal that entails gigantic footprints walking across national borders. It was not until 2008, at the Beijing Olympic Games’ opening ceremony, that the giant footprints finally walked over the central axis of China’s capital city. I think the Immortal’s Footprints I saw at Water Flow Pit might have been the earliest spiritual notion I had with “footprints.”

15. My Father, the Recluse

The end of the Cultural Revolution saw the downfall of the Gang of Four, and the reforms began. My father started to grow dissatisfied with the realities of Chinese society. He was a member of the Communist Party, and when he saw so many foreign investors coming, ushering in so many aspects of capitalism, he realized that the Chinese Communist Party no longer stood by their principle and relied on the people to build their own country. China was selling itself out and deteriorating.

Yet he was a coward despite his dislike of what was happening. He was scared to leave the party. He simply stopped working and took to the mountains, where he hid in a temple like a monk. In fact, he didn’t believe in Buddhism one bit; he believed in Marxism, Leninism, and Maoism, and he thought feudal superstitions were wicked. Fearing that we would get him in trouble, every time we lit incense at home we did it behind his back, to avoid him speaking ill of the practice. Every year on the anniversary of my grandfather's death, for example, my grandmother would make my grandfather's favorite food, and we’d all eat it together. But my father would say, “He is already dead; what’s the point of cooking all this food? You should have cooked more for him when he was alive. When I’m dead I want nothing…” Such strong yet “correct” words. My grandmother was always afraid that his disrespectfulness would offend the gods and render the rituals ineffective.

Eventually we had to go visit my father, this unbeliever who had chosen to live in a temple. We didn’t know how he was doing up there in the mountains, and we were worried that he was inconveniencing the nun who lived there. My father was on sick leave, so he still had a salary. At that time, the local villagers were decent and considerate, and everyone within the work unit got on very well, so no one reported him. Every month someone would come on a bike to deliver his wages. Thinking back, I still feel very grateful. After we got his wages, we’d go to buy some food and take it to the nun by way of thanks.

Only later did I discover that my father spent his time mapping all of the thousands of stone steles on the mountain: what was written on them, who had written the inscriptions, which dynasty they were from, and so on. Many of them had been covered by moss, abandoned and taken over by nature. He also practiced his calligraphy on the tiled floor of the temple using a broom dipped in water, no need for paper or ink. During the day he looked over the faraway hustle and bustle, and by moonlight a town of lights kept him company. The traces of water calligraphy faded with the wind. No one knows how many skeins of sorrow he wrote away.

We’d ask him back down from time to time because my grandmother missed him. I made a really good oil portrait for the nun and developed a good relationship with her. She was in her late eighties, and she hung my painting in the temple. She used to order my father, “Go down and don’t come back for a week, or I won’t let you stay here.” Sometimes we stayed the night up there; the walls and ceiling were smoked black from all the incense burning, and we would watch the lights come on one by one in the town.

My father dedicated his life to art, never participated in any art activity, and yet he told me that there were museums like the Guggenheim out there. In 2008, as if a dream came true, I had a retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York. I exhibited his ink wash painting of a hundred tigers alongside my nine-tiger installation Inopportune: Stage Two to show people how I inherited and transformed my heritage. I took the catalogue back to show my father. He was always boasting about being fit for his age; indeed, up to his sixties he was always so youthful and healthy, with radiant skin, and he didn’t seem old enough to be my father. He fell ill in 2006, and when I went back in 2008, he could no longer speak. When he saw that I took his work to the Guggenheim, it seemed to me he nodded slightly, and tears welled up in his eyes.

17. Wan Hu and the Escape from Gravity

An old Chinese manuscript that ended up in America chronicled that during the early Ming dynasty, sometime in the fourteenth and/or fifteenth centuries, there lived a man named Wan Hu who attempted a bold experiment. He made two large kites and attached them to either side of a chair. Then he strapped forty-seven rockets underneath the chair, sat down, and had his assistants light the fireworks. In the midst of loud bangs and spurts from the rockets, Wan vanished in a cloud of smoke and flame. Humankind’s first attempt to fly a manned rocket was not a success. In a book from 1945, American science writer Herbert Zim describes Wan as the first person to attempt to use rockets as a vehicle. Wan is also mentioned in a Soviet textbook on rocket science as the first visionary to attempt to carry a man into space using solid fuel rockets. Thus, when US astronauts landed on the moon, they named a crater after Wan Hu, the Wan-Hoo crater.

