Christo in his studio working for The Floating Piers. New York, November 2015.

Christo in his studio working for The Floating Piers. New York, November 2015.

Christo in his studio. New York City, 1965. Ph: Ugo Mulas � Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation and Ugo Mulas Heirs

Christo in his studio. New York City, 1965. Ph: Ugo Mulas � Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation and Ugo Mulas Heirs

Christo in his studio. New York, 1983. Ph: Wolfgang Volz. � Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

Christo in his studio. New York, 1983. Ph: Wolfgang Volz. � Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

It’s with a drawing that the journey begins

Lorenza Giovanelli, curator

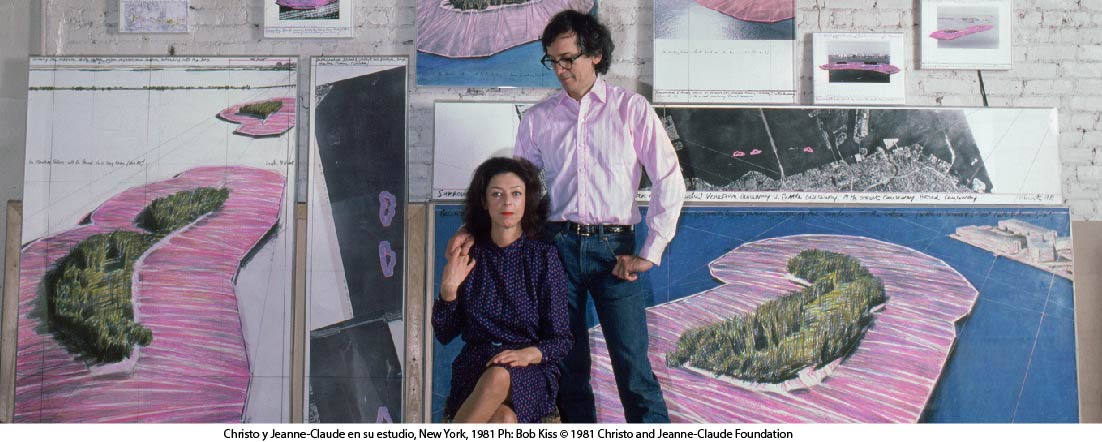

In his artistic collaboration with his wife and lifelong partner Jeanne-Claude—began in 1961 and officially announced in 1994, subverting the clichéd roles of a still conservative and rather chauvinist art scene—Christo developed monumental and temporary projects around the world based on a new model of self-financing, free and open to the public, that earned Christo and Jeanne-Claude a unique place in the history of art.

(…)

Born in 1935 in Gabrovo, at the foot of the central Balkan Mountains in Bulgaria, he was a very quiet and reserved child. He would speak little, often delegating the transmission of his thoughts to his older brother Anani, playfellow and lifelong confidant.

(…)

In a Bulgaria where art textbooks were either obsolete or censored by the oppressive Stalinist regime, Christo developed little knowledge of the avant-gardes. Art history would abruptly end with the early works of Edouard Manet, and the only contact he had with the 20th century expression was the Russian avant-garde, thanks to his mother.

However, not being initiated to the modern Western art had a positive side: Christo had more time to develop his talent by engaging in the traditional means of drawing and painting, and in particular, realistic portraiture. Between 1947 and 1956, he did countless portraits that show a confident hand, perfectly at ease with working fast and doing so as naturally as breathing. Farmers, factory workers, friends, family members, and acquaintances were the subjects of his restless visual investigation of reality.

Those drawings, often collected in small sketch books, represent cumulatively the precious paper trail of Christo’s last decade in Bulgaria.

Being admitted at the Sofia Academy of Fine Arts meant the world to Christo. He used all the resources he had in order to achieve what he thought would be a life-changing experience.

(…)

Tired of what he called an “insincere attitude towards art,” in 1956 Christo left Sofia full of expectations and no regrets. His rebirth stared in Prague, where he finally felt free to draw.

Christo Javacheff, Untitled (Still Life), 1950. Óleo sobre papel, 50 x 70 cm. Colección Matthias Koddenberg, Munster, Alemania

Christo Javacheff, Untitled (Still Life), 1950. Óleo sobre papel, 50 x 70 cm. Colección Matthias Koddenberg, Munster, Alemania

“I feel reborn... For the last two weeks, I have been unusually happy and going through so many things in order to draw. [...] Unbelievable things have happened. I have never talked so openly. [...] Art is discovery, innovation, a profound mission to find the most contemporary, novel expression... Art is, more than anything else in life, beauty. Art creates what no one has seen before...To be a discoverer requires more than reading books—one has to feel the pulse of time.”

