About the exhibition

The exhibition "What the Night Tells the Day" was conceived by the Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (PAC) of Milan and co-curated by Andrés Duprat, current director of the National Museum of Fine Arts, and Diego Sileo of the PAC. It was inaugurated in November 2023 in the halls of this prestigious institution, and today Proa presents it in Buenos Aires.

This exhibition takes its title from the homonymous novel by Argentine writer Héctor Bianciotti, published in 1992. The storyline, which narrates life with his Italian immigrant parents and his own migratory experience to Europe, intertwines with the careful curation of the exhibition.

The exhibition presents a series of works by twenty-two Argentine artists spanning from the mid-20th century to the present. Although heterogeneous, the ensemble can be read as a catalog of representations of different modes of social criticism and various forms of violence captured by the sensitive antennas of the artists.

Organized into four axes, the exhibition includes historical pieces but focuses on pieces by contemporary artists who work with diverse techniques, formats, and themes. The ensemble of works traverses topics ranging from social criticism, urban and rural violence, to the relationship between nature and humanity, historical revisionism, the duality of perception/reality, among others.

The first room features works by Lucio Fontana, the renowned Italo-Argentine artist, León Ferrari, winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, as well as Argentine artists who migrated, such as Alberto Greco and Liliana Porter, as an introduction to the concept of migration and the links between Argentina and Italy.

The second room brings together installations by Nicolás Robbio, Leandro Erlich, Eduardo Basualdo and Jorge Macchi, textual drawings by Ana Gallardo, and a video performance by Mariana Bellotto.

The following axis puts into dialogue and tension works by Matías Duville, photographs by Miguel Rothschild and Alessandra Sanguinetti, two pieces of political historical imprint by Cristina Piffer and Adriana Bustos, and an installation by Graciela Sacco.

The fourth axis presents works by Mariela Scafati, two photographic series of actions by Marta Minujín and Liliana Maresca, photographs by Adrián Villar Rojas, a documentary film by Tomás Saraceno, and a sound object by Juan Sorrentino.

The journey through the different personal poetics that "What the Night Tells the Day" traverses showcases the genius of the chosen artists to observe and analyze society from critical, intimate, and original approaches.

Finally, in the documentary room, a video is presented with the testimony of the curators and various images of the exhibition in Italy and Argentina.

Interview to Andrés Duprat

This interview was conducted by the Press Department of Fundación Proa.

How does this project come about, particularly the choice of theme?

When we started working with Diego Sileo, co-curator of "Argentina. What the night tells the day," the idea was to present a panorama of modern and contemporary Argentine art. Through several conversations, we determined that a overarching idea, one that would encapsulate the exhibition or that panorama, was the convulsive social and political aspects of Argentine history, from the nation's founding actions in the 19th century through the Desert Campaign to the sequences of military dictatorships and the political, social, and economic fluctuations of the 20th century.

It's not an exhibition of political art, but rather through the work of 22 relevant artists - in addition to their individual poetics - the ensemble reflects a society that, while going through these convulsions, on the other hand (which would be the positive side), also shows great creativity, the great creative reaction that Argentines have to negative contingencies. The ensemble enhances and multiplies the idea of a society that has been shaped through episodes of violence and injustice, but at the same time has demonstrated sensitivity and reaction, a society as uncomfortable as it is mobilized, rebellious and daring, which has never, not even in its most tragic moments, lost its critical capacity, irony, inventiveness, and even corrosive humor. That's somewhat the spirit that somehow frames this great collective exhibition of Argentine art.

What were the complexities of the chosen theme when following the curatorial script?

Actually, curating any exhibition has its complexities. In this case, it lay in generating a heterogeneous ensemble that also had cohesion based on the chosen theme. The title of the exhibition, "What the night tells the day," also speaks to that, of the two sides of a reality: that nocturnal, ominous, secretive thing with certain negative connotations, and the day representing the opposite. We liked that metaphor described by Héctor Bianciotti, the great Argentine writer, because it expresses that dichotomy between the negative and the positive, the lights and the shadows. It didn't bother us at all to delve into complex themes of local history such as the military dictatorship and its tragedy, social violence, etc. I believe that artists are exponents of a poetic way of expression, often more effective than any text, so it seemed to us a good lens to show fragments of Argentine history through their eyes.

What was the selective criterion when gathering the artists?

The idea was to present a panorama of contemporary Argentine art. In that sense, we decided to include modern artists so that, in a way, they provide a framework and establish connections with the contemporary ones. In line with that idea, we chose works by paradigmatic figures such as Lucio Fontana, who is even a disputed artist between Italy and Argentina because he carried out his activity in both countries; León Ferrari's Western Christian civilization, which is a masterpiece of Argentine art history and refers to the Vietnam War, and a performance by Alberto Greco in 1963 in Rome, Italy, precisely. That ensemble frames the contemporary productions we present, which can be read around or starting from those important pieces by Ferrari, Greco, and Fontana.

How do the younger artists engage with the concept?

