The exhibition

Originating in the Peruvian Andes, the Tahuantinsuyo—meaning "the four parts" in Quechua, referring to the four regions that comprised it—reached its peak around the 15th century. Its influence extended over the present-day territories of Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, and Argentina, leaving a deep mark on the societies they conquered along the way. Among its most notable features were the meticulous organization of its domains under an advanced social, political, and economic structure, as well as their prowess as architects and engineers. They were responsible for building majestic cities and, among other feats, a network of roads called the Qhapaq Ñan, which connected landscapes and tributary towns of the emperor and has been declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

“The Incas: Beyond an Empire” is presented in Buenos Aires, developed into thematic sections. In Room 1, dedicated to the Origins and Formation of Tahuantinsuyo, the exhibition explores the origin of the Incas, which had long been proposed based on mythical stories collected during the colonial period. These origins were conceived as the result of a migration of foreign populations from the Altiplano or neighboring regions to Cuzco, where the founding ancestors came from. The historicity of these accounts has been questioned through archaeological investigations, which reveal a long process of development by local populations in the Cuzco valley prior to the formation of Tahuantinsuyo.

By the early 15th century, the Incas had already consolidated as the dominant group in the Cuzco region. From then on, an expansion process began, eventually reaching vast territories in the Andes. Tahuantinsuyo incorporated various populations, each with its own customs and traditions. This political formation relied on a combination of military, economic, social, and ideological strategies, implemented based on dynamics established with the elites of each locality.

Room 2 explores sections related to the organization and administration of the empire, land production, identity through clothing, and rituals and offerings. Managing such a vast and diverse structure was only possible through an organized system to control resources and population. In Tahuantinsuyo, there were about 80 provinces or huamani, each with around 20,000 to 30,000 families, who contributed labor as a form of tribute. This allowed for major public works such as the construction of buildings and roads, or the implementation of agricultural projects, overseen by state officials. In this administrative system, the use of quipus was crucial. In the form of knotted cords, the quipu was the main system of record-keeping in the Andes. Like in other ancient societies, its origin was linked to the first forms of imperial organization. These are simple structures with hanging cords wound with colored threads and simple knots. While most Inca quipus recorded numerical data, we know that some also stored narrative information such as stories and genealogies.

It is estimated that there were up to two million hectares of arable land in Tahuantinsuyo. These were achieved over centuries through hydraulic works and the construction of agricultural terraces on the slopes of mountains. Production was ensured not only by proper labor and technology management but also by the performance of ceremonies dedicated to promoting the fertility of the land.

Rituals were the main form of direct communication with the forces that animated life in the world. Many of these practices were assimilated by the Incas and continued, with some transformations, even after the Colonial period. In this section, we display some objects that, by their nature or the energy they transmitted, played active roles in religious life, both in the domestic and state spheres.

A series of garments and ornaments allowed for the identification of the various roles fulfilled by some Inca officials, a strategic workforce for the development of the state. Below the Sapa Inca and the coya were soldiers and administrators of different ranks, as well as mamaconas and acllas. Several of these figures and their attributes were recorded in the illustrated chronicles of the late 16th century as part of a memory aimed at attesting to their existence.

Room 3 focuses on the landscape, architecture, and territory. With its emblematic design and particular way of transforming and integrating with the landscape, Inca architecture made the state's presence visible across a vast territory. While constructions were characterized by marked simplicity, elite buildings are easily recognizable by their use of finely polished stones and trapezoidal shapes. From agricultural terraces to royal estates, the Incas knew how to adapt architecture to the topography like no other Andean culture. By 1520, when Tahuantinsuyo reached its greatest extent, a state-controlled road system, the Qhapaq Ñan, spanned the Andes and Altiplano, connecting the empire's various populations.

The visual language of the Incas is distinguished by a break from previous traditions in the Andes. While most representations have been described as geometric and abstract—possibly inspired by textile patterns—we also find some figurative images of marked simplicity, and others that combine color patterns. For the Incas, however, the process of creating these objects, as well as the materials used, were more important than their superficial appearance, as the essence of the object was prioritized in their worldview.

In Argentine territory, various ethnohistorical sources place the Incas' arrival between 1471 and 1493. Contemporary audiovisual resources present archaeological sites discovered in three of the seven provinces that were part of the empire. The sites of Pucará de Tilcara (Jujuy), La Paya and Llullaillaco (Salta), Aconquija and Shincal de Quimivil (both in Catamarca) are exhibited, allowing the public to appreciate the different settings where the encounter and dialogue with local communities took place.

