Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed

Philip Larratt-Smith

More than any other artist of the twentieth century, Louise Bourgeois (1911 – 2010) has produced a body of work that consistently and profoundly engages with psychoanalytic theory and practice. While the Surrealists may have tapped into dream imagery and the Abstract Expressionists linked their gestural spontaneity to the unconscious, Bourgeois’s art offers unique insight into the linkage between the creative process and its cathartic function. Taken as a whole, her art and writings represent an original contribution to the psychoanalytic inquiry into symbol formation, the unconscious, the talking cure, the family romance, maternal and paternal identifications, and the fragmented body. Through her exploration of materials, forms, and sculptural processes Bourgeois finds a plastic equivalent for the psychological states and mechanisms of fear, ambivalence, compulsion, guilt, aggression, and withdrawal.

Bourgeois considered the act of making art as her “form of psychoanalysis”, and believed that through it she had direct access to the unconscious. In her view the artist, powerless in everyday life, possesses the gift of sublimation and becomes omnipotent during the creative act. Yet the artist is also a tormented, Sisyphean figure condemned endlessly to repeat the trauma through artistic production. Hence the very process of making art is a form of exorcism, a means of relieving tension and aggression. It is also, like psychoanalysis, a source of self-knowledge. Or as Bourgeois has often said, “Art is a guaranty of sanity”.

Bourgeois’s career as an artist in New York began with solo exhibitions of paintings in 1945 and 1947 followed by three exhibitions of her wood sculptures and environmental installations in 1949, 1950, and 1953. She would not have another solo show of new work again until 1964, when she presented an innovative body of abstract sculpture at the famous Stable Gallery in New York. These seminal forms in plaster, rubber, and latex were included in Lucy Lippard’s epochal exhibition “Eccentric Abstraction” at the Fischbach Gallery in New York in 1966, along with Bruce Nauman and Eva Hesse. Yet where Nauman and Hesse arrived at post minimalist forms by way of philosophy and conceptualism, Bourgeois’s evolution was informed and inspired by her own experience of psychoanalysis.

Bourgeois began psychoanalysis with Dr. Leonard Cammer in 1951, the year her father died. In 1952 he switched to the analyst Henry Lowenfeld. Born in Berlin in 1900, a former disciple of Freud in Vienna, Lowenfeld moved to New York in the same year as Bourgeois (1938), and there became an important member of the New York Psychoanalytic Society, publishing widely. Bourgeois would remain in therapy with Lowenfeld until the early 1980s. During a period of withdrawal and depression in the 1950s, Bourgeois not only underwent analysis but also steeped herself in psychoanalytic literature, from Sigmund Freud to Erik Erikson, Anna Freud, Melanie Klein, Heinz Kohut, Susanne Langer, Otto Rank, Wilhelm Reich, and Wilhelm Stekel.

Prior to her retrospective at the Tate Modern in 2007, two boxes of writings were discovered in Bourgeois’s home, followed by two more in 2010. These writings, which have never been published, serve to augment and enrich our understanding of Bourgeois’s artistic development and fill in the gap in her otherwise copious diaries and process notes. In literary quality and historical importance they may be compared to the journals of Eugène Delacroix and the letters of Vincent van Gogh. They constitute a parallel body of work expressing her struggle to come to terms with her psychic life and the legacy of her past. In these documents Bourgeois records and analyses her dreams, emotions, and anxieties, and in particular her conflicted feelings about being simultaneously a creative artist and a mother and wife. The linkage between feeling, thought, and sculptural process becomes clearly delineated. At the same time these writings, like her sculptural works, critique psychoanalytic theory in its relationship to female sexuality and identity. These writings illuminate her transition from the figurative works of her Abstract Expressionist period to the abstract pieces that ushered in the Post minimalist tendency, and articulate how her relationship to psychoanalysis remained active until the end of her life.

List of works

The works are organized in the order of the visit. Measures are noted as follows: height x width x length. Except when stated, works are courtesy of the Louise Bourgeois Trust.