Regarding the selection of contemporary artists, we worked a lot by looking at a lot of dossiers and finally put together a strong group of established artists. All of them have a consistent body of work, with a recognizable image, and it seemed to us that, while their poetics are different, each one has the necessary strength to show an absolutely powerful panorama of Argentine art. We didn't choose very novel or very young artists, but rather focused on the middle generation with significant work behind them.

About the process of reconciling points of view and personal preferences when curating together, what aspect of the experience do you rescue as enriching professionally and personally?

Curating "with four hands" with Diego was a beautiful and enriching experience because of everything it implies to work with another person who has a different perspective. I develop my curatorial activity in Argentina, and I know the local art scene in detail; he is a very lucid person, perhaps with a more international and distant perspective, since his activity takes place in Italy. That combination was virtuous: in my case, I contributed the knowledge of the scene and the works, and Diego provided the freshness that distance gives, not knowing local details and anecdotes. Working together forces you to substantiate your decisions, unlike when you work alone, because one already knows what they like and what they don't, although often not quite why. When it's a team effort, you have to make a very interesting intellectual effort, not to convince the other, but to justify tastes and reasons. That exercise is very enriching, it strengthens even when you have to yield to the other's perspective, which brings a new perspective.

What are the differences between this exhibition and the one presented in Milan?

Conceptually, it's the same exhibition and exactly the same artists; what varies are some works, for example, in the case of site-specific ones done in Italy. Those were related to the exhibition space and the specific architecture of the PAC. In Buenos Aires, we presented variations and in some cases other works, always within the same spirit of the exhibition. The ensemble works very well in Proa's galleries and the tour it proposes with its spatiality. We are very happy.

León Ferrari. La civilización occidental y cristiana, 1965. Colección Familia Ferrari

León Ferrari. La civilización occidental y cristiana, 1965. Colección Familia Ferrari

León Ferrari, 1920–2013, Buenos Aires In 1965, León Ferrari presented the work Western Civilization and Christianity at the Di Tella Prize in Buenos Aires: a crucified Christ mounted on the replica of the wooden frame of a US warplane, denouncing the violence of the West, stemming from the Vietnam War, and sparking a broad debate about religion understood as the origin of violence. The artist declared: "I believe our civilization is reaching the highest degree of barbarism ever recorded." The work was submitted to the prize along with three other boxes, but a few days before the inauguration, the director of the Di Tella Institute, Jorge Romero Brest, requested its withdrawal, alleging that it offended religious sensibilities. Faced with such an act of censorship, Ferrari made the political decision to exhibit only the boxes: "I found myself at a crossroads: to follow the path of the visual arts that it suggested, or rather demanded, withdrawing everything and denouncing censorship, or to take the path of politics and continue my original idea of exhibiting precisely something about Vietnam there." "There are two types of works. On one hand, sculptures without any critical purpose and, on the other hand, works in which I use art to express opinions about what is happening: repression in general, violation of human rights, the 'Process' [Argentine military dictatorship], antisemitism, discrimination against homosexuals and women, among other topics. The church issue is just another thing. I believe that in art, you cannot establish limits or make definitions (...) it is possible that someone can prove to me that this is not art; I wouldn't have any problem, I wouldn't change my path, I would just change its name: I would cross out 'art' and call it politics, corrosive criticism, anything."

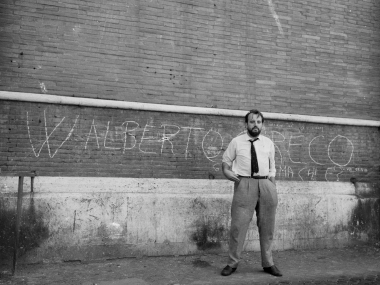

Alberto Greco. Registro fotográfico: Claudio Abate. Sin título, Albertus Grecus, 1962/2020. Colección Julián Mizrahi y Archivo Claudio Abate

Alberto Greco. Registro fotográfico: Claudio Abate. Sin título, Albertus Grecus, 1962/2020. Colección Julián Mizrahi y Archivo Claudio Abate

Alberto Greco. Registro fotográfico: Claudio Abate Sin título, (Cristo 63 performance en Roma),1963/2020

Alberto Greco. Registro fotográfico: Claudio Abate Sin título, (Cristo 63 performance en Roma),1963/2020

Alberto Greco. Registro fotográfico: Claudio Abate. Sin título, (Arte vivo, Roma) ca.1962/2020. Colección Julián Mizrahi y Archivo Claudio Abate

Alberto Greco. Registro fotográfico: Claudio Abate. Sin título, (Arte vivo, Roma) ca.1962/2020. Colección Julián Mizrahi y Archivo Claudio Abate