In Room 4, A Breaking Point, works related to the colonial period are presented. Since Francisco Pizarro and his troops made contact with Tahuantinsuyo, violence forged the foundations of a new order in the Andes. The initial milestone of this process would be the capture and execution of the Inca Atahualpa in 1532. However, dismantling that empire required not only the participation of thousands of natives but also negotiating power shares with certain indigenous sectors.

In turn, the term Tahuantinsuyo would be replaced by that of Peru, a name that would eventually acquire different meanings as colonial power consolidated. The very memory of pre-Hispanic times was transformed to meet the needs of a different society and the imposition of Western artistic languages and techniques. This created a permanent tension between rupture and continuity with the past.

Los incas. Más allá de un imperio

By Cecilia Pardo, Ricardo Kusunoki, and Julio Rucabado / Curators

Around six hundred years ago, the Andean region witnessed the birth and development of one of the most important civilizations of the ancient world. Its main actors were the Incas.

Through the study of material culture and written sources, The Incas: Beyond an Empire explores Inca culture, from its origins in Cuzco and the formation of a vast empire—Tahuantinsuyo—to its integration into a new colonial order. Additionally, it examines the Inca legacy in contemporary Peruvian society through art, design, and living culture.

A representative selection of objects from various public and private collections in the country serves as the foundation to outline narratives about key chapters of this great history, primarily addressing a crucial question: Who were the Incas? This inquiry leads us to revisit important aspects of this culture, such as their political and administrative management, main expansion strategies, their unique conception of landscape and territory, and their worldview. The project also highlights the many reinventions of the Incas, starting from the colonial period, expressed through various media including painting, engraving, and photography.

The breaks and continuities posed throughout such an extensive historical timeline are presented in this exhibition as spaces that invite us to rethink certain preconceptions about the origin, development, and end of a phenomenon that has resisted fading from our memory, and whose legacy continues to live on in all of us today.

Colonial Temprano (ca. 1500 1600). Quipu num�rico

Colonial Temprano (ca. 1500 1600). Quipu num�rico

Origins and Formation of the Tahuantinsuyo

The origin of the Incas has long been proposed based on mythical accounts collected during the Colonial period. These beginnings were conceived as the result of a migration of foreign populations from the Altiplano or from regions neighboring Cuzco, from which the founding ancestors were believed to have come. The historicity of these accounts has been questioned by archaeological research, which indicates a long process of development among local populations in the Cuzco Valley prior to the formation of the Tahuantinsuyo.

Towards the early fifteenth century, the Incas had consolidated their position as the dominant group in the Cuzco region. From that point on, they began a process of expansion that would eventually cover a vast territory in the Andes. The Tahuantinsuyo incorporated a number of different populations, each with their own customs and traditions. This political entity was based on a combination of military, economic, social, and ideological strategies, implemented based on the dynamics established with the elites of each locality.

Tiwanaku (600 1000). Vaso con dos bandas en la zona media del cuerpo

Tiwanaku (600 1000). Vaso con dos bandas en la zona media del cuerpo

The Tiwanaku and Wari cultures, which emerged in the southern Andean region during the first millennium of our era, have been associated with the origins of the Incas. This selection of vessels highlights the formal relationships between Tiwanaku, Wari, and Inca styles. The shapes and decorative elements emphasize the idea of a certain cultural continuity, which seems to be explained by the widespread distribution of this type of vessels and the ceremonial practices in which they were used, within a context of interaction between southern Andean and highland societies.

Wari (600 1000). Escultura que representa a un personaje con t�nica y gorro de cuatro puntas

Wari (600 1000). Escultura que representa a un personaje con t�nica y gorro de cuatro puntas

Between the 7th and 10th centuries AD, the Wari forged the first empire in the Andes. As they expanded, they settled in the Cuzco region, spreading Quechua as a common language, as well as a series of technological and cultural advancements that would later be adopted by the Incas. Noteworthy are the knotted cord system (quipu) for recording information, the production of textiles using tapestry techniques, and the ritual use of a particular style of vessels for toasting. The image of the Wari lords was depicted on various mediums. They wore tunics and four-cornered hats, symbols of prestige and expressions of their political and religious power. The image of the Wari warrior shows that they wore shirts decorated with a checkered pattern, similar to the piece presented here.