Maman, 1999

Bronze, stainless steel and marble. 927.1 x 891.5 x 1023.6 cm

Private Coll., courtesy Cheim & Read

Gallery 1

Bourgeois’ spiders are an homage to her mother. They symbolize protection, nurturing, and reconciliation. Spider (1997) is one of Bourgeois’ series of Cells, installations made in the 1990s that explore memory and desire through the five senses. Here the spider’s web is given an architectural form in the cage that encloses objects from Bourgeois’ past. Bourgeois was obsessed with her past and yet, wished to be liberated from it in order to experience the present. Thus, the cage can be viewed as both refuge and trap (hence the animal bones).

Inside the cage, Bourgeois placed the glass cupping jars, which as an adolescent she placed on her mother’s back when the latter was sick with Spanish flu. The tapestries refer to the family atelier in which the young Bourgeois drew in the feet that were missing from tapestries that needed to be rewoven. In one fragment of tapestry, the genitals of the putti have been cut out, as her mother had done to appease their puritanical American clients. Her mother replaced the holes with flowers, and kept a collection of cutout fragments of male genitalia. The hanging forms are aides-memoire consisting of perfume, a photograph, a locket, and a cloth, which serve to conjure the past.

While under analysis, the patient sits in the chair and attempts to give a form to the inchoate mass of sensory perceptions, memories, and emotions Psychoanalysis is the process of tracing the etiology of neuroses by excavating one’s past.

The suite of engravings He Disappeared Into Complete Silence (1947) consists of nine plates pairing terse, fabulist texts with vertical architectural forms that, in their isolation from one another, parallel the contemporaneous Personnages and deal with the inability of people to communicate with each other.

1. Spider, 1997

Steel, tapestry, wood, glass, fabric, rubber, silver, gold and bone. 449.6 x 665.5 x 518.2 cm.

Private Coll., Courtesy Cheim & Read

2. He Disappeared into Complete Silence, 1947

Suite of nine engravings with text. Each: 25.4 x 35.6 cm

Gallery 2

The monolithic Personnages were created between 1946 and 1953, and were exhibited in three successive exhibitions at Peridot Gallery in New York (1949, 1950, and 1953). Originally carved in wood, they were later cast in bronze. Conceived as an installation, these fragile, top-heavy works had to be bolted directly into the floor or else they would fall over. Bourgeois wanted the viewer to be able to walk among these works, as if in a social environment. Bourgeois thought of these vertical forms as substitutes for the people she had left behind in France when she moved to New York City in 1938 (or in some cases as fetishistic surrogates for the people she loved the most, such as her son Jean-Louis). Thus, as the term Personnage implies, they are sculptural representations of the human figure. By making these surrogates portables Bourgeois ensured that they were dependent on and inseparable from her, which expresses in reverse her fear of abandonment. Dagger Child (1950) communicates the defensiveness and vulnerability that also characterizes the later fabric work Knife Woman (2002), wherein a woman or child appropriates the aggression associated with the phallus. Untitled (1963) exemplifies a later development within the same body of work, involving the stacking of segmented elements around a central vertical axis – an action that has its therapeutic implications, for it was in 1951 that the death of her father pushed Bourgeois into a full-blown depression and into analysis with Dr. Henry Lowenfeld. The need to create these assemblages is rooted in a powerful fear of fragmentation and psychic disintegration, pointing as well to the deconstruction and reconstruction the patient undergoes in analysis. The physical action of carving and separating were outlets for Bourgeois’s fear, hostility, and aggression

Bourgeois’ most intense period in analysis took place between 1952 and 1967, during which time she followed the classical Freudian formula of four one-hour sessions per week with Dr. Lowenfeld. Psychoanalysis endowed her with a more conscious understanding of the meanings and the emotional needs behind her Personnages, just as it informed the works, which she made during the late 1950s and early 60s and exhibited at the Stable Gallery in New York City in 1964, after a hiatus of eleven years.