Alberto Greco, 1931, Buenos Aires – 1965, Barcelona

Alberto Greco began his "living art" actions in 1962 in Paris, where he exhibited a poster with the text "Première Exposition Arte Vivo," marking people and objects with a chalk circle and his signature. This marked the beginning of an intervention style that would later expand to Rome, Madrid, Buenos Aires, and New York. The documentation displayed includes scenes from the experimental work Cristo 63 at the Teatro Laboratorio in Rome, featuring Carmelo Bene and Giuseppe Lenti, which parodied the Passion of Christ. Conceived as a "spettacolo arte vivo," the performance could unfold, according to Greco, "in the middle of the street, inside a tram, or on the subway platform... with all the adventure of reality, incorporating the unforeseen." Without a script or shared guidelines, the artist invited the public to participate in creating the representation together. Scatological scenes, nudity, and excessive alcohol consumption led to police intervention. Consequently, after a brief period of detention, Greco had to flee Italy accused of blasphemy. Descriptions and memories of the theatrical experiment appear in the "Gran manifiesto-rollo del arte vivo-dedo" (Great Manifesto-Roll of Living Art-Finger), a work created later in Spain. "Living art is the adventure of the real. The artist will teach us to see not with the painting but with the finger. He will teach us to see again what happens in the street. Living art seeks the object but leaves the found object in its place, does not transform it, does not improve it, does not take it to the art gallery. Living art is contemplation and direct communication. It seeks to end the premeditation represented by gallery and exhibition. We must come into direct contact with the living elements of our reality. Movement, time, people, conversations, smells, rumors, places, and situations. Living art, Dito movement."

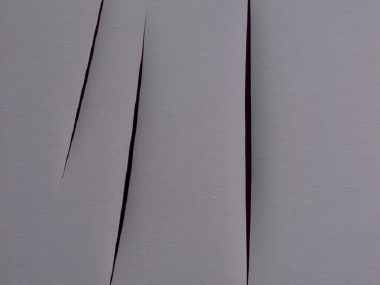

Lucio Fontana. Concetto Spaziale, Attese. Passa un jett, che voglia di partire per l´infinito, 1962. (Concepto espacial, Expectativas. Pasa un jet que quiere llegar al infinito). Colección Fundación Federico J. Klemm

Lucio Fontana. Concetto Spaziale, Attese. Passa un jett, che voglia di partire per l´infinito, 1962. (Concepto espacial, Expectativas. Pasa un jet que quiere llegar al infinito). Colección Fundación Federico J. Klemm

Lucio Fontana. Concetto Spaziale, Attese, ca. 1966-1967. (Concepto espacial, Expectativas). Colección Fundación Federico J. Klemm

Lucio Fontana. Concetto Spaziale, Attese, ca. 1966-1967. (Concepto espacial, Expectativas). Colección Fundación Federico J. Klemm

Lucio Fontana, 1899, Rosario – 1968, Comabbio "As far as I'm personally concerned, I want to emphasize that what I do is not exactly painting; it's, in any case, an expression of plastic art. The cuts and holes? Oh yes, here lies my quest beyond the conventional canvas plane, towards a new dimension: space. It's a gesture of rupture with the limits imposed by custom, conventions, tradition, but -I must be clear- it has been matured with an honest knowledge of tradition, with the academic use of scalpel, pencil, brush, color. Some time ago, a surgeon who visited my studio told me that 'those holes' he could make perfectly as well. I replied that I also know how to cut a leg, but then the patient dies. If he cuts it, however, the situation is different. Fundamentally different. It's the pursuit of pictorial space that leads him to found Spatialism, an artistic movement of the mid-20th century. Fontana used cutting tools to perforate or tear the canvas and to demonstrate three-dimensional space. With a deep reference to art history, in which space is fundamental in representation, Fontana refers to Spatialism as an artwork in line with modern times: "...man, today, flies with new techniques that surpass the wildest fantasies of previous years, and reaches other bodies in space and explores dimensions hitherto unexperienced..." The two works, acquired by the Federico Klemm Foundation in 1992 and 1995, became part of the Institution's heritage. Under the administration of the National Academy of Fine Arts, in accordance with Federico Klemm's testamentary will, these works are exhibited permanently.

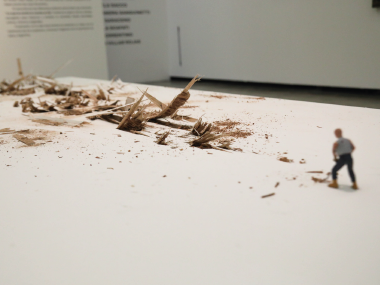

Liliana Porter. Trabajos forzados, 2024. Cortesía de la artista

Liliana Porter. Trabajos forzados, 2024. Cortesía de la artista

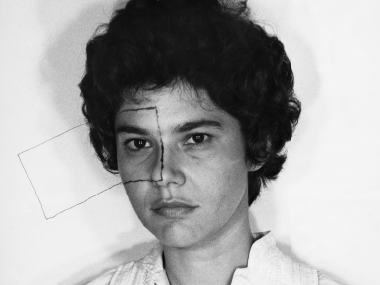

Liliana Porter. Sin título (Autorretrato con cuadrado I), 1973. Cortesía de la artista

Liliana Porter. Sin título (Autorretrato con cuadrado I), 1973. Cortesía de la artista

Liliana Porter, 1941, Buenos Aires

Workers and their actions are present in many of the artist's works. In the manner of "Works and Days," in which Hesiod dignifies labor as a good of both man and gods, Liliana Porter portrays the actions of anonymous builders of our environment. In the series Forced Labor, we find miniature sculptures where tiny characters are trapped in their chores. In this sense, the artist reflects: "My works are metaphors of reality. One is very small and what they have to resolve sometimes exceeds human scale. The man who has to sweep something endless or untangle a thread much larger than himself resembles someone trying to come to terms with reality, and it's never achieved because we never finish understanding what we're doing in this world."