When the Hungarian Revolution broke out, Prague was no longer a safe place to be. A long and grueling voyage led him first to Vienna in January, 1957; then to Geneva in October; and finally, on March 1, 1958, he reached Paris, where he was drawn by the city’s artistic aura. The seven years he spent in Paris, from 1958 to 1964, played a seminal role in his artistic career. In this short but extremely intense period, free from any imposed precepts and taboos, he became involved with the French and international avant-garde, developing friendships with the Portuguese artists René Bertholo and Lourdes Castro, and the KWY circle, frequenting the Nouveaux Réalistes and becoming inspired by a progressive art scene where he could finally express himself freely.

(…)

The appropriation and manipulation of everyday objects soon became his primal interest to the point of obsession. His approach was absolutely radical. He was more concerned with the texture and shape than with the content. While they were concealed with the wrapping, as if protected by a second skin, those objects were reinstated, suspended from their duties without precluding the status quo prior to the artistic action, guided into that nomadic transitory state that would become the quintessence of his large-scale projects.

Those early works were the result of instinctive artistic experiments and wouldn’t require any kind of planning or preparation. Christo would confront himself directly with the object. His approach was very direct and physical and not mediated by sketches or models. The direction where his creative process would take him was already clear, and even though his formal and visual vocabulary was already in place, his work soon began to evolve. His works increased in size, became more complex, and reflected a closer relationship with space. The turning point came in 1964, after he and Jeanne-Claude had moved to New York. Space and architecture became more and more predominant in Christo’s work, to the point where his own approach to the artistic practice changed. “At the Academy of Fine Arts, I studied architecture and I loved this discipline. I think it shows in my work. At over 80 years of age, I look at our work with Jeanne-Claude and I see that architecture is very present. It makes me think differently than painting or sculpture.”

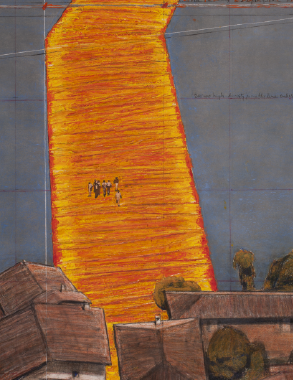

Temporary projects set in urban or natural contexts required long preparation and a more technical approach, less visceral than the early wrappings or pictorial experimentations. Christo re-engaged with the favored medium of his youth: drawing.

Drawing began to play a key role in both the genesis and the final complexity of his monumental projects. “Drawing is very important. It gives me energy,” he would always say. Nestled in the privacy of his studio, he could spend countless hours working alone, with no assistants. His hands touching the paper, the sound of the graphite shaping a symphony of lines, amplified by a solid silence, were occasionally interrupted by the feeble noises of the old Howard Street building stretching its bones. In drawing, which he practiced joyfully and relentlessly until his death, he showed the same freedom and daring as in his titanic projects.

“Works on paper can be a combination of photographs, fragments of other projects, technical information... [...] The drawings reflect the evolution of the project. It doesn’t emerge from my thoughts ‘fully equipped’.”

Flawlessly mastering the rules for creating academic art, he bent them to create highly inventive collages in which traditional materials (pencil, charcoal, pastel) naturally blended with unorthodox ones (industrial paint, plastic, fabric, string, masking tape...) as if they were a concerto of perfectly intonated voices. From the “skeletal and problematic” initial sketches to the hyper detailed and ultra-descriptive final works, all drawings—or “preparatory works,” as Christo would define them—are part of what Christo called the “growing process.” Complex and long, often very long, the growing process consisted of negotiations with administrators and government officials to obtain permissions, discussions with residents and local associations to calm fears and counter objections, and consulting with engineers and craftsmen on the project’s technical development and implementation. It allowed him to adjust and refine his ideas, which would influence his drawing and, in turn, have a powerful impact on the project’s conception.