Consisting of seemingly amorphous forms in plaster and latex with raw exteriors and intricate interiors, works such as Lair (1963), Fée Couturière (1963), and Amoeba (1963-65) resemble shells or animal cocoons, structures for hiding and protecting herself. These works give way to poured plastic and resin formations such as Soft Landscape (1967), End of Softness (1967), and Unconscious Landscape (1967-68) that suggest a metamorphosis frozen in time. Out of these soft landscapes emerge protuberances and coagulations that stretch and sometimes penetrate the surface like a discharge of excitations. Other works from this period, such as Janus Fleuri (1968), Fillette (1969), and Le Trani Episode (1971) became more sexually explicit: part objects and hybridized forms that merge male and female in an uncanny and ambivalent fusion.

Like the return of the repressed, Bourgeois’ themes reappear throughout her career, and though her body of work can be read chronologically, the evolution of her sculptural forms is less like a linear narrative and more like one of her favorite form: the spiral. Hence the works in this room bring together discrete bodies of work made in different media, processes, and scales, and yet they reflect the singular pathology that unites her oeuvre as a whole.

As a defense against her deep-seated fear of separation and abandonment, in the 1990s Bourgeois began to incorporate fabric materials from her life, such as towels, linens, bed sheets, and clothes into her work. These objects contain and embody memories; they are markers of time, of people and places she has known. The impulse to use these kinds of material derives in part from a characteristically ambivalent desire to dispose of her past and at the same time by incorporating them into her art, she assures that they will survive. In contrast to such aggressive actions as cutting and carving, joining through the process of sewing is a symbolic action that conveys the desire for reparation and reconciliation. This process is also an act of identification that places Bourgeois in the position of her mother, who was a tapestry restorer in the family business.

Bourgeois began using the device of hanging as a formal strategy from the 1960s onwards, from Fée Couturière (1963) and Hanging Janus with Jacket (1968) to Arch of Hysteria (1993) and Single I (1996). To hang a sculpture is to emphasize its fragility and vulnerability. No position is fixed or final, as the hanging forms are able to spin and turn. The form traced in the air by these motions is the spiral, with its double movement of turning inwards (signifying retreat and withdrawal) and outwards (signifying acceptance, an opening up to life). As Bourgeois stated: “Horizontality is a desire to give up, to sleep. Verticality is an attempt to escape. Hanging and floating are states of ambivalence and doubt”.3. Dagger Child, 1947-1949