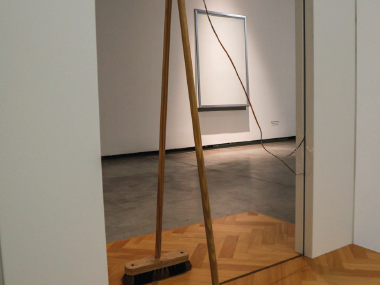

Leandro Erlich. Brooms, 2015. Cortesía del artista

Leandro Erlich. Brooms, 2015. Cortesía del artista

Leandro Erlich. Brooms, 2015. Cortesía del artista

Leandro Erlich. Brooms, 2015. Cortesía del artista

Leandro Erlich, 1973, Buenos Aires

In the universe created by the artist Leandro Erlich, surprise, misunderstanding, and doubt about the reality we perceive are constant elements. Immersing oneself in that world implies that the spectator incorporates the possibility that the work questions certain pre-established principles. The simplicity of his familiar and everyday scenes crosses the boundary between play and art. In Brooms, two identical objects are carefully arranged to create the illusion of a mirror. This apparent symmetry provokes a visual experience that destabilizes our understanding of space. By manipulating the viewers' perception, Erlich invites us to question our assumptions about reality and truth. Through the apparent simplicity of the installation, a space is opened for reflection on the nature of illusion. Thus, the piece becomes an experience in which our perceptions can be deceptive and truth relative. The work urges us to explore the limits of our own understanding and to reconsider the certainties we take for granted in our everyday lives. "What interests me is to generate that distance of non-understanding, to displace the spectator in something, but so that by themselves, without needing someone to explain it to them, they can discover things. I think that articulates an element in intelligence and is ultimately what hooks people: the satisfaction of having been able to understand things by themselves."

Eduardo Basualdo. Luciérnaga, 2017. Cortesía del artista

Eduardo Basualdo. Luciérnaga, 2017. Cortesía del artista

Eduardo Basualdo 1977, Buenos Aires Eduardo Basualdo, recognized for his focus on the intervention of space as a central element of his artistic research, creates unsettling installations that delve into the complex relationship between the environment and the viewer. In his installation Firefly, a 100-watt lamp illuminates a bedside table with red light, casting its shadow on the floor from the ceiling of the room. The interaction between the intense light and the red-tinted shadow creates an intriguing and mysterious atmosphere. Two works complement the artist's ensemble: a transparent print of a pigeon's body on glass projects its shadow on the wall. Passage evokes the marks accidentally left by birds hitting closed windows. Lastly, in Repair, Basualdo pierces the glass from side to side with a black thread at various points, creating an apparent suture around an invisible cut. This repeated device highlights the challenges present in the perception of reality, prompting the viewer to reflect on the nature of the visible and the hidden.

"Disorientation, surprise, and astonishment are very valuable states for me. They are figures that manage to break the everyday perception (...) I am interested in having the viewers' bodies tense up with the works. Introducing threat or excessiveness in the construction of the works allows for another connection with the viewers."

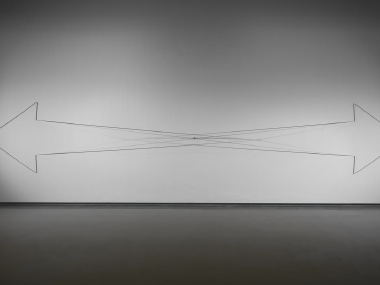

Nicolás Robbio. Estudio de tensión de la serie Confrontación de fuerzas, 2014. Cortesía del artista

Nicolás Robbio. Estudio de tensión de la serie Confrontación de fuerzas, 2014. Cortesía del artista

Nicolás Robbio. Cómo contener un territorio, 2019. Cortesía del artista

Nicolás Robbio. Cómo contener un territorio, 2019. Cortesía del artista

Nicolás Robbio, 1975, Mar del Plata Through his installation belonging to the series Tension Studies - initiated in 2010 -, the artist employs a network of cables, points, and weights to challenge the viewer's perception, questioning the dichotomy between the concrete and the abstract, the objective and the subjective. In this work, Nicolás Robbio urges us to reflect on how the introduction of a simple element or device, such as a tree branch, transforms tranquility into a tense experience, redefining space. This exercise is replicated in the terrarium How to contain a territory, from the series Aquariums, where ironically, a portion of land contained by a barricade is presented inside. "My notebooks include sequences of drawings, generally composed of simple lines, overlays of transparencies, and schematic cuts of objects that contain or are contained within other elements. As each drawing attempts to synthesize as much as possible of the structure of real objects, their layering suggests different narratives, combinations, and therefore new perspectives on the same objects."