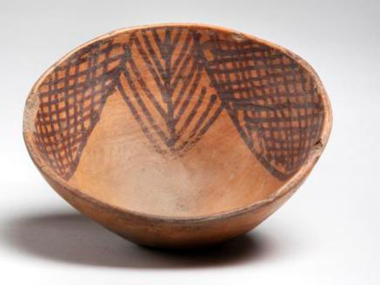

Killke (1000 1400). Plato con dise�os geom�tricos

Killke (1000 1400). Plato con dise�os geom�tricos

Between the 12th and 15th centuries, prior to the development of the Inca empire, various groups inhabited the Cuzco Valley. Such is the case of the Ayarmacas, the Antas, and the Cuzcos, the latter of whom would later be known as Incas. Archaeologically, this group is linked to a distinctive ceramic style called Killke. This type of pottery, characterized by geometric designs on cream backgrounds, has been found at sites such as Sacsayhuamán and the Coricancha in Cuzco, as well as in the provinces of Paruro and Lucre.

Inca (1500 1600). Uncu con dise�os cuadrangulares de diversos colores

Inca (1500 1600). Uncu con dise�os cuadrangulares de diversos colores

Traditionally, the consolidation of the Tahuantinsuyo has been associated with the deeds and achievements of three great rulers: Pachacútec, Túpac Yupanqui, and Huayna Cápac. However, a closer reading of written sources reveals that the success of this organization also depended on various agents in the service of the state, many of whom were linked through blood ties, marriage alliances, and a system of privileges granted by the leader. This elite, primarily male, is known from colonial references as “Incas.” They could be identified by their clothing and ornaments, particularly the use of large earspools.

Colonial Temprano (ca. 1500 1600). Quipu num�rico

Colonial Temprano (ca. 1500 1600). Quipu num�rico

Organization and Administration

Managing such a vast and diverse enterprise was only possible through a structure organized to control the population and its resources. In the Tahuantinsuyo, there were around eighty provinces or huamani, each with about 20,000 to 30,000 families who contributed their labor as a form of taxation. This allowed for large-scale public works, such as the construction of buildings and roads, or the implementation of agricultural projects, supervised by State officials. In this administrative system, the use of quipu played a critical role.

In the form of knotted cords, quipu served as the primary system for recording information in the Andes. As in other ancient societies, its origin was linked to the first forms of imperial organization. They are simple structures with hanging cords wrapped in coloured threads and basic knots. While most Inca quipus recorded numerical data, we know that some also stored narrative information such as stories and genealogies.

Inca (1400 - 1532). Quipu num�rico

Inca (1400 - 1532). Quipu num�rico

After the conquest, quipus were incorporated into the colonial system, primarily used for recording confessions and collecting tributes for the Church. The specimen displayed here is part of a set of six quipus from the Áncash region, in the northern highlands of Peru. According to a recent study, its cords appear to have recorded the taxation of 131 community members belonging to six ayllus from the community of San Pedro de Corongo, as detailed in a 1670 document that provides a tax collection register for this locality. This significant discovery confirms that, during part of the colonial period, certain information continued to be recorded in two systems and languages—Andean and Western—at least for a time.

In Tahuantinsuyo, labor and production were organized based on a decimal system, which was applied at different levels of society, from the community level to the regional level. Administrators oversaw groups of 10, 50, 100, 500, 1,000, 5,000, and even 10,000 families. The quipus gathered administrative information, which was relayed up the chain until it reached the rulers. This video briefly explains how this system functioned.

Inca (1400 1532). Paccha en forma de chaquitaclla con urpu y ma�z

Inca (1400 1532). Paccha en forma de chaquitaclla con urpu y ma�z

Land Production

The Tahuantinsuyo is believed to have included an estimated two million hectares of arable land, achieved over the course of centuries through the construction of hydraulic works and farming terraces carved in the mountain sides. Production was ensured by the proper management of labor and technology, as well as ceremonies intended to propitiate the earth’s fertility.

The importance of agricultural labor is reflected in this Inca paccha. Its elongated base in the shape of a chaquitaclla (Andean foot plow) refers to the work of cultivation, with a particular focus on maize harvest, a resource of great economic and ideological significance for the Inca state, symbolized by the corn cob resting on the handle of the plow. The maize grains are used in the preparation of chicha de jora or aqha, a fermented beverage that was ultimately stored and transported in urpus, such as the one represented on a small scale in this piece.

