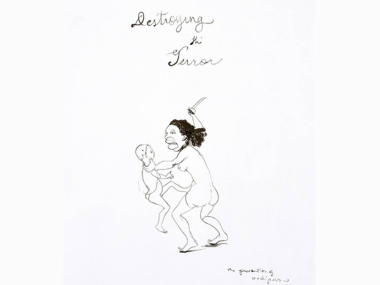

Untitled (Destroying the Terror), 1994

Untitled (Destroying the Terror), 1994

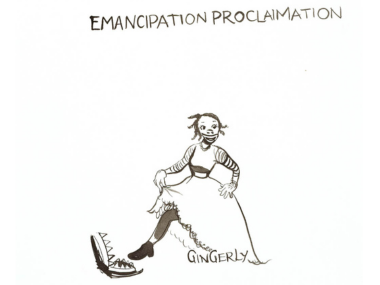

Untitled (Emancipation Proclaimation), 1994

Untitled (Emancipation Proclaimation), 1994

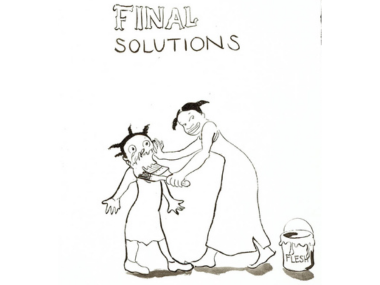

Untitled (Final Solutions), 1994

Untitled (Final Solutions), 1994

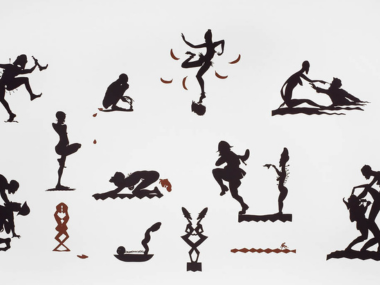

Untitled Drawings, 1994

Untitled (Destroying Terror) Walker Art Center Collection

Untitled (Emancipation Proclaimation)

Untitled (Final Solutions)

Untitled (Free Northern Girls)

Untitled (The Oppressor/Oppressed Paradigm)

Untitled (Words Too Heavy for My Head)

Kara Walker’s early drawings, preserved in the Walker Art Center’s collection and created in the late 1980s and early 1990s, reveal the combination of text and image, reinforcing the narratives that would remain central throughout her career. In them, Walker experiments with form, shadow, and contrast, outlining bodies and scenes charged with emotional and social tension.

The artist has noted that, being on paper and small in scale, these drawings allowed her a more direct and personal contact with her ideas, in a free and immediate way. More than simple sketches, they function as what she calls “visual laboratories,” where she develops her narrative and symbolic language, rehearsing the ideas and characters that would later populate her iconic black-silhouette installations. From these early works, one can discern the roots of her critical approach and how, from the outset, Walker challenged conventions of representation, creating images that are at once unsettling, poetic, and deeply reflective on African American history and collective memory.

Her interest in examining history was not to illustrate it literally, but rather to make the viewer feel the complexity, tension, and violence inherent in these stories. The accumulation of images creates a distinctive narrative, a personal mythology that draws from both the history of slavery and the history of art. Some pieces recall the caricatures of Daumier as well as the illustration of children’s tales, highlighting her ability to combine the grotesque, the poetic, and the narrative within a single artistic gesture.

Resurrection Story with Patrons, 2017

Resurrection Story with Patrons, 2017

Resurrection Story with Patrons, 2017

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Malloy Jenkins

In 2016, Kara Walker took part in an artist residency in Rome, a city she explored while studying its churches, museums, memorials, and works in public spaces. This period, influential in her artistic development, led her to reflect on the intersection of myth, martyrdom, and Christian iconography—often represented in medieval altarpieces—and to draw a parallel with the history of the United States.

Walker studied not only the formal qualities of these works but also the context of their creation—that is, the role of the State, the Church, and patrons in commissioning the pieces and their relationship with the artists who produced them. The triptych Resurrection Story with Patrons, 2017, is composed following the structure of medieval altarpieces and evokes the aesthetics of engravings and shadow play, recalling black paper cut-out silhouettes against a white background.