Mariana Bellotto. Trilogía pandémica, 2021. Cortesía de los artistas

Mariana Bellotto. Trilogía pandémica, 2021. Cortesía de los artistas

Mariana Bellotto, 1963, Buenos Aires In a world moving towards dystopia, Mariana Belloto integrates other people into her research, considering bodies as a critical and political medium. Through performances, performative inventions, video-performances, and audiovisuals, she addresses topics such as consumption, the impact of human actions on nature, technology, and violence. With innovative anatomical models composed of flesh, skin, plastic, screens, hair, and masks, beings emerge that inhabit a non-degradable universe where plastic is omnipresent. She presents, in an ironic and reflective manner, a global issue stemming from consumerist society. In Pandemic Trilogy, the video begins with documentary images of a snake shedding its skin, directly alluding to the transformation of bodies in post-pandemic times. In "Technoskin," performers occupy an undefined space for a precise interval of time; a man surrounded by obsolete technology announces that he will pass through a portal, becoming a hybrid being: human figures then appear inside transparent bags, resembling human plastics, technological waste. In "Coda-Trash," a computer screen displays the accumulation of digital waste, the reproduction and disposal of images, a meeting recording, the "delete" button, and the trash can as protagonists. "We anchor our work from a perspective of the body as a critical and political vehicle. We engage with themes that, through ironic and poetic dramaturgies, invite reflection on ways of being and existing in the current world."

Ana Gallardo, 1958, Rosario

The work of Ana Gallardo initiates a profound reflection on themes such as old age, gender violence, exclusion, and death. As she herself asserts, "it becomes evident that my artistic pursuits and experiences from my private life coexist fully in my work".

Retén is a monochromatic installation that envelops the spectator: a series of large charcoal-drawn paper sheets reveal the traces of the artist's strokes, while the overlaid layers of opaque black intensify its funereal character. In each of the exhibited canvases, Gallardo has transcribed brief testimonies from Guatemalan women recounting the fears and sufferings experienced during the insurgency in the country. The handwritten texts are located at the bottom, almost at ground level, to create a certain difficulty in reading and to make it necessary for the spectator to approach metaphorically what is being denounced.

Jorge Macchi, 1963, Buenos Aires The artist says: "I limit myself to finding a familiar and well-known object that serves as a hook or excuse for the audience to enter the work in a simple way. That's why all the emphasis is placed on the formal aspects, on the qualities of the material, and that's why there is a great variety. Everything is aimed at that crucial initial moment of the viewer's approach to my work." This testimony is present in the piece "Shipping", where Macchi uses a crate - a box used for transporting works of art - on which he makes cross-shaped incisions, alluding to or creating a piece in which the cutouts refer to or synthesize the walls of a confessional. Positioned in the gallery, it becomes a wooden sculpture that allows viewing through it towards the rest of the works. This duality is what gives identity to the artist's work, who, using everyday objects, reconstructs or invents polysemic meanings of the materials and the principles for which they were made.

Matías Duville, 1974, Mar del Plata In Matías Duville's artistic quest, landscape takes on forms through drawings, installations, objects, and videos. His works explore diverse ways of approaching a territory, both real and imaginary. The piece Hogar (Home), emerged from a specific project carried out in the Argentine Pampas within the framework of the Guggenheim Fellowship, comprises a video and a series of photographs captured by the artist himself, documenting the metamorphosis of his intervention: a house unfolded in the countryside. The residence is a life-size structure built with cement and arranged on the land. "I began to reflect on the idea that there are not only four seasons, but an infinite number. The work always presents itself in a unique way," Duville comments. However, upon understanding the natural logic of the terrain, he felt the need to intervene. "I created furrows to connect the house with the lagoon and sculpted windows. As a result, guinea pig burrows began to form, and fish entered through the chimney." For some time, the cows had torn up the carpet. This architecture is designed to evoke imaginary sensations, as highlighted by García Navarro. "It possesses the essence of a habitable environment but becomes a platform with significant abstract elements. Nature sometimes manifests itself very intensely," Duville reflects. Over time, he understood that it is a work without a defined end, which will continue to transform constantly.

Alessandra Sanguinetti, 1968, Nueva York

The series On the Sixth Day unfolds in the Pampas countryside, with its animals as the protagonists, often depicted dead or near death. Alessandra Sanguinetti portrays the relationship between these animals and humans, a strong yet simultaneously violent bond, aiming to communicate a message: "Taking the life of another living being is neither a natural nor an everyday occurrence." Her fascination with the contradictory nature of "this combination of love we feel towards animals and the violence with which we treat them," is, in her own words, "to give them a new life." Sanguinetti focuses on the beauty of the environment, juxtaposed with the cruelties that occur within it: "I have always seen nature as full of life and death. [...] You open a little piece of grass and you already see dozens of bugs trying to survive. Every day, life and death are present. All the animals there have two possible destinies: either to herd those who are going to die, or to fatten up until they become food."