The quero is one of the most representative forms of Inca ceremonial tableware. Mentioned by various chroniclers as one of the gifts the ruler would send to local lords to initiate political negotiations, this wooden vessel became a symbol of potential peaceful assimilation into the Inca imperial apparatus. The Incas also used these vessels to offer drinks to their huacas (sacred places or deities) and ancestors. Queros were usually produced in pairs, made from the wood of the same tree.

Inca (1400 1532). Conopa en forma de alpaca

Inca (1400 1532). Conopa en forma de alpaca

Inca (1400 1532). Conopa en forma de mujer desnuda

Inca (1400 1532). Conopa en forma de mujer desnuda

Chuquibamba Inca (ca. 1470 1532). Chuspa con dise�os de estrellas de ocho puntas y cam�lidos estilizados

Chuquibamba Inca (ca. 1470 1532). Chuspa con dise�os de estrellas de ocho puntas y cam�lidos estilizados

Rituals and Offerings

Rituals were the primary form of direct communication with the forces that gave life to the world. Many of these practices were assimilated by the Incas and continued, with some modifications, even after the Colonial Period. In this section, we display objects that, due to their nature or the energy they transmitted, played active roles in religious life, both in the domestic and the public sphere.

These stone sculptures, known as conopas, were domestic deities that embodied herds and crops. To promote their fertility, the Incas would place llama fat in the cavities of their bodies as part of the ritual. Although their use was prohibited during colonial times, similar objects known as illas continue to be used to this day.

Objects like those displayed here were produced for use in the ceremonies known as Capacocha (qhapaq hucha, "royal obligation"). This event, which typically took place on the volcanoes and snow-capped peaks of the Andes, involved the sacrifice of infants—sons or daughters of the curacas (local leaders)—offered as special gifts to strengthen the relationships between the provinces and the state during times of crisis or celebration. After long pilgrimages, the infants were buried alongside miniature objects shaped like animals and people dressed in clothing representing men and women with Inca features.

Since ancient times, coca has been present in the lives of Andean populations. Used as a stimulant for daily work and as an offering in propitiatory ceremonies, it also serves as a resource in reciprocal relationships. The leaves were carried in bags or chuspas for easier transport, while the lime deposited in caleros or llipteros helped activate the plant's alkaloids.

Inca (1400 1532). Uncu con dise�os cuadriculados

Inca (1400 1532). Uncu con dise�os cuadriculados

Inca (1400 1532). Canipu

Inca (1400 1532). Canipu

Inca Transicional (ca. 1532 1580). Uncu con banda horizontal decorada con dise�os de rombos conc�ntricos

Inca Transicional (ca. 1532 1580). Uncu con banda horizontal decorada con dise�os de rombos conc�ntricos

Identity through Clothing

A range of outfits and ornaments served as markers for the different roles played by certain Inca officials, strategic labor force for the functioning of the State. Below the Sapa Inca and the coya were the soldiers and administrators of different ranks, as well as the mamacona and the aclla. Several of these characters and their attributes were recorded in the illustrated chronicles of the late 16th century, as part of a memory that sought to attest to their existence.

This uncu with a checkered design, described as the attire of the soldiers guarding Inca Atahualpa in Cajamarca, is one of the main emblems of imperial military power. In addition to the garment, weapons such as the macana and huaraca, and ornaments like the tincurpa—a disc-shaped plate that hung from the warrior’s chest—completed the outfit.

The canipu, an insignia attached to a llauto or headband, distinguished imperial officials of various ranks, from inspectors to provincial governors, who were considered “privileged Incas.”

The Inca presence in the Andean region was manifested through elements recognized as symbols of an expanding state. Such is the case with finely crafted textiles (cumbi), produced by specially trained weavers. These fine garments were not only used to dress the Inca nobility but also served as negotiation tools in the process of incorporating other groups into the empire.