For many years now, whenever Wan comes to mind, I find myself strangely moved and longing for the day when I might fulfill his aspiration and launch a chair into space using rockets.

Note: This story references Pan Jixing’s book, The Four Great Inventions of Ancient China: Origins, Spreading, and Their Impact on the World, Beijing: University of Science and Technology of China Press, 2001).

18. Space

When I first arrived in Japan, I couldn’t find anyone to host an exhibition of my work, since I was only a young man from China, and they believed China had no contemporary art. Eventually a friend introduced me to Gallery Kigoma on the outskirts of Tokyo, and they hosted my exhibition. The gallery space was tiny, around 2.5 by 4 square meters. I bought paper curtains that greatly resembled hanging scrolls in traditional Chinese and Japanese households. I exploded many holes in the curtains with gunpowder and hung them from the ceiling at various angles. Since the room was so small, I used mirrors to expand the space, making it an installation, a relatively young genre that was just starting to gain more recognition in Japan. At the time, both the media and I always had to explain specifically what an “installation” was. The installations, titled Space No. 1 andSpace No. 2, placed emphasis on the fragility of the scorched paper, giving the work a gentle beauty.

TV channels and newspapers began to cover my work. Gradually, the Japanese art world sought me out for exhibitions. Later, articles circulated discussing why Japan’s own traditional materials didn’t give rise to art that contained a similarly bold vision. Soon I went on to develop the Project for Extraterrestrials series. At the time, it all looked very scientific, and it was talked about in scientific-sounding terms: space, the universe, black holes, the Big Bang theory. But people also very clearly understood the Eastern elements and philosophy I incorporated in my work: chaos, creation through destruction, and so on. The Japanese audience shared the same cultural outlook and immediately related to these concepts.

Cai Guo-Qiang. Polvora sobre papel.

Cai Guo-Qiang. Polvora sobre papel.

Source:

From the catalogue Cai Guo-Qiang: Impromptu. Proa, Buenos Aires, 2014.

19. Earth SETI Base: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 0

Prior to realizing the first of my Projects for Extraterrestrials in 1989, I had come up with a project that did not involve exploding gunpowder. I later came to refer to it as Project for Extraterrestrials No. 0.

I was living in Japan at the time, and often heard the Japanese discuss the short supply and high demand of land, and territorial controversies. Thinking about the possessive desire for land among humans led me to this project: To create a public base on Earth, in search of extraterrestrial intelligence. First, locate a small island on the sea, visible from a coastal town—for example, some small island off of the shore of Kobe.

Then, level a large, rectangular patch of land with a cultivator, and lease it from the owner—be it individuals, corporation, or the state—for a hundred to even a thousand years. People would keep a constant eye on this patch of land, waiting for any sign of extraterrestrials. Perhaps one morning they would see something, and they would have to decide whether it was the work of aliens or human beings.

very aspect of the project would be part of the artwork, from obtaining land rights to the eternal wait. Humankind has already left so many marks on this planet, and the more we make the harder it gets. Plus there is less and less land available, so perhaps the best thing to do would be to set aside a patch of “useless” land, and wait for a “grand master” to come from afar and create something.

The change of the Earth’s seasons will paint its colors on this parcel of land. Does the universe have a change of the seasons, too?

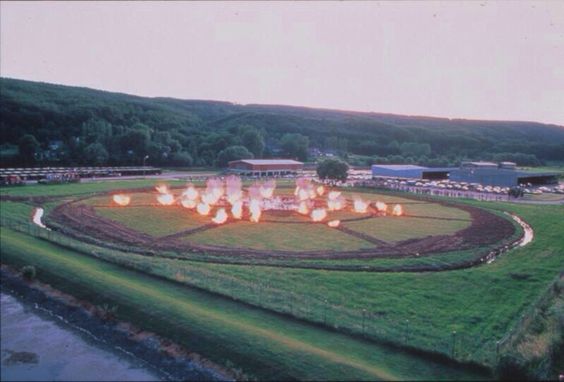

25. 45.5 Meteorite Craters Made by Humans on Their 45.5 Hundred Million Year Old Planet: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 3

After my Ascending Dragon project was aborted, I designed an ephemeral memento to address the earth’s history — meteorite craters. This would serve as a reminder of our planet’s finite existence, and a hint at the origin and the demise of mankind. For one month, my team, local volunteers, and I dug forty-five and a half “craters” by hand in an open field. Each crater signified one hundred million years of the earth’s existence. Each pit was then covered with a straw-and-papier-mâché mixture. Once the mixture was sun-dried, gunpowder was placed at the bottom of each pit, with a layer of soil on top, and all the craters were connected by an eight-hundred-meter fuse. Detonation occurred at dusk; the instantaneous spread of flames and smoke blended with the warm afterglow of the setting sun, reflecting each other.