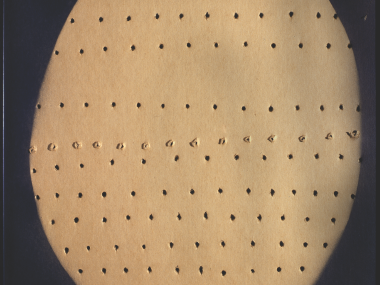

Cristina Piffer. Cien pesos, viente pesos, diez pesos, de la serie Marcas del dinero, 2010

Cristina Piffer. Cien pesos, viente pesos, diez pesos, de la serie Marcas del dinero, 2010

Cristina Piffer, 1953, Buenos Aires

With her artistic practice, Cristina Piffer addresses the economic and social history of Argentina, highlighting the violence during the consolidation of the national state. In her work, she explores the moment when Argentina became a supplier of agricultural products to the world and the need to expand into new territories, confronting the bloody military campaign initiated in 1879, which devastated native populations. Piffer points out that these endeavors not only influence our interpretation of the past but also our understanding of the present and the need to imagine more humane futures.

Adriana Bustos. Ceremonia Nacional, 2016. Cortesía de la artista

Adriana Bustos. Ceremonia Nacional, 2016. Cortesía de la artista

Adriana Bustos, 1966, Bahía Blanca In the video installation National Ceremony, Adriana Bustos relates footage of sports ceremonies that took place in the 20th century within authoritarian political contexts. The artwork, composed of two screens in the form of a diptych, connects and associates, on one hand, a segment from Leni Riefenstahl's documentary "Olympia" about the XI Olympic Games held in Berlin in 1936 during the Nazi-socialist regime of Adolf Hitler, who presided over the Games' opening. On the other screen, Bustos selects a segment from the opening ceremony of the 1978 FIFA World Cup in Argentina, during the military dictatorship (1976-1983), in the presence of General Jorge Rafael Videla. The visual selection draws an analogy between the propagandistic models of both governments, which employ the same formal and communicative modalities. Through the artwork, Bustos creates a non-linear narrative of the selected events, highlighting the visual resources used by more bloodthirsty fascist regimes. "Working with archives involves revisiting history and adopting a non-totalizing conception of it, seeing history as a narrative full of gaps, holes, omissions, and silenced parts, in other words, cracks. By re-signifying archival images and putting them into dialogue, the idea is to generate or induce another chain of associations, another historical narrative. It's crucial to use archival images because they are the remnants, the traces that remain. In my work, I make my own associations, but the juxtaposition technique enables the viewer to construct their own narrative. In the case of the videos, I approach them with a fascist aesthetic, but they may evoke other meanings for the viewer. The interpretation is not closed."

Graciela Sacco. Bocanada, 1993/2024. Cortesía de Marcos y Clara Garavelli

Graciela Sacco. Bocanada, 1993/2024. Cortesía de Marcos y Clara Garavelli

Graciela Sacco, (1956-2017), Rosario

Bocanada is a series composed of various works that Graciela Sacco began to create in 1993, in which she employs photographs showing close-ups of wide-open mouths. Using the early technique of heliography - which involves transferring an image onto a chemically treated surface exposed to light - the artist has reproduced these images in a variety of mediums ranging from installations to urban interventions. The first intervention took place in Rosario in 1993 when she pasted her images around a kitchen responsible for preparing food for the city's public schools. Workers were on strike, putting many children who relied on school meals as their only daily sustenance at risk. Graciela Sacco has carried out Bocanada interventions in cities around the world such as Buenos Aires, Sao Paulo, and New York. She has placed images on buildings, walls, and fences in public spaces, often working during election campaigns. Provocative and disarming, these wide-open mouths seem to invade the urban landscape, interfering with the messages of political campaign posters and other forms of propaganda, communicating feelings such as fear, outrage, or shock. These images carry strong political and social significance. For the artist, these images refer to issues of hunger and famine, but also more broadly to expressions of urgent need or an inability to communicate thoughts or desires.

Miguel Rothschild. Espectro, 2019-2021. Cortesía del artista y Ruth Benzacar galería de arte

Miguel Rothschild. Espectro, 2019-2021. Cortesía del artista y Ruth Benzacar galería de arte

Miguel Rothschild. Parcas sobre Buenos Aires, 2014. Cortesía del artista y Ruth Benzacar galería de arte

Miguel Rothschild. Parcas sobre Buenos Aires, 2014. Cortesía del artista y Ruth Benzacar galería de arte

Miguel Rothschild, 1963, Buenos Aires Miguel Rothschild's artistic work, rooted in photography, stands out for his ability to redefine the medium by integrating non-artistic elements. As he explains himself: "I like to use everyday materials like broken glass, fishing line, straws, or confetti, which, when taken out of their usual context, acquire an unsuspected dimension. Through intervention and confrontation with new images, I seek to question meanings: to illuminate the tragic or to endow the ordinary with deeper and more complex dimensions. It is an invitation to see with different eyes what surrounds us." In the photographs of the series Burned, moments of a forest fire are exhibited. The artist, in the manner of romantic landscapes in art history, uses photography as an allegory of that moment. If one looks closely at the works, they are pierced and burnt, giving the material depicted identity within the work, generating a dialogue between figure and materiality.