Chim� Inca (ca. 1470 1532) Vasija en forma de un pie con sandalia. Vasija en forma de pezu�a de cam�lido

Chim� Inca (ca. 1470 1532) Vasija en forma de un pie con sandalia. Vasija en forma de pezu�a de cam�lido

Landscape, Architecture, and Territory

With its emblematic design and a peculiar way of transforming and integrating into the landscape, Inca architecture contributed to make the State’s presence visible throughout a vast territory. Although the constructions were characterized by a marked simplicity, the elite buildings are easily recognisable by their use of finely polished stone and their trapezoidal forms. From agricultural terraces to royal domains, the Incas adapted their architecture to the topography of the terrain like no other Andean culture. Around 1520, when Tahuantinsuyo reached its greatest extent, a system of State-controlled roads, the Qhapaq Ñan, ran through the Andes and the Altiplano, connecting the different populations of the empire.

The scarce representations of Inca architecture do not necessarily reflect the technological advancements or planning of an expansivestate. However, their forms showcase diagnostic elements of an emblematic style reproduced in various regions. Square-shaped constructions with a single entrance and gable or hip roofs constitute the basic architectural unit, which could be modified or replicated. The presence of human or animal figures in these vessels, which do not maintain the same scale as the buildings, suggests that these pieces were not models or replicas.

The Qhapaq Ñan allowed for the interconnection of various provinces and their administrative centers with Cuzco. Composed of a series of longitudinal and transversal roads, this system served to mobilize resources and information carried by chasquis (messengers) in quipus, as well as to transport military troops and the Inca elite from one place to another. Today, many sections of these roads are still in operation, used by various communities as well as tourists.

Inca Provincial (ca. 1470 1532). Paccha que representa a un cuenco con cinco conchas de Spondylus

Inca Provincial (ca. 1470 1532). Paccha que representa a un cuenco con cinco conchas de Spondylus

Spondylus

From very early times, the Spondylus shell was highly prized by elites, eventually becoming as important as silver or gold. This mollusk, found in warm equatorial waters, was used to make ornaments and as offerings. The Incas controlled their production and circulation, distributing the products via the road network.

Inca (1400 1532). Plato con mango en forma de cabeza de ave y dise�os geom�tricos. Plato con mango en forma de cabeza de cam�lido y dise�os geom�tricos

Inca (1400 1532). Plato con mango en forma de cabeza de ave y dise�os geom�tricos. Plato con mango en forma de cabeza de cam�lido y dise�os geom�tricos

Art and Geometry

The visual language of the Incas can be distinguished by a break from earlier Andean traditions. While the majority of representations have been classified as geometric or abstract—possibly inspired by the textiles’ structure—we also find distinctly simple figurative images, as well as combinations of color patterns. For the Incas, however, the process of creating these objects and the materials used were more important than surface appearance, because it was the object’s essence that mattered above all in their worldview.

A tuning point

From the moment Francisco Pizarro and his troops made contact with Tahuantinsuyo, violence laid the foundations for a new order in the Andes. The initial milestone of this process was the capture and execution of the Inca Atahualpa in 1532. However, dismantling that empire not only required the involvement of thousands of natives; it also demanded the negotiation of power with certain Indigenous groups. In turn, the name Tahuantinsuyo was replaced by that of Peru, a term that would come to signify something very different as colonial power consolidated. Even the memory of pre-Hispanic times was transformed to fit the needs of a Christianized society and the imposition of Western artistic languages. This sparked a lasting tension between rupture and continuity with the past.

An�nimo. Quero con representaci�n del brindis entre el Inca y el rey Colla, ca. 1700 1800

An�nimo. Quero con representaci�n del brindis entre el Inca y el rey Colla, ca. 1700 1800

Certain early colonial queros feature geometric decorations typical of the Inca visual language. However, the predominant trend ran in the opposite direction, with vases that began to incorporate figurative motifs that were sometimes mixed with incised designs or tocapu. The emergence of this new visual repertoire was cemented by the use of Mopa Mopa resin, which was dyed and inlaid on the surface of the wooden cups. While Colonial authorities organized the systematic destruction of these types of objects on numerous occasions, this did not keep people from using them. In fact, queros became the most widely used visual support for preserving a memory of the Incas, though often adapted to a Christian scale of values.