As a “big advocate of aesthetics,” composition, rhythm, color, and proportions were the foundations of Christo’s perceptual knowledge. “Drawing helps me think, and the last drawing is the closest to reality because it has benefitted from all the information, by the real relationships between things, by all the reflection. With it, the vision crystallizes.” The interaction between the technical elaboration of a project and the development of his preparatory works is essential to grasping the evolution in Christo’s drawings. By working simultaneously on several different projects, and by constantly going back and forth between drawings and collages from one series or another, he nourished and refined his vision. His final preparatory work predicted the executed project so accurately that they appeared to mirror its definitive state. As a path to reality, drawings became the history and the archive of each project. It’s with a drawing that the journey begins.

Photography played a prominent role in his preparatory works too. Images by Harry Shunk, Gianfranco Gorgoni and, since 1971, by Wolfgang Volz, represent both an invaluable archive documenting the history of their projects and a collection of images that were always available to Christo. Painted over, used in collages, or cut up, they helped enhance his vision, and he integrated them into his smaller-scale preliminary sketches as well as into the final drawings for each project. The journey began in the studio and ends at the project’s site. His original artwork tracked that path, essential for the engineers in building the project, and essential to explain to the public that would see it what it was about and how it would temporarily transform the space.

(…)

The journey began in the studio and ends at the project’s site. His original artwork tracked that path, essential for the engineers in building the project, and essential to explain to the public that would see it what it was about and how it would temporarily transform the space.

Described by Christo and Jeanne-Claude themselves as “irrational, irresponsible and useless” their entirely self-funded projects have often been marked as senseless enterprises.

(…)

Far from pure conceptual art where long thinking periods would result in no action, what Christo and Jeanne-Claude offered us through their projects was, instead, experiences of reality. Christo would often remark how “so many works of art are only illustrations, decorations, ideology,” the basis of what he mostly rejected his whole life: propaganda. Their interventions were nourished with true feelings and human interaction. Their “gentle disturbances” had the thunderous voice of freedom and the fragility and tenderness of what is not destined to last. They were a form of truth in action, they were real experiences, each one profoundly different from the other. Each time Christo and Jeanne-Claude began to work on a project, they started fresh, ready to discover what it would become and how it would evolve.

Christo en su estudio, abril 2012. Ph: Wolfgang Volz

Christo en su estudio, abril 2012. Ph: Wolfgang Volz

(…)

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work has always been more than making an object: The artwork was not just the two-week-long installation; it was the people, the meetings, the drawings, the surveys, the leasing, the engineering, the construction, the politics, the hearings, the assembling, and every single thing that contributed to its final complexity. In this sense and as artists agree, it is “environmental art.” The notion of environment emerges from the circumstances, objects, or conditions by which one is surrounded; the complex physical, chemical, and biological factors that act upon an organism or a community and ultimately determine its form and survival; and the human awareness of the passing of time and of the effects of this passing on the context humanity lives in. This definition perfectly reflects the primary medium that constitutes Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s projects: humanity. They are created by people, for people, and in places where people live. Their own existence echoes the intrinsic condition of human nature, transience, making their work pure expressions of profound humanism.

Giovanelli, Lorenza, fragments from the text “The journey begins with a drawing”, in AA.VV. Christo and Jeanne-Claude. In Uruguay, catalog of the exhibition, Uruguay, Atchugarry Museum of Contemporary Art, January 2021, pp.19-34.

Hommage � l�tranger - IX, 2020. Oil on cardboard. 31,5 x 24,5 cm. Private Collection

Hommage � l�tranger - IX, 2020. Oil on cardboard. 31,5 x 24,5 cm. Private Collection

The Floating Piers, Project for Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014. Collage. 77,5 x 66,6 cm y 77,7 x 30,5 cm Ph: Andr� Grossmann � 2015 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

The Floating Piers, Project for Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014. Collage. 77,5 x 66,6 cm y 77,7 x 30,5 cm Ph: Andr� Grossmann � 2015 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

Memories of my friend

Jorge Helft

(Fragmentos)

How much has Christo’s artistic career evolved in recent years! A man who packed objects now engages with monuments and natural settings.

We are in 1971, and he is thinking of concealing an entire valley in the state of Colorado with a gigantic orange curtain, an immense canvas to be installed by a team of workers under his direction.

My friend, the art historian and critic Pierre Restany, writes down the exact location in his notebook: 35 degrees 48 minutes north latitude, 107 degrees 45 minutes west longitude; altitude: 5,000 feet; total surface area of the curtain: 200,200 square meters. For this venture, the artist has created the Valley Curtain Corporation. Six museums, eighteen private collectors and twelve art galleries have bought shares, which were comprised by art-works related to the project.