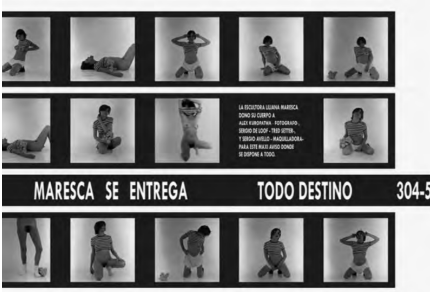

Liliana Maresca. Registro fotográfico: Alejandro Kuropatwa Maresca se entrega todo destino, 1993/2013. Colección Julio Cesár Crivelli

Liliana Maresca. Registro fotográfico: Alejandro Kuropatwa Maresca se entrega todo destino, 1993/2013. Colección Julio Cesár Crivelli

Liliana Maresca, 1951–1994, Buenos Aires The photographic performance "Maresca delivers herself every destiny," carried out by Liliana Maresca and published in issue number 8 of the monthly magazine "El Libertino" on October 8, 1993, consists of a sequence of 14 black and white photos depicting the artist in provocative poses. Developed across two pages, in addition to the woman's phone number, it included a text related to her status as an artist and listed the accomplices of the action: "The sculptor Liliana Maresca has donated her body to Alejandro Kuropatwa (photography), Sergio De Loof (wardrobe), and Sergio Avello (makeup) for this maxi advertisement in which she is willing to do anything." In the upper right margin of the page also appeared the names of the production's responsible parties: Fabulous Nobodies (a fictitious agency by Roberto Jacoby and Kiwi Sainz). To carry out and disseminate her photographic performance, Maresca chose a monthly magazine of erotic stories, attempting to transcend the boundaries of the singular artwork, surpass the temporal limits of exhibition, and broaden the scope of circulation and communication with the public: an artistic act that exists solely on printed paper and allowed her to become aware of the impact of the work, which "continues with the phone calls" from the public. "I'm talking about love, encounter, friendship with another through my work. I'm reclaiming the possibility of enjoying my body, which wasn't made for suffering but for pleasure. The work serves me to connect with my own eroticism."

Tomas Saraceno. Vuela con Pacha, hacia el Aeroceno, 2017- en curso. Cortesía del artista

Tomas Saraceno. Vuela con Pacha, hacia el Aeroceno, 2017- en curso. Cortesía del artista

Tomás Saraceno, 1973, San Miguel de Tucumán In Tomás Saraceno's work, art, science, engineering, and a commitment to the environment intertwine. On January 28, 2020, in Argentina, the Aerocene Pacha took off, becoming the first aircraft powered solely by air and sun. The choice of location was deliberate: "We are in the Salinas Grandes because, when the balloon flies over a white surface like this one of the salt flats, the sun reflecting on the ground increases lift capacity." The project reflects the relationship between the artist, the Aerocene community he founded, and the indigenous communities of Salinas Grandes and Laguna de Guayatayoc. Fly with Pacha expresses the artist's ecological stance with a particular reference to the local conflict caused by lithium extraction. Piloted by Argentine Leticia Noemí Márquez, the flying sculpture soared over natural environments carrying a message written on its surface by local populations: "Water and life are worth more than lithium." In "Arachne’s handwoven spider/web map," Saraceno revisits the spider with its web, a divine and relational symbol present in many of his works, and reworks it through the ancient technique of lace weaving. Between memory and tradition, the artist places respect for various local communities at the center of his research, involving 288 textile artisans from the Quebrada and the Puna de Jujuy in creating the web that characterizes the work.

“I heard about the ‘Anthropo not seen’ (instead of Anthropocene), meaning ‘the unseen’. It's very accurate because it's the part of society that is on the margins, what many don't want to see, like the indigenous peoples we met in Jujuy with the Aerocene project.”