Bronze, paint and stainless steel. 192.1 x 30.5 x 30.5 cm

4. St. Sebastienne, 1947

Watercolor and pencil on paper. 27.9 x 18.4 cm

Private Coll., New York

5. Untitled, 1953

Bronze. 150.5 x 21.6 x 21.6 cm

6. Forêt (Night Garden), 1953

Bronze, brown and black patina and white paint. 92.1 x 47 x 36.8 cm

7. Labyrinthine Tower, 1962

Bronze. 45.7 x 30.5 x 26.7 cm

8. Untitled, 1950

Ink on blue paper. 21.6 x 10.2 cm

9. Lair, 1963

Latex. 24.1 x 42.5 x 36.5 cm

10. Clutching, 1962

Plaster. 30.5 x 33 x 30.5 cm

11. Torso, Self Portrait, 1963-1964

Bronze, painted white, wall piece. 62.9 x 40.6 x 20 cm

12. Torsade, 1962

Bronze. 20.3 x 20.3 x 15.2 cm

13. Rondeau for L, 1963

Bronze, greenish black patina. 27.9 x 27.9 x 26.7 cm

14. Lair, 1962

Bronze, painted white. 55.9 x 55.9 x 55.9 cm

15. Untitled (double sided), c. 1960

Recto: Ink and pencil on paper. Verso: Pencil on paper. 34.3 x 25.4 cm

16. Soft Landscape, 1967

Aluminum. 17.1 x 50.2 x 43.8 cm

17. Le Regard, 1966

Latex and cloth. 12.7 x 39.4 x 36.8 cm

18. Untitled, 1953

Ink on paper. 29.2 x 18.4 cm

19. Amoeba, 1963-1965

Bronze, painted white, wall piece. 95.3 x 72.4 x 33.7 cm

20. Uncounscious Landscape, 1967-1968

Bronze, black and polished patina. 30.5 x 55.9 x 61 cm

21. Dans La Tourmente, 1950

Pencil and ink on paper. 27.9 x 21.6 cm

22. Germinal, 1967

Marble. 14 x 18.7 x 15.9 cm

23. Untitled, 1960

Red ink on paper. 29.8 x 22.9 cm

24. The Fingers, 1968

Latex and plaster. 8.3 x 44.5 x 22.9 cm

25. The Loved Hand, 1967

Bronze. 22.9 x 31.8 x 20.3 cm

26. End of Softness, 1967

Bronze, gold patina. 17.8 x 52.1 x 38.7 cm.

Private Coll., New York

27. Fillete (Sweeter Version), 1968-1999

Pigmented urethane rubber, hanging piece. 59.7 x 26.7 x 19.7 cm

28. Portrait of Robert, 1969.

Bronze, painted white. 33 x 31.8 x 25.4 cm

29. Medical Horizontal (double sided), 1998

Colored inks, pencil and whiteout on paper. 22.9 x 30.5 cm

Private Coll., New York

30. Untitled, 1942

Pencil on paper. 22.9 x 21.6 cm.

Private Coll., New York

31. Harmless Woman, 1969

Bronze, gold patina. 28.3 x 11.4 x 11.4 cm

32. Rabbit, 1970

Bronze, wall piece. 58.4 x 28.9 x 14.9 cm

33. Loose sheet of writing, c. 1959

22.2 x 13.7 cm

Louise Bourgeois Archive, New York

34. Le Trani Episode, 1971

Bronze, dark and polished patina. 41.9 x 58.7 x 59.1 cm

35. Janus Fleuri, 196

Bronce, pátina dorada, pieza colgante. 25,7 x 31,8 x 21,3 cm

36. Hanging Janus with Jacket, 1968

Bronze, dark and polished patina, hanging piece. 27 x 52.4 x 16.2 cm

37. Untitled, 2007

Fabric and thread. 33 x 47 x 30.5 cm.

Stainless steel, glass and wood vitrine: 177.8 x 76.2 x 60.9 cm

38. Couple, 2001

Fabric, hanging piece. 48.3 x 15.2 x 16.5 cm.

Stainless steel, glass and wood vitrine: 193 x 60.9x 60.9 cm

39. Rejection, 2001

Fabric, steel and lead. 63.5 x 33 x 30.5 cm.

Aluminum and glass vitrine: 185.4 x 68.5 x 68.5 cm

Coll. John Cheim, New York

40. Untitled, c. 1970 -Sin título-

Ovalo: pintura sobre panel. 119,4 x 149,9 cm

Col, privada, Nueva York

41. Couple I, 1996

Fabric, hanging piece. 203.2 x 68.6 x 71.1 cm

42. Knife figure, 2002

Fabric, steel and wood. 22.2 x 76.2 x 19.1 cm.

Stainless steel, glass and wood vitrine: 177.8 x 96.5 x 45.7 cm

43. Seven in Bed, 2001

Fabric, steel and wood. 22.2 x 76.2 x 19.1 cm.

Stainless steel, glass and wood vitrine: 177.8 x 96.5 x 45.7 cm

44. Untitled, 1999

Fabric, wood and metal. 64.8 x 20.3 x 30.5 cm.

Stainless steel, glass and wood vitrine: 188 x 60.9 x 60.9 cm

45. Fée Couturière, 1963

Bronze, painted white, hanging piece. 100.3 x 57.2 x 57.2 cm

46. Arch of Hysteria, 1993

Bronze, polished patina, hanging piece. 83.8 x 101.6 x 58.4 cm

Bronze, polished patina, hanging piece. 83.8 x 101.6 x 58.4 cm

47. Untitled (I Have Been to Hell and Back), 1996

Embroidered handkerchief. 49.5 x 45.7 cm.