The central panel breaks with tradition: instead of saints or biblical scenes, it depicts the elevation of a colossal statue of a naked Black woman, lifted from the ground by smaller figures. The side panels present silhouettes of African American patrons. The female figure on the left holds a cross, a symbol of martyrdom and bodily suffering, while the male figure on the right stands before a wooden beam, which could allude to the ships used during migration. Both characters are simply dressed; the woman is bare-chested. These “patrons” display neither wealth, reputation, nor sanctity; instead, they are presented as martyrs.

Each panel functions as a visual laboratory, a space to explore characters, scenes, and power relations, while sustaining the critical and narrative force that characterizes her entire body of work.

Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions, 2004

Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions, 2004

Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions, 2004

8’ 49’’

Walker Art Center Collection

In the early 2000s, Walker adapted her paper silhouettes, transforming them into puppets and setting them in motion to create animated films that brought her art into a new dimension. Her first film, Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions, 2004, tells the story of a young enslaved woman seeking freedom through a series of vignettes, where each episode combines action, violence, and moral tension. As critic Hilton Als has noted, Walker constructs a kind of cinematic story on paper, in which the visual experience forces the viewer to confront historical brutality while also recognizing the formal beauty of the work. The combination of aesthetic attraction and narrative horror produces a critical tension: it is impossible to enjoy the piece without acknowledging the violence and oppression it represents.

The work emerged as the artist began engaging with early cinema, documentaries, and historical records—tools that shaped her narrative approach and enabled her to create sequences functioning as “mini paper films,” where each silhouette acts as an actor within a larger story.

This piece is key to understanding Walker’s practice as a crossroads between visual art, history, performance, and cinema, where historical narrative is reinterpreted through minimalist and powerful forms.

Endless Conundrum, An African Anonymous Adventuress, 2001

Endless Conundrum, An African Anonymous Adventuress, 2001

Endless Conundrum, An African Anonymous Adventuress, 2001

Walker Art Center Collection

In the eighteenth century, the use of cut silhouettes was a popular, economical, and highly impactful form of representation. Kara Walker takes up this technique to create large-scale works known as silhouettes, through which she investigates and reconstructs American history from a new perspective. The work Endless Conundrum, An African Anonymous Adventuress, 2001, was first presented the same year it was created, as part of an exhibition of her recent work at the Walker Art Center.

It is a visual narrative composed of various cut-out figures that, though seemingly separate, function together to document domestic scenes of relationships between Black and white people. In this way, Walker once again addresses the history of slavery. The title of the work, Endless Conundrum, refers to Constantin Brâncuși’s Endless Column (first version, 1918)—a gesture that functions as both homage and memorial, which Walker integrates into her own proposal.

According to scholar Yasmil Raymond, the work marks a shift in Walker’s artistic language, moving away from traditional silhouettes toward a multimedia narrative format. Raymond emphasizes that the piece explores the boundaries between fiction, history, and stereotype through the story of the “African anonymous adventuress,” combining humor, irony, and critical tension. The work prompts viewers to question historical and cultural constructions, highlights the tension between the public and the private, and reveals how African/African American identity is built from fragmentary narratives, with particular focus on the female figure.

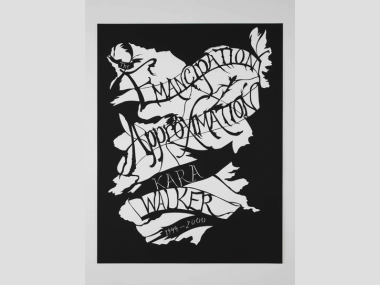

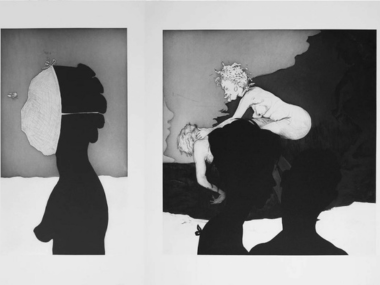

The Emancipation Approximation, 2000

The Emancipation Approximation, 2000

The Emancipation Approximation, 2000

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Malloy Jenkins

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by Abraham Lincoln in 1863, declared enslaved people in the rebel states to be free. Although it is remembered as an act of justice and liberty, in practice it did not immediately liberate all those enslaved and left many structures of racial and social oppression intact.

Kara Walker revisits this episode from a critical perspective, shifting attention away from Lincoln as hero and toward the violence, contradictions, and fantasies surrounding what was supposedly an act of liberation. The artist has said: “I didn’t want a clean, easy story about freedom. I wanted to show how messy and violent emancipation really was.”