Mariela Scafati. Barbecho, 2015. Colección privada

Mariela Scafati. Barbecho, 2015. Colección privada

Mariela Scafati. Marrón, 2015. Colección privada

Mariela Scafati. Marrón, 2015. Colección privada

Mariela Scafati, 1973, Punta Alta I crafted and dressed. I wrapped a painting with a sweatshirt and the hands of the girl I like with mine, because remember: I lost the sense of distance. And for this reason, I also did other things: hammered, printed, painted," reflects Mariela Scafati about her artworks. The versatility throughout her artistic production and the pursuit of color as a presence that gives body to the work are constants in the rich universe she proposes. From installations of colors that modify space to dressing her works, or the provocative queer posters, Scafati breaks the traditional limits of art. Her works, often devoid of frames, project from walls or intertwine with suspended objects, such as clothing, furniture, or ropes, in an intimate dialogue with the environment. In these two pieces, the large monochrome painting questions the way it is exhibited and also contemplated, flirting between abstraction and figuration, presenting itself as a landscape when naming it Buenos Aires. In contrast, in Barbecho, the artist covers the painting rescuing the gesture of care, shelter.

Juan Sorrentino. Cuerpo, sangre y hueso, 2020. Colección privada

Juan Sorrentino. Cuerpo, sangre y hueso, 2020. Colección privada

Juan Sorrentino, 1978, Resistencia Through sculpture, installations, videos, and performances, Juan Sorrentino explores the relationships established between sound and materials. The artist creates sensory experiences where sound is constantly questioned; in the piece "Body, Blood, and Bone," two glass cubes arranged on three charred woods contain a mixture of blood and bone dust. These substances rest on a base where a speaker emitting an extremely low-frequency sound is placed. This vibration agitates the particles of blood and dust, generating the formation of cloud layers in the surrounding environment. The artwork invites the viewer to reflect on the interaction between the physical and the auditory, as well as on the ephemeral nature of matter and the sensory experience it creates. “Sound is not limited to what the standard human ear can perceive, but also includes other visceral experiences. I approach the physical and symbolic properties of the landscape through encounters with the body, resulting in poetic gestures.”

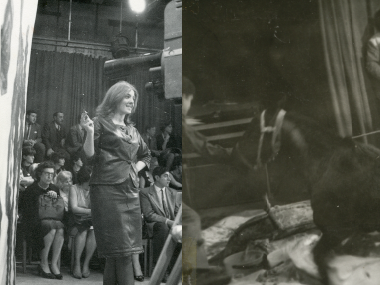

Marta Minujin. La cabalgata, 1964. Cortesía Archivo Marta Minujín

Marta Minujin. La cabalgata, 1964. Cortesía Archivo Marta Minujín

Marta Minujín, 1941, Buenos Aires The photographs document various scenes from the performance La cabalgata by Marta Minujín, which took place live on Channel 7 television in 1964, during the famous and massive program "La Campana de Cristal". In this segment, the artist orchestrated a series of unpredictable events: horses with paint buckets attached to their tails mingled with the audience, while chickens ran freely around the studio and bodybuilders popped balloons, all while taping two musicians together with adhesive tape. This artistic act challenges the established conventions in the media, highlighting the intersection between artistic expression and the media sphere through a chaotic and challenging narrative. "What I really enjoy is making a spectacle, being incorrect. I think it mobilizes people much more than behaving politely. Without insulting, without aggressing, without any of that; but breaking a bit of that ice that people have through education and upbringing." A friend and colleague of Alberto Greco, both in the 1960s questioned the work of museums, institutions, and galleries by challenging their rigid presentation of art and the place of artists. With an affinity for the concept of "art and life", both took their work to the public space, taking ownership of places and inviting and encouraging people to participate in art, to collaborate in the creation of the artwork.

Adrian Villar Rojas. Me sangra la nariz de la serie Me sangra la nariz+paisajismo+tareas+año 15.038, 2006. Cortesía del artista y Ruth Benzacar galería de arte

Adrian Villar Rojas. Me sangra la nariz de la serie Me sangra la nariz+paisajismo+tareas+año 15.038, 2006. Cortesía del artista y Ruth Benzacar galería de arte

Adrian Villar Rojas. Pedazos de las personas que amamos de la serie Me sangra la nariz+paisajismo+tareas+año 15.038, 2007. Cortesía del artista y Ruth Benzacar galería de arte

Adrian Villar Rojas. Pedazos de las personas que amamos de la serie Me sangra la nariz+paisajismo+tareas+año 15.038, 2007. Cortesía del artista y Ruth Benzacar galería de arte

Adrián Villar Rojas, 1980, Rosario Both works are part of a project by the artist Adrián Villar Rojas, titled My Nose is Bleeding, consisting of an extensive series of photographs taken over two years. They showcase the dedicated work in creating objects and installations that are the distinctive hallmark of his artistic identity. The artist appropriates vast spaces to juxtapose elements from nature, comics, and art history, often using clay to shape his own universe that reflects the present time. In his work, the presence of robots and science fiction characters intertwines with human figures, as seen in the portrait where a girl shares her space with a surrounding robotic structure. "With time, I realized that the only sculpture that interested me was our own species, which is entropic and degradable. (...) What I try to do is account for dynamic processes that exceed mere material production, and these 'sculptural objects' would be a kind of testimonies, always precarious and in mutation"

Pieces of the People We Love, also part of the series, alludes to the traditional still life in painting, where objects and materials are found within the space constructed by the artist using organic materials, being altered by the passage of time.