Private Coll., New York

48. Single I, 1996

Fabric, hanging piece. 203.2 x 68.6 x 71.1 cm

49. Claustrophobia and Omnipotence, 2007

Pencil on paper, suite of four

Each: 75.6 x 57.2 cm

Gallery 3

Rather than be dependent on architectural spaces, Bourgeois began creating her own architecture in a series called Cells that contain objects both belonging to the artist and made by her. Red Room (Parents) is a dramatic staging of the psychoanalytic concept of the primal scene, where the child enters into the bedroom witnesses her parents in coitus and tries to make sense of what he perceives. As Freud noted, the primal scene is often a fantasy. For Bourgeois, red is the color of violence, passion, blood, and emotional intensity.

The Femme Maison (1946-47) paintings touch upon the problem of identity for women. Here, the heads of nude female figures have been replaced by architectural forms, resulting in a symbolic condensation of the conflict between domestic and sexual roles. For Bourgeois architecture symbolizes the social world that attempts to define the individual, in contrast to the inner world of emotion. The tension between figure and architecture mirrors the dichotomy between mind and body. Bourgeois suffered from acute agoraphobia, and often withdrew into her house for protection. Yet, as Bourgeois wrote, “the security of the lair can also become a trap.”

The Destruction of the Father (1974) is the culmination of the works Bourgeois made in the 1960s and early 70s, synthesizing the cave-like structure of the lairs, the primordial forms of the soft landscapes, and the more explicit sexual attributes of works such as Sleep II (1967). According to Bourgeois’ account, she was reenacting a childhood revenge fantasy of revolt against her father who gloats and brags at the dinner table and whom, in exasperation, she dismembers and devours. In Bourgeois’ visual realm, each thing contains the form of appearance of its opposite. The pendulous breast-like forms set within a recessed interior like an orifice express the wish to return to the womb and be reunited with the lost mother. More, to be “eaten” by the mother or to “eat” the father is an act with strong sexual and incestuous overtones. The tension of all of Bourgeois’ work resides in the unresolved and irresolvable contradictions between binary oppositions– male and female, conscious and unconscious, past and present, active and passive, inside and outside, pleasure and unpleasure.

50. The Feeding, 2007

Gouache on paper. 59.7 x 45.7 cm.

Courtesy Cheim & Read and Hauser & Wirth

51. Red Room (Parents), 1994

Mixed media. 247.7 x 426.7 x 424.4 cm

Coll. Ursula Hauser, Switzerland

52. Femme Maison, 1946-1947

Oil and ink on linen. 91.4 x 35.6 cm

53. Femme Maison, 1946-1947

Oil and ink on linen. 91.4 x 35.6 cm

54. Sleep II, 1967

Marble. 59.4 x 76.8 x 60.3 cm

Two wooden timbers, each: 27.9 x 83.8 x 35.5 cm

68. The Destruction Of The Father, 1974

Plaster, latex, wood, fabric and red light. 237.8 x 362.3 x 248.6 cm

Gallery 4

Throughout her life, Bourgeois suffered from an intense fear of abandonment. The fabric text piece I Am Afraid (2009) deftly links three images – “empty stomach/ empty house/ empty bottles” – in a condensed metaphor that expresses this fear by stringing together body and architecture, container and contained. Le Défi II (1992) speaks to the need for restraint and self-control and to Bourgeois’s awareness that human relationships are fragile. The “challenge” of which the French title speaks is the challenge to resist the urge to give way to aggression or hostility, which may unsettle the precariously balanced cabinet, with its carefully placed and easily broken glass elements. These elements may also be read as symbols of the internal organs, and the entire cabinet as another architectural metaphor for the human body. Their transparency signifies a world without secrets, Bourgeois’ compulsion to confess everything out of a desire for forgiveness.