The series is composed of black-and-white screenprinted panels. It was first presented at the Carnegie International (1999/2000) and later exhibited at the Walker Art Center (2001), where it provoked significant debate due to the starkness of its imagery in contrast to the official history of freedom in the United States. Critic David Frankel wrote at the time: “The individual prints of The Emancipation Approximation coalesce into a tableau that is as challenging as it is beautiful, and as intricate as it appears simple.”

With its black silhouettes against white grounds, and white or gray silhouettes against black, Walker stages scenes where the decorative coexists with the violent: bodies subjected, sexualized, and inscribed with relations of power. She questions the heroic narratives of official history, showing that emancipation was fraught with contradictions and that inequalities persist in contemporary life.

Like a literary or cinematic story, the scenes unfold without offering a closed beginning or end. Walker builds a fragmented and ambiguous narrative that compels viewers to complete the story in their own imagination. That ambiguity—between beauty and horror, between freedom and violence—is what makes the work so unsettling and so relevant today.

Sugar Baby or the Marvelous Sugar Baby an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant, 2014

Sugar Baby or the Marvelous Sugar Baby an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant, 2014

Sugar Baby or the Marvelous Sugar Baby an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant, 2014

Built over several weeks inside the former Domino Sugar Factory—a historic industrial complex in Brooklyn on the verge of demolition—the monumental installation A Subtlety: Or… the Marvelous Sugar Baby…, 2014 recalls that sugar, a symbol of pleasure and consumption, was once the driving force of vast plantations in the Caribbean and North America where millions of enslaved Africans were forced to work.

The title condenses this ambivalence. In medieval Europe, a “subtlety” was a sugar sculpture served at aristocratic banquets to display wealth and power. Walker reclaims the term ironically, underscoring how refined sweetness conceals a history of violence. At the same time, A Subtlety: Or… the Marvelous Sugar Baby… alludes both to the fragility of a figure modeled in sugar and to the popular use of the term to refer to young women financially supported by older men. This reference introduces the dimension of sexualization and inequality historically imposed upon female bodies.

At its center, a sphinx more than 10 meters tall coated in white sugar embodies this tension between monumentality and stereotype. Its reference to Egyptian sphinxes—symbols of power and eternity—contrasts with the perishable materiality of sugar, which melts and decays. Instead of guarding sacred temples, this sphinx protects an erased memory: that of the enslaved people who made the sugar economy possible.

In form, Walker grants monumentality to the figure of the mammy, deeply rooted in U.S. visual culture. Historically represented as a smiling, asexual caretaker with an exaggerated, utilitarian body, the mammy functioned as a caricature designed to naturalize and justify the domestic exploitation of African American women. Walker amplifies certain features—oversized breasts and buttocks, monumental pelvis, fleshy lips, headscarf—monumentalizing the figure and confronting both historical violence and its affective centrality in everyday life.

Surrounding the sphinx, sculptures of children cast in molasses carry fruits and baskets, evoking the forced labor of plantations and sugar refining. The progressive deterioration of the materials intensified the ephemeral dimension of the work, while the imminent collapse of the factory reinforced the sense of loss and erasure. About the work, Kara Walker stated: “The main reason for refining sugar is to make it white. Even the idea of becoming ‘refined’ seems to coincide with the way the West approaches the world.”

A Subtlety: Or… the Marvelous Sugar Baby… was a mass event, visited by more than 100,000 people, confronting viewers with the historical violence concealed behind an apparently innocent product and with the urban ruins marked by gentrification.

An Unpeopled Land in Uncharted Waters, 2010

An Unpeopled Land in Uncharted Waters, 2010

An Unpeopled Land in Uncharted Waters, 2010

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Malloy Jenkins

no world

beacon (after R.G.)

savant

the secret sharerer

dread

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Malloy Jenkins

An Unpeopled Land in Uncharted Waters, 2010, is a series of six prints by Kara Walker in which she employs etching, aquatint, sugar-lift, spit-bite, and drypoint to construct images that are at once fragmentary and monumental. The edition sold out quickly and today belongs to the collections of major international museums.

The title of the series—as often happens in Walker’s work—refers to the transatlantic voyage of enslaved people toward a “New World,” which, in her view, can also be read as a “No world”: a territory presented as uninhabited and, at the same time, an uncertain destination yet to be named. The paradox is expressed on two levels: on the one hand, the idea of America as an empty space without inhabitants; on the other, the experience of Africans cast into uncharted waters, with no certainty of what they would encounter. This tension is reflected in the central image, where hands emerge to hold a boat above dark waters, while from the shore ambiguous figures look on, leaving us uncertain whether they are those departing or those arriving. The series unfolds as a sequence of fragments evoking different moments of that journey, pausing on intimate aspects rarely represented of the experience and the cultural encounter that took place there.