All planets and stars are born from explosions and die from implosions; this is the destiny of every living thing. This project aimed to awaken humanity to be more aware of their surroundings, and to regard their destiny from a perspective beyond our planet.

27. Fetus Movement: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 5

This project occurred on top of a mountain overlooking the Seto Inland Sea of Japan. Using a bulldozer, a rectangle area was flattened into a “canvas,” some several thousand square meters in size. Then, as if sowing, gutters were dug and lined with fuse, connected with packets of gunpowder, and then covered and smoothed out with dirt. When ignited, the ground shook and flames spurting from underground like rows of crops sprouting. A seismograph recorded the explosion as well as the earth’s movements just before and after, registering the planet’s movements unknown to us, and the resonance between human behavior and Earth. What we felt was similar to the fetal movements of Earth.

During that period of several years, I was intrigued with two ideas: visual perception from the universe, and the interaction and dialogue between man and the universe. Gunpowder was my main medium when exploring these ideas. I hoped the moments of explosions would meld into the continuous movement of the universe, the movement that has been going on ever since the Big Bang.

30. Fetus Movement II: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 9

This explosion took place at the Bundeswehr-Wasserübungsplatz military base in Hannover Münden, Germany. The violent nature of the site prompted me to incorporate a healing element, applying the concept of “flowing water does not spoil” from fengshui. We dug a small ditch to bring in water from the nearby river, in an attempt to restore the military base to its natural balance. Inside the area surrounded by the ditch, fuses were placed in three concentric circles and eight lines connected the circles on the radius, representing Earth’s lines of latitude and longitude. The fuses were then attached to packets of gunpowder and covered over with dirt. Nine seismographs were installed around the site. I sat on a circular island at the center of the concentric circles, surrounded by a second ditch. With assistance from German and Japanese scientists, I was fitted with both an electrocardiograph and an electroencephalograph.

I lit an incense stick and placed it on the fuse. As the incense stick slowly burned away, I silently intoned the passage from Laozi’s Dao De Jing, There was something formed amid chaos, and it came into being before Heaven and Earth.” After a few minutes, the incense stick set alight the fuse. Instantly the ground and the sky were shaken, and everything was blurred by the flames and the smoke.

After the smoke had cleared, everyone saw that I still sat calmly in the middle of the island. The various devices recorded the activity of myself and Mother Earth at the very instant of the explosion and in the moments just before and after. To the great surprise of the scientists, my recorded heartbeat and brainwaves remained very calm both leading up to and shortly after the explosion. Still more surprising to them was a curious seismic wave that was recorded not long after the explosion. It seemed like an echo coming from Mother Earth. This project linked together life and the universe into an integral whole. It presented the fetal movement at the birth of the universe, quantifying the too-messy-to-unravel relationship between humankind, Earth, and the universe.

31. Project to Extend the Great Wall of China by 10,000 Meters: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 10

The project was realized when I lived in Japan. At the time, I hoped to explore the primordial need to build walls and the relationship between humanity and the universe. On my site visits to the Great Wall, I walked along the wall and observed a number of different materials used in its construction: rocks, bricks, earth. Some sections were built in winter by pouring water continuously over a mixture of earth and straw, creating a barrier of frozen earth. The placement of the Great Wall was determined according to the principles of fengshui, which becomes clear when the wall is viewed today from satellites. The line of the wall perfectly demarcates a precipitation gradient: land on the south side of the wall is suitable for agriculture, while the arid land to the north can only be used as pasture.

My ancient Chinese ancestors never stopped building walls. In this, they were no different than humanity today. The realization of my project, however, depended on collaboration between the local people and a group of tourists from different countries. The explosion project started from Jiayuguan, at the westernmost end of the wall. The budget I had was minimal, so I organized a tour group of Japanese volunteers, and I used a portion of the proceeds from the tour to cover project expenses. The tourist-volunteers worked with the locals to lay down a ten-thousand-meter fuse extending from the terminus of the wall into the Gobi Desert.

Fetal Movement II: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 9. Made at the military base Bendeswehr-Wasserübengsplatz, Hann, Münden, 1992

Fetal Movement II: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 9. Made at the military base Bendeswehr-Wasserübengsplatz, Hann, Münden, 1992