Couple IV (1996) presents a man and a woman in black fabric in the sexual act placed within a 19th century Victorian vitrine. The female figure is wearing a prosthesis, suggesting that she is incomplete, perhaps wounded, as are so many of Bourgeois’ representations of women. Despite her handicap, she is defined by her relationship to him and fearful of being separated from this desire. Conscious and Unconscious (2008) recapitulates in fabric elements the stacked forms of her earlier segmented Personnages, just as the more organic form in blue rubber recalls the soft forms of the 1960s. The five spools symbolize Bourgeois’ two families of five (the family into which she was born and the family she had with her husband Robert Goldwater), and evoke the Bourgeois family tapestry atelier. The thin threads express both the tenuous connection of the five family members and the strands of memory embedded in the unconscious.

This room was conceived in hommage to one of Bourgeois’ favorite phrases, “pink days” (good days) and “blue days” (bad days). If the preceding room is more somber and brooding in tone, dwelling upon the difficulty and fragility of human relationships, this room is lighter and more delicate. In Nature Study (1984-2002) animal and human, male and female sexual parts are fused in an uncanny hybrid. The male genital is protected by the multiple breasts, just as Louise felt she was protecting her husband and three sons. Mamelles (1991) consists of a cluster of breasts, part objects that form a bodily landscape and signifies the nourishing mother. The red gouaches made late in Bourgeois’ career show her honing in on the most universal events and cycles of human life: birth, copulation, insemination, gestation, family and death. In The Family (2008) distinct moments – penetration, pregnancy, and motherhood – are collapsed into each gouache in this grid of nine.

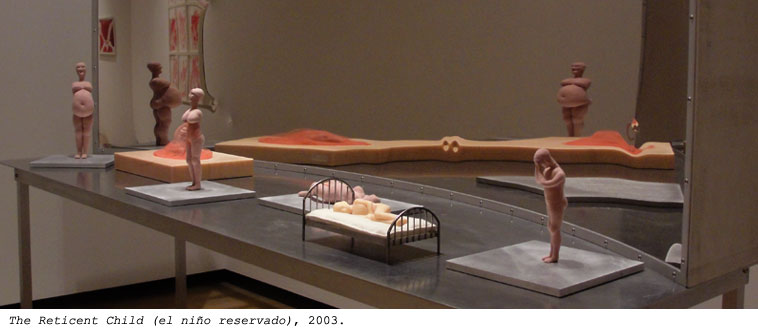

The Reticent Child (2004) relates the stages of a relationship between a mother and a son. In this work, the child is late in being born, a circumstance that will affect his entire relationship to the world. The concave mirror behind the fabric and marble figures gives back distorted images of this tableau, implying that memory, like desire, is shaped by emotion and structured in a non-linear fashion. As always in Bourgeois’ work, each image is properly dialectical and involves its opposite. Hence the iconography of nurturing and breastfeeding not only expresses Bourgeois’ concern with her role as mother but also shows her in need for a nurturing mother (hence “Maman” as if calling out for her mother) as she became more frail and dependent with age. Thus, these raw images of birth, the coming into the world and her connection to her mother, foretell the inevitability and proximity of death.

56. Conscious and Unconscious, 2008

Fabric, rubber, thread and stainless steel. 175.3 x 94 x 47 cm

White oak, glass and stainless steel vitrine: 224.8 x 167.6 x 94 cm

57. I am Afraid, 2009

Woven fabric. 110.5 x 182.9 cm

58. Le Défi II, 1992

Painted wood, glass and electric lights. 200.7 x 179.7 x 59.7 cm

59. Couple IV, 1997

Fabric, leather, stainless steel and plastic. 50.8 x 165.1 x 77.5 cm

Wood and glass Victorian vitrine: 182.9 x 208.3 x 109.2 cm

61. Maman, 2009

Gouache and pencil on paper. 91.4 x 121.6 cm

62. The Feeding, 2007

Gouache on paper. 59.7 x 45.7 cm

Courtesy Cheim & Read and Hauser & Wirth

63. The Good Mother, 2007

Gouache on paper. 37.1 x 27.9 cm

64. The Feeding, 2007

Gouache on paper. 60 x 45.7 cm

Coll. Museum of Modern Art, New York

65. Maman, 2008

Gouache on paper. 45.7 x 61 cm

66. Nature Study, 1984-2002

Blue rubber. 76.2 x 48.3 x 38.1 cm.