From the sixteenth century until its abolition in the nineteenth, the slave trade from Africa was a constant. Born to sustain colonial economies based on sugar, cotton, and tobacco plantations in lands deemed vacant, this system transformed people into commodities and transported them under inhumane conditions across the Atlantic. Although progressively abolished during the nineteenth century, slavery left a legacy of dispossession that endures to this day.

The series also acquires an unsettling resonance in the present, as it relates to the journeys of African migrants crossing the Mediterranean toward Europe. As in the transatlantic trade, new generations face uncertain seas, precarious voyages, and the possibility of vanishing in “uncharted” waters. Walker’s work thus reminds us that history is not closed: the same logics of displacement and the search for freedom persist in new forms, compelling us to acknowledge the ongoing presence of injustice in contemporary migratory experience.

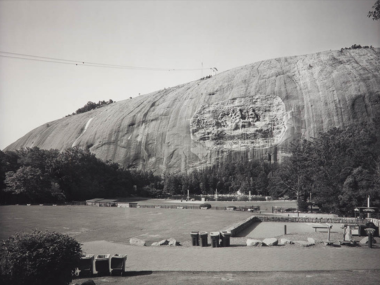

The Stone Mountain Dr. Martin Luther King referred to in his famous I Have a Dream speech of 1963 (with monument to the Confederacy completed in 1972), 2015

The Stone Mountain Dr. Martin Luther King referred to in his famous I Have a Dream speech of 1963 (with monument to the Confederacy completed in 1972), 2015

The Stone Mountain Dr. Martin Luther King referred to in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech of 1963 (with monument to the Confederacy completed in 1972), 2015

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Malloy Jenkins

In his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, Martin Luther King invoked the summit of Stone Mountain as a site from which freedom should resound. Yet, on that very mountain, work was underway on a massive relief exalting white leaders of the slaveholding South. The monument was not completed until 1972, nearly a decade after King’s call for equality, laying bare the paradox between his dream and the persistence of public monuments that glorify the cruelty embodied by those figures.

For Kara Walker, Stone Mountain is not an abstract place: she grew up nearby after her family relocated to Georgia in the 1970s. The silhouette of the monument was part of the landscape of her childhood—an imposing reminder of historical violence and an official memory that excluded African Americans. By photographing the mountain, Walker does not seek to celebrate it, but rather to appropriate that image and give form and place to King’s discourse.

The work also marks the beginning of a new series of investigations into the political and symbolic function of monuments. Walker interrogates how they are erected, whom they celebrate, and what narratives they silence, displacing the monumental language onto other media—photography, watercolor, cut paper—in order to expose the fragility of these images of power and open them up to critical readings.

The existence of the monument has been the subject of debate and conflict, especially in 2015, following the Charleston massacre at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church—the oldest African American church in the South of the United States—where nine people were killed by a white gunman. Walker cites this event as a catalyst for rethinking the meaning of Stone Mountain, while her work also engages with the traditions of American landscape photography and painting.

Monuments for the Late United States, 2016

Monuments for the Late United States, 2016

Monuments for the Late United States, 2016

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Malloy Jenkins

The series of watercolors deepens Walker’s reflections on monuments and the roles they play in contemporary life. The artist experiments with different typologies, ranging from the pyramid and the monolith to more abstract forms that evoke organic universes present in diverse cultures. The question of the monument’s form is also a question of memory and of the narratives sedimented in history. Walker reveals how monuments—regardless of their typology—shape lived experiences and function as testimony to an official history. The absence or presence of figures in these works underscores the ways in which memory is renewed and made visible.

Fons Americanus, 2019

Fons Americanus, 2019

Fons Americanus, 2019

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Malloy Jenkins

In 2019, Tate Modern in London invited Kara Walker to intervene in the Turbine Hall, an emblematic museum space dedicated to unique large-scale commissions conceived to engage both with its architectural monumentality and with the massive public that enters freely. There she presented Fons Americanus (2019), a thirteen-meter-high fountain inspired by the Victoria Memorial, erected in front of Buckingham Palace to commemorate Queen Victoria, a figure associated with the height of the British Empire and its global colonizing policies.