Diego de Villanueva y Juan Bernab� Palomino. Sucesi�n de los incas y reyes del Per�, 1748

Diego de Villanueva y Juan Bernab� Palomino. Sucesi�n de los incas y reyes del Per�, 1748

The Incas, Kings of Peru

The Spanish conquerors not only used the term "Peru" to refer to the former domains of Tahuantinsuyo. They also imagined the Incas as “kings” who had ceded sovereignty over those territories to new monarchs, the kings of Spain. However, this image of Peru as a “kingdom” not only supported colonial power; it was also used by local elites to claim a level of autonomy similar to that enjoyed by the European kingdoms within the Spanish crown. In turn, this rewriting of the past granted significant symbolic power to the colonial Indigenous nobility, especially when they also defended their full adherence to Christianity. The landscape only changed dramatically in 1781, when Túpac Amaru II, who proclaimed himself as Inca, was defeated after leading the largest uprising against colonial power.

The fiction of a legitimate continuity between the past preceding the Conquista and Spanish rule found one of its most emphatic visual formulations around 1725. At that time, the clergyman Alonso de Cueva devised in Lima a composition that showed the succession of rulers of the “kingdom of Peru”: after the Incas, the series continues immediately with the Spanish monarchs, which creates the fiction of an almost natural continuity. This image became so recurrent in the Peruvian viceroyalty that the Spanish scientists Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa included it, with several changes, in their Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional, published in Madrid in 1740.

La conquista como un pacto

In the late seventeenth century, the image of the Incas became a key symbol for different sectors of viceregal society. This was achieved through a shrewd rewriting of the past that legitimized the rule of the Spanish Crown, as well as the aspirations of local societies. Thanks to the memory of the “Inca kings,” it became possible to imagine Peru as a kingdom, and to claim a greater autonomy for its elites, not unlike what was happening in the European kingdoms of the Spanish Empire. This gave a certain symbolic power to the colonial Incan nobility, who were also bolstered by the privileges granted to them by King Charles II.

This work is exceptional for its ambiguity. At first glance, it seems to depict the miraculous appearance of the apostle Santiago around 1535, when—according to a pious tradition—he intervened to defend the Spanish troops besieged in Cuzco by the forces of Manco Inca. However, upon closer inspection, the foreground scene is actually a representation of the Battle of Clavijo: Santiago is shown defeating the Moors, in line with the legendary accounts that tell of the apostle fighting alongside the troops of the King of Asturias in the year 844. Additionally, the images in the background of the composition seem to portray the meeting between Pizarro and the Inca Atahualpa in Cajamarca, along with what appears to be a very subtle critique of the Conquest. On the left side of the composition, two Indigenous figures seem to offer gold on a tray as food for a horse and its rider.

Manuela Tupa Amaro

This work is an exceptional testimony to the fate that befell the colonial Indigenous elites. It was painted during the legal battle between Diego Betancur, the son of the woman portrayed, and José Gabriel Condorcanqui. Both were claiming the Marquisate of Oropesa, a title that recognized the closest descent from the imperial Inca lineage. Under the name Túpac Amaru II, Condorcanqui would go on to lead the largest rebellion against the colonial order in 1781. After crushing the uprising, the colonial authorities also sought to destroy the key role that the memory of the Incas had played in the visual culture of the region. It was probably at that time that the decision was made to cover Manuela's portrait by painting over it with a representation of the Lord of the Earthquakes. Preserved in this way from destruction, the work was rediscovered in the 1970s when Peruvian historian Francisco Stastny ordered the covering image to be removed.

Marcos Chillitupa Chávez

Genealogía de los incas, 1837

Painted just over a decade after the end of Spanish rule, this folding screen condenses different stages of art in Peru: it evokes the pre-Columbian past in the form of a genealogy of the Incas. But its composition is based on a colonial image, which shows the Incas and then, as a legitimate succession, Spanish rule, symbolized by the kings who ruled during the colonial period. In this case, however, the Hispanic monarchs have been eliminated to close the sequence with the “Liberator of Peru,” probably Simón Bolívar. Added to this detail is the joint presence of the coats of arms of Cuzco and the Peruvian State, placed there to exalt the Independence process, equating the old empire of the Incas with the new republic.

Amid the diversity of colonial societies, finely crafted clothing uncus and acsos could indicate that they belonged to a noble Inca lineage. This is why many of these garments were passed down from parents to children, serving as symbols that legitimized a family's privileges. Such is the case with this female outfit. Created in the early decades of the colonial period, the acso features butterfly motifs that, despite their figurative nature, immediately evoke the geometric logic of Inca imperial art. The garment complements an exceptionally designed lliclla, making it difficult to determine whether both textiles are from the same era or if the smaller one was made centuries later.