Stainless steel base: 104.1 x 55.2 x 55.2 cm

67. The Family, 2008

Gouache on paper, suite of nine. Each: 36.8 x 27.9 cm

68. The Reticent Child, 2003

Fabric, marble, stainless steel and aluminum: six elements. 182.9 x 284.5 x 91.4 cm

69. Mamelles, 1991

Pigmented urethane rubber, wall relief. 48.3 x 304.8 x 48.3 cm

Proa Library

Bourgeois drew consistently throughout her career, creating a unique corpus of drawings that balances formal inventiveness and psychological specificity. The artist maintained that, unlike sculpture, drawing did not result in an exorcism of past trauma because it did not involve the body. Yet the drawings offer an intimate record of the shuttling of her mind from past to present, passive to active, unconscious to conscious. In some works figurative elements predominate, while in others - such as Spiral (2009), which resumes a favorite form of the artist’s in the medium of red gouache, which she favored in her last years -abstraction and geometry come to the fore-. Abstraction usually indicates that the unconscious mind is in the ascendant, whereas the figure or fragments thereof are traces of a problem, which Bourgeois is consciously addressing. The singularity of her line is matched by her idiosyncratic manner of writing. In Je Les Protégerai (2002) she repeats the refrain "calme toi, petite Lison" with subtle variations. In Here and Now (1988) Bourgeois engages in a dialogue with herself.

This selection of facsimiles of the psychoanalytic writings of Bourgeois shows how closely her writerly practice mirrors her drawings. The writings were discovered in 2010 by Bourgeois’ long-time assistant Jerry Gorovoy at her Chelsea home, and immeasurably augment and enrich our understanding of the artist’s life and work. They form the kernel of this exhibition and of the accompanying publication.

The form of the writings often sheds light on her motivations and the formation of her symbols. In many of the writings, drawing elements are interspersed with text. In others, the image structures the flow of the text. Sometimes the text is organized in tightly wound coils, sometimes in lists that resemble her stacked sculptural forms.

Like her drawings, these writings, which were produced under the pressure of a psychological and emotional need rather than as a literary endeavor, offer us an intimate look at the movements of her restless mind. These facsimiles are complemented here by a selection of relevant photographs from Bourgeois' life.

70. Spiral, 2009

Gouache on paper. 59.7 x 45.7 cm

71. Je les Protégerai, 2002

Ink and pencil on paper. 24.1 x 20.3 cm

72. Art is a Guaranty of Sanity, 2000

Pencil on pink paper. 27.9 x 21.6 cm

Coll. Museum of Modern Art, New York

73. Here and Now, 1988

Chalk on blue paper. 73.7 x 58.4 cm

74. Untitled (double sided), 1995

Recto: Ink and pencil on paper. Verso: Pencil on paper

30.5 x 22.9 cm

75. The Punishment of the Dagger Child (double sided), 1998

Ink and gouache on paper. 29.2 x 22.9 cm

76. Untitled, 2002

Ink and pencil on music paper. 29.8 x 22.9 cm

77. The Beating of the Heart (double sided), 2006

Recto: Watercolor and pencil on embossed paper

Verso: Watercolor on paper

76.2 x 53.3 cm

78. Unconscious Compulsive Thoughts, 1998

Pencil on paper. 22.9 x 29.5 cm

79. Spiral Woman, 1984

Bronze, hanging piece, with slate disc

Bronze: 48.3 x 10.2 x 14 cm.