(…)

As with each project, the operation that consists in carrying out the project is the very essence of the work. The self-financing system that Christo has created for this project is unique in art history. This draws Pierre Restany’s admiration. The undertaking, as those that will follow, shows the author’s freedom and imagination.

(…)

We are now in 1976, five years later. Christo has undertaken a mammoth project, Running Fence, from the vineyards of Sonoma to the ocean in Marin County. The artist builds a flexible fence: It is a sinuous nylon cloth that covers the ground drop down to the ocean. A real army of workers helped by trucks and bulldozers is setting up this enormous curtain waved by the wind. Once again, Pierre Restany cannot hide his amazement. What a long way has our artist travelled since the moment when he blocked the narrow Rue Visconti with empty iron drums! He is bewildered by the artistic importance of this gesture.

This gigantic fence between two symbols, ocean and highways, is generating a lot controversy.

(…)

Christo is used to that. He knows that his spectacular project is in harmony with reality and that he cannot be accused of anything being forced. As he likes to point out, “It is only a very beautiful thing.” Running Fence crosses several private farms, a small town, a highway, to finally disappear into the ocean, north of San Francisco.

During the 14-day exhibition, 500,000 people will see it. Christo and Jeanne-Claude, as always, have decided to wage battle on several fronts: material, financial, and legal ones.

Pierre Restany strolls around watching the 2,500 white nylon pieces outstretched on steel poles secured to the ground by tens of thousands of earth anchors. A titanic job, fragile moments of beauty that the critic relishes and enjoys. He knows that this project is a pragmatic confirmation of his theory: “The other side of art.” An authentic contemporary artwork, it holds an undeniable interest within the economic world that has been quickly grasped by those responsible for the banks managers and heads of committees who rejected it at first: the sudden increase of tourism in the area, added to the temporary work force employment provided by Christo, is a blessing. Art helping economy. Art totally integrated to society. Art sweeping all obstacles.

The Gates, Project for Central Park, New York, 2002. Ph: Wolfgang Volz

(…)

I was convinced that Christo was a great artist from the very first moment. Later, Restany added “and Jeanne-Claude” due to the significant role she played by managing the projects and all the financial aspects that made it possible for them to be carried out. As I said before, I knew that Christo was one of the great artists of his time, a time that was also mine. I’m certain he has impacted art in such a categorical way that he will continue to be influential when our era is subject to scrutiny many years from now.

(…)

I must start by mentioning a few figures around the incredible dimensions of these art works. 430 workers and more than 600,000 square meters of floating pink polypropylene in Miami; 100,000 square meters of polypropylene fabric with an aluminum surface and 15,6 kilometers of blue polypropylene rope to wrap the Reichstag; and 7,503 free hanging saffron fabric panels suspended on just as many gates installed on 37 kilometers of walkways in Central Park for The Gates. In addition, after having been on display for only two weeks, not the slightest trace of what had been there remained. These artworks had never had owners. Only the sketches, drawings and photographs of the events remain.

This chapter of artistic creativity ends with L ́Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped. The world’s artistic history now includes works that went beyond what was conceivable only with the purpose of shocking us; what Duchamp described as “eco aesthetic.” Fifty-two years of history of art. An era of unique creative richness, not only in terms of artistic production but also in terms of variety.

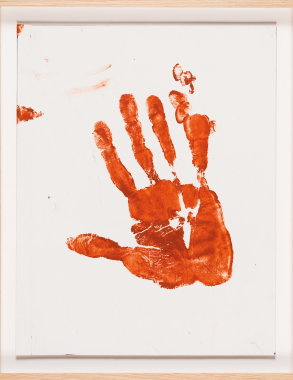

With pleasure, surrounded by indelible memories, carried by the much-valued moments of friendship, I stay at home looking at the last small creation made by Christo before he died: A little work on paper, 31 × 24 cm, that means so much to me, especially because of our long friendship.

Helft, Jorge, fragments from the text “Recuerdos de mi amigo”, in AA.VV. Christo and Jeanne-Claude. In Uruguay, catalog of the exhibition, Uruguay, Atchugarry Museum of Contemporary Art, January 2021, pp.13-17